INTRODUCTION

The wide range of potential applications of nanomaterials has become a central focus of modern research. This growing interest stems from nanotechnology’s unique ability to alter material properties simply by changing their size. Nanotechnology, as defined by the U.S. National Nanotechnology Initiative, involves manipulating matter at dimensions between 1 and 100 nanometers [1][2]. The development of nanotechnology draws upon multiple scientific disciplines, including interface science, biology, molecular science, semiconductor physics, and microfabrication technologies [3][4].

Nanotechnology enables the creation of novel materials and offers vast potential in diverse sectors such as energy production, electronics, biomaterials, and environmental applications [5][6]. Although nanoscience has the transformative potential to impact various academic and industrial domains, its usefulness is already well established across numerous fields [7]. In recent years, nanotechnology has shown remarkable promise in areas like healthcare, agriculture, nutrition, and medicine [8].

A major area of focus in nanotechnology is the synthesis of nanoparticles with specific chemical compositions, shapes, sizes, and tailored properties. Among these, noble metal nanoparticles—especially palladium nanoparticles (PdNPs)—have attracted significant attention due to increasing demand for eco-friendly synthesis methods [9][10]. Palladium (chemical symbol Pd), with atomic number 46, is a rare silvery-white metal discovered in 1803 by the English chemist William Hyde Wollaston [11]. It was named after the asteroid Pallas, discovered a year earlier. While sharing many properties with other platinum group metals, palladium stands out for its lowest melting point and density within the group.

Natural palladium sources are limited to a few countries, and recycling serves as a crucial secondary supply. In 2020, approximately 96,000 kilograms of palladium were recycled, primarily from used jewelry and automotive catalytic converters [12]. However, due to supply constraints and increasing demand, palladium prices have surged in recent years [13].

Crystallinity plays a key role in determining the final morphology and structure of palladium nanoparticle seeds. The physicochemical properties of PdNPs, especially when organized into nanoscale clusters, are highly dependent on their size and structural configuration. Green synthesis using biological systems—such as bacteria, fungi, and plant extracts—has opened up new avenues for energy-related applications. These include catalytic degradation, cancer therapy, drug delivery, chemical and biosensing, and hydrogen storage and sensing [14][15].

Today, one of the major uses of palladium is in automotive catalytic converters. Palladium helps convert harmful gases like carbon monoxide and nitrous oxide in vehicle emissions into less harmful compounds such as carbon dioxide and nitrogen. Noble metals like palladium remove up to 90% of these pollutants using auto-catalyst systems. In 1993, the combustion industry introduced palladium-based catalytic converters as alternatives to traditional platinum-rhodium systems [16]. However, palladium initially faced limitations due to its lower stability and higher susceptibility to poisoning from contaminants in vehicle exhaust gases [17].

PdNPs possess a range of remarkable physiochemical properties, including high thermal stability, good processability, strong photostability, favorable surface charge, optical absorption, and cost-effectiveness [18][19]. Several methods exist to synthesize palladium nanoparticles in various shapes and sizes. Their biocompatibility can be enhanced by coating them with biopolymers or chemical modifiers [20].

Palladium nanoparticles are widely used in fuel cells, sensors, hydrogen storage, sensing applications, and organic synthesis reactions. In the pharmaceutical industry, PdNPs play a vital role as catalysts in carbon–carbon bond formation and oxidation reactions [21]. Their strong affinity for hydrogen and catalytic activity further elevate their relevance in advanced technologies.

Green synthesis of PdNPs using plant extracts has been explored extensively. For instance, Kanchana et al. (2010) synthesized PdNPs using Solanum trilobatum, while Catharanthus roseus leaf extract was used to reduce palladium ions via phenolic compounds, producing nanoparticles effective in dye degradation. Additionally, commercial beverages like coffee and tea have been employed as reducing agents to synthesize PdNPs at room temperature using palladium chloride as a precursor. The resulting cubic-symmetric PdNPs had sizes ranging from 20 to 60 nm [22][23][24].

Despite their potential, palladium nanoparticles remain relatively underexplored in medical applications. For example, spherical PdNPs synthesized using white tea extract ranged from 6 to 18 nm in size. These nanoparticles showed strong antibacterial activity against Staphylococcus epidermidis and Escherichia coli, along with significant DPPH radical scavenging capacity [25]. Another green synthesis involved using protein-rich Glycine max (soybean) leaf extract. UV-visible spectroscopy revealed nanoparticle formation within a minute, showing a characteristic absorption peak at 420 nm, indicating the presence of Pd ions. The synthesized nanoparticles had an average size of approximately 15 nm [26].

Properties of Palladium Nanoparticles

Nanomaterials possess structural characteristics that lie between those of individual atoms and bulk materials. Although most micro-structured materials resemble their conventional counterparts, nanoscale substances exhibit distinct behaviors compared to atoms or bulk matter [27, 28]. Due to their extremely small size, nanomaterials have a high surface-to-volume ratio, meaning a large fraction of their atoms are located at the surface. This leads to pronounced “surface-dependent” properties in nanomaterials [29, 30]. When the particle dimensions are comparable to their diameter, surface effects become more significant, influencing the overall behavior of the material. Consequently, the properties of composite materials can be modified or enhanced. For instance, metallic nanoparticles often serve as highly effective catalysts. In palladium nanoparticles, quantum effects are strongly influenced by the spatial confinement arising from their nanoscale dimensions [31, 32].

The Coulombic interactions and electronic band structure of palladium nanomaterials can vary considerably from those of their bulk counterparts. Such variations alter their electrical and optical properties [33, 34]. For example, optoelectronic technologies are expected to benefit greatly from luminescent devices and light sources based on quantum wires and quantum dots. The reduction of structural defects also plays a critical role in determining the behavior of palladium nanoparticles. During thermal annealing, impurities and intrinsic defects tend to migrate to the surface, enabling a self-purification process in palladium nanoparticles [35]. This improvement in structural integrity significantly influences their overall properties [36].

Optical Properties of Palladium Nanoparticles

The optical properties of palladium nanoparticles are among their most fascinating and valuable features. Several factors influence the optical behavior of nanomaterials, including size, shape, surface texture, doping, and interactions with other materials or nanostructures [37]. Notably, the shape of metal nanostructures significantly affects their optical characteristics. Introducing asymmetry to a nanoparticle can lead to substantial changes in its optical behavior [38].

When materials are reduced to the nanoscale, their optical properties undergo transformation in two primary ways: through quantum confinement and surface plasmon resonance. At these scales, electronic charges become quantum-confined, leading to variations in energy levels. These changes become progressively more distinct as the material transitions from bulk to lower dimensions—two-dimensional, one-dimensional, and ultimately zero-dimensional structures [39].

Metallic nanoparticles exhibiting diverse optical behaviors have been applied in areas such as chemo-optics and bio-nano-photonics. Palladium nanoparticles, in particular, can undergo reversible phase transitions between the solid solution phase and a hybrid phase upon exposure to hydrogen. This phase change results in a structural alteration of the nanoparticles. The localized surface plasmon resonance (LSPR) properties of palladium nanostructures provide a valuable means to investigate metal-hybrid formation during hydrogen absorption and storage processes [40].

Optical measurement

Absorbance

This optical absorption spectrum of palladium nanoparticles was recorded using a UV-visible spectrum. As concentration increases, the absorption rate also increases as more atoms participate in the absorption process.

Optical band gap and absorption coefficient

Optical characteristics, including the optical energy gap, reflective index, and absorption coefficient, describe and categorize materials. Transmittance and absorbance are two metrics that may be used to analyze these properties: the relationship yields and the absorption coefficient [41].

Theories of Optical Properties

Mie theory

Here, the Mie theory is used to compute the optical characteristics of palladium nanoparticles. This theory consists only of periodic presentations of magnetic waves inside a round coordinate by applying spherical harmonics. Both the Mie theory and electromagnetic simulation take size effects and contributions from higher-order modes into account. However, the dipole approximation approach takes such effects into account. The dipole approximation approach, however, may be employed and even changed for simplicity’s sake to corroborate the findings of observations and electrodynamics calculations [42]. This leads to unique optical features, such as distinct absorption bands, which depend on the size and form of the particles, their proximity to one another, the surrounding medium’s dielectric properties, and the metal’s kind and crystal lattice. Few studies have been done on the optical characteristics of palladium nanoparticles, particularly when they come into contact with hydrogen. However, these characteristics are crucial for the creation of photoelectric sensors based on palladium nanoparticles. Recently, an effort to achieve palladium discs with dimensions of a few hundred nm has taken center stage. [43].

Quasistatic theory

The quasistatic approximation requirement for low and slowly varying electrons far from the interband absorption region establishes the LSPR. The logic is invalid for palladium metals when an electron is large enough. Thus, it must be taken into account while performing computations. Additionally, by integrating size adjustment into the theory, also known as the modified long wavelength approximation [44],. The optical responses of big nanoparticles that were produced using the dipole theory may be altered. As a result, the modified polarized.

Catalytic Properties of Palladium Nanoparticles

The current work examines the effects of silica encapsulation on palladium nanoparticles to preserve the strength of the nanoparticles. It also discusses the catalytic characteristics of palladium nanoparticles under hydrogenation conditions. Solutions of palladium nitrate in methyl alcohol were used to produce the nanoparticles, and different reaction conditions were tested to see how efficient the hydrogenation reaction was. In hydrogenation conditions, reaction pressure had an impact on the nanoparticle turnover number, and at high reaction pressure, we looked at the effect of the silica coating on the palladium nanoparticles in order to prevent them from dissolving [45].

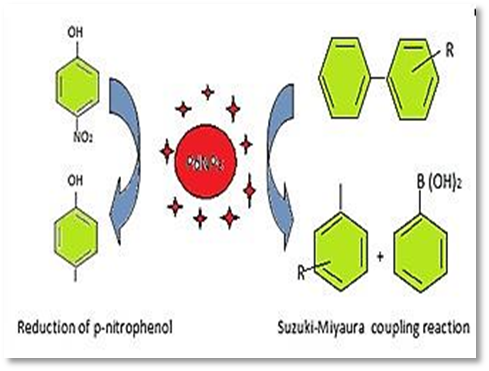

The process of catalysis involves employing a spatial substance called a catalyst to speed up the reaction. For catalysis to occur, the chemical compound must be absorbed on the surface of the material extremely quickly and desorb slowly [47]. Nanoscale materials have higher catalytic activity. As the size of the nanoparticles decreases, the catalytic activity rises. At their bulk scale, noble metals are inert and regarded as subpar catalysts. However, noble metals at the nanoscale are very effective catalysts [48]. For example, the developed palladium nanoparticles from fenugreek tea were tested as a hydrogenation catalyst for 4-nitrophenol, which demonstrated strong catalyst activity, as an illustration of the functional features. Additionally, palladium nanoparticles from fenugreek tea are employed as catalysts in the Suzuki-Miyaura coupling process in place of the conventional palladium complexes to produce biphenyl with outstanding yields [49, 50].

Plasmon Properties of Palladium Nanoparticles

Metal nanostructures have essential characteristics called plasmon resonance. Metal nanoparticle SPR characteristics are very sensitive to composition, size, and shape. Palladium nanostructures with well-defined SPR absorption characteristics that can be systematically modified from the shown to the near-IR spectra scale have been created by the synthesis of nanostructures with regulated size and shape. Only the ultraviolet and visible parts of the spectrum, where palladium nanostructures exhibit wide SPR peaks, are shown by the palladium nanoparticles chemically produced up to this point. Unfortunately, palladium nanoparticles cannot be used in photothermal treatment using NIR lasers because they lack high NIR SPR absorption [51]. Nanoparticles support optical modes called localized surface plasmon resonance, which emit light at the nanoscale. The shape and size of the nanoparticles, as well as the relationship between the optical characteristics of the metal and the surrounding dielectric medium, determined their resonance conditions and mode quality factors as optical modes. As a result, to find the optimal plasmonic nanoparticles for certain applications, it is necessary to investigate the permittivity of the metals for a given nanoparticle shape in a dielectric environment [52].Here, we examine the intercalation process driven by in situ plasmons that are spatially resolved to less than 2 nm. Investigate the photo-reactivity of nanoparticles and establish a link between chemical activity and nanoparticle structure by combining aberration-corrected imaging, diffraction, and atomic power loss spectroscopy. The study has reported the dehydrogenation of certain palladium nanoparticles near gold nanodiscs in an antenna-reactor system. According to recent research, this structure has been effectively employed to generate plasmon areas in reactive but non-plasmon metals [53].

Magnetic Properties of Palladium Nanoparticles

In addition to being distinct from bulk atoms, surface atoms can be modified by connecting with other substances or by capping the nanoparticles. This method offers the option to change the nanoparticles’ physical characteristics by coating them with suitable materials [54]. In reality, it is reasonable to anticipate the activity of non-ferromagnetic core materials created at the nanoscale. Non-magnetic bulk materials can be converted into diamagnetic magnetic palladium ferromagnetism. The behavior is similar to ferromagnetic behavior because of the confined charge at the nanoparticle’s surface. Nanoparticles with a diameter of 2 nm have ordering temperatures due to the significance of spin-orbit interaction, which might result in considerable anisotropy. The 5D band contains localized carriers for nanoparticles smaller than 2 nm. As with nanoparticles, it has a low density of states and becomes diamagnetic. This finding revealed that metallic clusters can acquire ferromagnetic properties by chemically altering the D-band structure [55].

Application of Palladium Nanoparticles

There are different applications of palladium nanoparticles, as shown below.

Sensor

Hydrogen Sensor

The gas sensing ability of the palladium nanoparticles was investigated by monitoring the change in film resistance upon switching the cyclical atmospheric gases from nitrogen to hydrogen. On hydrogen, every film showed an increase in resistance. Palladium nanoparticles can be found in the film region. The hydrogen sensor reaction time has been established. Atoms of hydrogen disperse into the palladium hybrid that is created using a palladium lattice [56]. At ambient temperature, hydrogen may be detected using palladium nanoparticles that have been electrochemically produced and a palladium thin film that has been sputtered. Compared to sputtered palladium thin films, electrochemically produced palladium nanoparticles have superior hydrogen sensing properties, according to the study. In both types of devices, it has been found that the gas-sensing response improves with decreasing grain size. The enhanced gas sensing performance with smaller particle sizes was shown to be caused by chemical and electrical sensitization processes. The palladium-based conductivity sensors were found to be extremely robust and repeatable when tested for various concentrations of hydrogen [57]. Recently, metal oxide has been challenged by palladium or its alloy, which exhibits both of these properties. Hydrogen detection at room temperature has a strong response and selectivity [58]. Palladium hydride is created as a result of the hydrogen atoms being absorbed, which modifies the way that physical energy is expressed. Due to its improved gas responsiveness, actual sensing, and power efficiency, improved electrochemical methods that use the change in palladium even after exposure to hydrogen have been widely studied. The efficacy of the sensing depends heavily on the mass of palladium nanoparticles, which may be modified through the palladium deposit layer [59].

Glucose Sensor

The prospect of good assistance for immobilizing enzymes is provided by nanotechnology. Nanomaterials were used to enhance the stability and catalytic activity of enzymes because they have an advanced, exact surface area for covering a greater number of catalysts, a low concentration transfer resistance, and less fouling. Additionally, the orientation of the enzyme molecules could be selectively changed to enable direct charge transfer between glucose oxidase and the electrode. On a glassy carbon electrode, palladium nanoparticles were electrodeposited, and this catalyst effectively oxidized a solution of glucose and H2O2. .Numerous enzyme-free biosensors for glucose based on palladium nanoparticles have also been developed; these devices showed much increased precision in the conversion of glucose. Palladium nanoparticles may be created in situ within a nafion graphene film that is constructed on a GC electrode. Create a non-enzymatic glucose sensor made of a monolayer and a thin sheet of carbon atoms. The polymeric film confines the palladium nanoparticles. Because of its high electro-catalytic capacity for glucose oxidized in an alkaline medium, as well as its good linear dependency and specificity to glucose concentration change, the nafion graphene palladium glucose sensor is more useful for real-time glucose detection [60].

Hydrogen Storage

At ambient temperatures and pressures, palladium has a well-known capacity to absorb significant volumes of hydrogen. Palladium reacts with hydrogen to generate palladium-hydrogen, which fills the interstitial octahedral spaces of the face-centered cubic crystal. Many studies have looked at the storage capacity of H2 gas in palladium nanowires because of their propensity to hold a huge amount of hydrogen and their enormous interfacial ratio. Using bridge and dehydration, the study has reported on the production of palladium-based nanowire foams and investigated their hydrogen gas storage capacity [61]. After being created by electro-deposition onto porous templates, palladium nanoparticles were sonicated to develop a homogeneous dispersion before being dissolved in water.

Recently, a lot of research has been done on hydrogen storage using palladium and palladium-based nanoparticles. Palladium nanoparticles, in particular, have been investigated as an example framework for the clarification of metal nanomaterial hydrogen storage characteristics. Palladium and hydrogen intake result in the formation of various stages [64]. The alpha state first arises in a solid solution with low hydrogen levels, although the beta state first forms in a metal hydride with high hydrogen levels. The generation of palladium hydride was found to require lower equilibrium forces and hydrogen levels at smaller nanoparticle sizes. Due to the close correlation between their intrinsic characteristics and their shapes, nanoparticle sizes and surface morphology have been important factors in material science. Their geometries and inherent characteristics exhibit a significant correlation [65]. New studies reported that temperature is crucial for hydrogen uptake, absorption, and diffusion and that the shape of palladium may have a significant impact on how much hydrogen can be stored. The phase changes of individual palladium nanomaterials during hydrogen cooling were studied using in situ electron energy loss spectroscopy and an ambient transmission electron microscope. Strong changes between the phases occur in palladium nanocrystals, and surface effects control how the hydrogen absorption pressures depend on diameter. Palladium is alloyed to decrease hydrogen oxidation. Palladium is found in combination with other metals to minimize hydrogen internal stress, which expands the palladium crystal and makes it less susceptible to hydrogen effects. Palladium-based metals have been used in many experiments to limit hydrogen’s internal stress [66].

Catalyst

Palladium nanoparticle synthesis from Artemisia annua was used as a catalyst in the synthesis of several di-indolyl-indolin-2-ones in media, using a noticeable amount. The palladium nanoparticles produced by the biological method have been generated in five cycles without losing any of their catalytic effectiveness. The innovative g-Al₂O₃-based nanocatalysts were used to hydrogenate olefins. They could be recycled five times, and they were immobilized on bayberry tannin-stabilized palladium nanoparticles [67]. By observing the reduction of synthetic dyes, including Coomassie brilliant blue, rhodamine B, methylene blue, and 4-nitrophenol with sodium borohydride, researchers were able to determine the homogeneous catalytic activity of palladium nanoparticles. The results show the potential use of biogenic palladium nanoparticles as nanocatalysts in environmentally friendly remediation of wastewater contamination [68]. Delonix regia leaf extract was used in the synthesis of palladium nanoparticles, which were used as catalysts in the nitro-aromatic hydrogenation process [69]. The Suzuki-Heck coupling reaction was successfully catalyzed in excellent yields and phosphine-free conditions by the comparatively tiny saturated solution of palladium nanoparticles produced by Termenelia arjuna, shown in Fig. 1. This work has applications in synthetic organic chemistry. The elimination of harmful toxic compounds can benefit from the excellent catalytic activity of palladium nanoparticles towards the reduction of dyes like methylene blue and rhodamine-B in the presence of sodium borohydride [70]. The electron relay effect linked to palladium nanoparticles has been responsible for driving the hydrogenation process. Additionally, it has been found that lowering the overall reactivity and raising the nanoparticle level both speed up reactions. A quick and effective method for creating N-alkyl amines has been developed that uses a reducing active catalyst with a heterogeneous catalyst made of palladium nanoparticles stabilized by Acacia gum and sustained by metal oxides and carbon at room temperature and hydrogen stress [71]. Palladium nanoparticles were used in many investigations as Suzuki-Miyaura coupling reaction catalysts to create pharmacological intermediates and other essential compounds. A significant quantity of aryl iodide and aromatic ring bromides that were stronger than the palladium nanoparticles used in the associated procedures were produced. One of the most efficient hydro-de-chlorination catalysts in the ambient environment was found to be palladium. The use of bimetal palladium-iron thin film for chlorination reduction was investigated. Palladium and iron working together resulted in increased sensitivity in the electro-oxidation of contaminated biomolecules [72] and [73].

Fig.1. Suzuki-Miyaura coupling reaction

Antioxidant

Antioxidant properties are indeed present in nanomaterials. Enzymatic and non-enzymatic chemicals that can control the generation of free radicals are the major compounds of antioxidant agents. It has been discovered that such free radicals are exactly what cause cell injury, such as atherosclerosis, cancer, and brain damage [74].Reactive oxygen species, including hydrogen peroxide, peroxides, and hydrogen ions, produce free radicals. Biomolecules are said to tightly regulate the development of free radicals.1,1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) was assessed in human T lymphoblasts to evaluate the antioxidant potential of white tea extract-mediated palladium nanoparticles. White tea extract has significant levels of radical scavenging activity for DPPH at low doses, and the amount of the drug was not an issue. In contrast, the DPPH scavenging capacity of palladium nanoparticles was weak at low concentrations and did not match the anti-oxidation potency of white tea extract until dosages were increased. By measuring the DPPH free radical scavenging activity, the whole antioxidant activity of the greenly produced palladium nanoparticles was determined. The shade of the DPPH solution progressively turned from purple to light yellow throughout the addition of nanoparticles. For example, the antioxidant activity of Lantinan-mediated palladium 150 nanoparticles and palladium 250 nanoparticles was evaluated in addition to the catalytic activity of these nanoparticles. Stabilized free radical molecules were used to assess the antioxidant activity of DPPH. Antioxidant activity is crucial for protecting healthy bodies from the injury that free radicals may cause. The antioxidant activity grew from 20% to 60% when the quantity of palladium 150 nanoparticles was raised from 0.27 to 1.33 milligrams/mL, demonstrating efficient free radical control by palladium 150 nanoparticles [75].

Antimicrobial

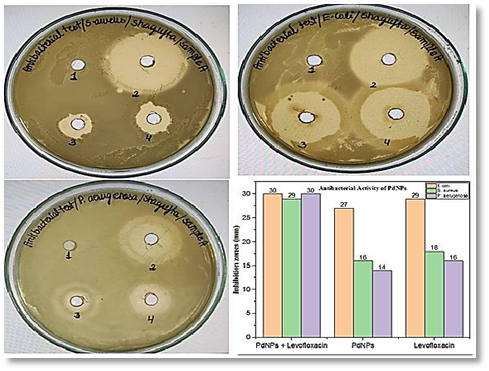

Significant action against antifungal and antibacterial organisms was shown by these greenly produced palladium nanoparticles from Rosa damascena leaf extract. Examine the toxic activity of palladium nanoparticles on E. coli (gram-negative) and Staphylococcus aureus during the 24-hour test period. Candida albicans, Aspergillus niger, and Aspergillus flavus were all successfully eradicated by the palladium nanoparticles, showing remarkable antifungal activity, as shown in Fig. 2 [76] [77]. It has been demonstrated that the antibacterial effects of palladium nanoparticles reflect their dimension. It was discovered that palladium nanoparticles are still more harmful to gram-positive Staphylococcus aureus bacteria than palladium ions. Palladium nanoparticles with a diameter of 2 nm or less were more hazardous than those with a diameter of 2.5 or 3.1 nm. The highest antifungal activity, even against fungi, was seen for the diameters of 200, 220, and 250 nm in the green production and characterization of palladium nanoparticles using flavonoids derived from quercetin. Palladium nanoparticles created from the fruit extract of Couroupita guianensis were tested at a dose of 25 mg/ml, and they demonstrated remarkable antimicrobial application even against gram-positive and gram-negative microorganisms [78]. Additionally, the substance successfully combated a brand new drug-resistance diagnostics microbial culture of Cronobacter sakazakii variety AMD04 while exhibiting outstanding antibacterial and anti-biofilm applications. Palladium nanoparticles were shown to have minimal bactericidal and prohibitive concentration MIC and MBC of 0.06 and 0.12 mm, respectively [79]. The antibacterial and antifungal application of the phyto-synthesized palladium nanoparticles against Candida albicans and Bacillus subtilis has been shown. Palladium ions were mixed with leaf extract of Santalum album in a 9:1 ratio and left to set at ambient temperature for four days to produce the palladium nanoparticles. The generated round-shaped palladium nanoparticles ranged in size from 10 to 40 nm on average. In comparison to gram-positive bacteria, nanoparticles demonstrated more powerful antibacterial action against gram-negative bacteria [80].

Fig.2. Anti-bacterial activity

Conclusion

This paper concludes that palladium nanoparticles possess outstanding properties and offer versatile applications across various fields. The incorporation of bimetallic and metal oxide-supported structures enhances the characteristics and performance of palladium nanoparticles. These nanoparticles exhibit a range of valuable properties, including optical, plasmonic, catalytic, and magnetic behavior.

Due to these desirable features, palladium nanoparticles are widely utilized in high-performance catalysts and sensor technologies. Their synthesis has been explored through numerous biological reduction methods, with plant extracts playing a key role in eco-friendly production. These biologically synthesized palladium nanoparticles have demonstrated catalytic efficiency in important reactions such as the Suzuki–Miyaura coupling, Heck reaction, and dye degradation.

Moreover, palladium and palladium-based nanostructures have shown promising applications in diverse areas, including hydrogen and glucose sensors, as well as in antioxidant and antimicrobial activities.

Conflict of interest: Authors declare that no any conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

1. Jadoun, S.; Arif , R.;Jangid, NK.; Meena, RK. Green synthesis of nanoparticles using plant extracts: A review. Environmental Chemistry Letters. 2021, 19(1), 355-74.

2. Kanchi, S.; Ahmed, S. eds.; Green metal nanoparticles: synthesis, characterization and their applications. John Wiley & Sons. 2018.

3. Mousavi, S.M.; Hashemi, S.A.; Ghasemi, Y.; Atapour, A.; Amani, A.M.; Savar Dashtaki, A.; Babapoor, A. ; Arjmand, O. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles toward bio and medical applications: review study. Artificial cells, nanomedicine, and biotechnology. 2018,46(sup3), 855-872.

4. Vajtai, R. Science and engineering of nanomaterials. Springer Handbook of Nanomaterials. 2013,1-36.

5. Dizaj, S.M.; Lotfipour, F.; Barzegar-Jalali, M.; Zarrintan, M.H.; Adibkia, K. Antimicrobial activity of the metals and metal oxide nanoparticles. Materials Science and Engineering: C. 2014,44, 278-284.

6. Mittal, J.; Batra, A.; Singh, A.; Sharma, M.M. Phytofabrication of nanoparticles through plant as nanofactories. Advances in Natural Sciences: Nanoscience and Nanotechnology. 2014, 5(4),043002.

7. Siddiqi, K.S.; Husen, A. Green synthesis, characterization and uses of palladium/platinum nanoparticles. Nanoscale research letters. 2016, 11,1-13.

8. Agostini, G.; Piovano, A.; Bertinetti, L.; Pellegrini, R.; Leofanti, G.; Groppo, E.; Lamberti, C. Effect of different face centered cubic nanoparticle distributions on particle size and surface area determination: a theoretical study. The Journal of Physical Chemistry C. 2014, 118(8), 4085-4094.

9. Wang, Y.; Xie, S.; Liu, J.; Park, J.;Huang, C.Z.; Xia, Y. Shape-controlled synthesis of palladium nanocrystals: a mechanistic understanding of the evolution from octahedrons to tetrahedrons. Nano letters. 2013, 13(5), 2276-2281.

10. Long, N.V.; Hayakawa, T.; Matsubara, T.; Chien, N.D.; Ohtaki, M.; Nogami, M. Controlled synthesis and properties of pallad;um nanoparticles. Journal of Experimental Nanoscience. 2012, 7(4),426-439.

11. Joudeh, N.; Saragliadis, A.; Koster, G.; Mikheenko, P.; Linke, D. Synthesis methods and applications of palladium nanoparticles: A review. Frontiers in Nanotechnology. 2022, 4,106-608.

12. Michałek, T.; Hessel, V.; Wojnicki, M. Production, recycling and economy of palladium: A critical review. Materials. 2023, 17(1), 45.

13. Bi, S.; Srivastava,R. A Review on Green Synthesis of Palladium Nanoparticles and their Applications. International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research. 2022, 13, (08), 1015–30.

14. Vinodhini, S.; Vithiya, B.S.M.;Prasad, T.A.A. Green synthesis of palladium nanoparticles using aqueous plant extracts and its biomedical applications. Journal of King Saud University-Science. 2022, 34(4), 102-017.

15. Lengke, M.F.; Fleet, M.E.; Southam, G. Synthesis of palladium nanoparticles by reaction of filamentous cyanobacterial biomass with a palladium (II) chloride complex. Langmuir. 2007, 23(17), 8982-8987.

16. Bi, S.; Srivastava, R. Rosa damascena leaf extract mediated palladium nanoparticles and their anti-inflammatory and analgesic applications. Inorganic Chemistry Communications. 2024,162,112-122.

17. Phan, T.T.V.; Huynh, T.C.; Manivasagan, P.; Mondal, S.; Oh, J. An up-to-date review on biomedical applications of palladium nanoparticles. Nanomaterials. 2019,10(1), 66.

18. Hussain, I.;Singh, N.B.; Singh, A.; Singh, H. ; Singh, S.C. Green synthesis of nanoparticles and its potential application. Biotechnology letters. 2016, 38, 545-560.

19. Haleemkhan, A.A.; Naseem, B.;Vardhini, B.V. Synthesis of nanoparticles from plant extracts. Int J Mod Chem Appl Sci. 2015, 2(3),195-203.

20. Makarov, V.V.; Love, A.J.; Sinitsyna, O.V.; Makarova, S.S.; Yaminsky, I.V.; Taliansky, M.E.; Kalinina, N.O. “Green” nanotechnologies: synthesis of metal nanoparticles using plants. Acta Naturae (англоязычная версия). 2014, 6(1 (20)), 35-44.

21. Kumar, A.; Mohammadi, M.M.;Swihart, M.T. Synthesis, growth mechanisms, and applications of palladium-based nanowires and other one-dimensional nanostructures. Nanoscale. 2019, 11(41),19058-19085.

22. Sonbol, H.; Ameen, F.; AlYahya, S.; Almansob, A.; Alwakeel, S. Padina boryana mediated green synthesis of crystalline palladium nanoparticles as potential nanodrug against multidrug resistant bacteria and cancer cells. Scientific reports. 2021,11(1), 54-44.

23. Kalaiselvi, A.; Roopan, S.M.; Madhumitha, G.; Ramalingam, C. ; Elango, G. Synthesis and characterization of palladium nanoparticles using Catharanthus roseus leaf extract and its application in the photo-catalytic degradation. Spectrochimica Acta Part A: Molecular and Biomolecular Spectroscopy. 2015,135,116-119.

24. Bi, S.; Srivastava, R. Rosa damascena flower mediated phytofabrication of palladium nanoparticles, in-vitro and in-vivo applications. Materials Today: Proceedings. 2023.

25. Azizi, S.; Shahri, M.M.; Rahman, H.S.; Rahim, R.A.; Rasedee, A. ; Mohamad, R. Green Synthesis Palladium Nanoparticles Mediated by White Tea (Camellia sinensis) Extract with Antioxidant, Antibacterial, and Antiproliferative Activities Toward the Human Leukemia (MOLT-4) Cell Line. International Journal of Nanomedicine. 2022,17,1227-1228.

26. Can, M. Green gold nanoparticles from plant-derived materials: An overview of the reaction synthesis types, conditions, and applications. Reviews in Chemical Engineering, 2020. 36(7), 859-877.

27. Al-Fakeh, M.S.; Osman, S.O.M.; Gassoumi, M.; Rabhi, M.; Omer, M. Characterization, antimicrobial and anticancer properties of palladium nanoparticles biosynthesized optimally using Saudi propolis. Nanomaterials. 2021,11(10), p.2666.

28. Khan, I.; Saeed, K. ; Khan, I. Nanoparticles: Properties, applications and toxicities. Arabian journal of chemistry. 2019,12(7), pp.908-931.

29. Arsiya, F.;Sayadi, M.H. ;Sobhani, S. Green synthesis of palladium nanoparticles using Chlorella vulgaris. Materials Letters. 2017,186, 113-115.

30. Hussain, I.; Singh, N.B.; Singh, A.; Singh, H. ;Singh, S.C. Green synthesis of nanoparticles and its potential application. Biotechnology letters. 2016, 38, 545-560.

31. Mittal, A.K.; Chisti, Y.; Banerjee, U.C. Synthesis of metallic nanoparticles using plant extracts. Biotechnology advances. 2013, 31(2), 346-356.

32. Fahmy, S.A.; Preis, E.; Bakowsky, U.; Azzazy, H.M.E.S. Palladium nanoparticles fabricated by green chemistry: Promising chemotherapeutic, antioxidant and antimicrobial agents. Materials. 2020, 13(17), 3661.

33. Shah, M.; Fawcett, D.;Sharma, S.; Tripathy, S.K. ;Poinern, G.E.J. Green synthesis of metallic nanoparticles via biological entities. Materials.2015,8(11), 7278-7308.

34. Bi, S.; Srivastava, R.; Ahmad, T. The Potential Antifungal Activity of the Developed Palladium Nanoparticles. Biomedical and Pharmacology Journal. 2024,17(4).

35. Kuppusamy, P.;Yusoff, M.M.; Maniam, G.P. ; Govindan, N. Biosynthesis of metallic nanoparticles using plant derivatives and their new avenues in pharmacological applications–An updated report. Saudi Pharmaceutical Journal. 2016, 24(4), 473-484.

36. Mie, R.; Samsudin, M.W.; Din, L.B.; Ahmad, A.; Ibrahim, N. ; Adnan, S.N.A. Synthesis of silver nanoparticles with antibacterial activity using the lichen Parmotrema praesorediosum. International journal of nanomedicine, 2014,121-127.

37. Patil, S.P.; Burungale, V.V. Physical and chemical properties of nanomaterials. Nanomedicines for breast cancer theranostics.2020, 17-31.

38. Feng, E.Y.;Zelaya, R.; Holm, A.;Yang, A.C. ; Cargnello, M. Investigation of the optical properties of uniform platinum, palladium, and nickel nanocrystals enables direct measurements of their concentrations in solution. Colloids and Surfaces A: Physicochemical and Engineering Aspects. 2020, 601,125-007.

39. Majeed, M.S.; Dhahir, M.K. ; Mahdy, Z.F. Studying the Structure and the Optical Properties of Pd Nanoparticles Affected by Precursor Concentration. Int. Journal of Engineering Research and Applications. 2015, 6(1),12-17.

40. Valizade-Shahmirzadi, N.; Pakizeh, T. Optical characterization of broad plasmon resonances of Pd/Pt nanoparticles. Materials Research Express. 2018, 5(4), 045-038.

41. Kracker, M.; Worsch, C.; Rüssel, C. Optical properties of palladium nanoparticles under exposure of hydrogen and inert gas prepared by dewetting synthesis of thin-sputtered layers. Journal of nanoparticle research.2013, 15, 1-10.

42. Ismail, E.; Khenfouch, M.; Dhlamini, M.; Dube, S.; Maaza, M. Green palladium and palladium oxide nanoparticles synthesized via Aspalathus linearis natural extract. Journal of Alloys and Compounds. 2017,695, 3632-3638.

43. Kulikova, D.P.; Dobronosova, A.A.; Kornienko, V.V.; Nechepurenko, I.A.; Baburin, A.S.; Sergeev, E.V.; Lotkov, E.S.; Rodionov, I.A.; Baryshev, A.V. ; Dorofeenko, A.V. Optical properties of tungsten trioxide, palladium, and platinum thin films for functional nanostructures engineering. Optics express. 2020, 28(21), 32049-32060.

44. Al Ahsan, M.; Hosur, M.; Tareq, S.H.; Hasan, S.K. Quasi-static compression characterization of binary nanoclay/graphene reinforced carbon/epoxy composites subjected to seawater conditioning. Materials Research Express. 2020, 7(1), 015033.

45. Umegaki, T.; Satomi, Y. ; Kojima, Y. Catalytic properties of palladium nanoparticles for hydrogenation of carbon dioxide into formic acid. Journal of the Japan Institute of Energy. 2017, 96(11), 487-492.

46. Ament, K.; Wagner, D.R.; Götsch, T.; Kikuchi, T.; Kröhnert, J.; Trunschke, A.; Lunkenbein, T.; Sasaki, T.; Breu, J. Enhancing the catalytic activity of palladium nanoparticles via sandwich-like confinement by thin titanate nanosheets. ACS catalysis. 2021,11(5),2754-2762.

47. Mallikarjuna, K.; Bathula, C.; Buruga, K.; Shrestha, N.K.; Noh, Y.Y. ; Kim, H.,. Green synthesis of palladium nanoparticles using fenugreek tea and their catalytic applications in organic reactions. Materials Letters. 2017, 205, 138-141.

48. Gavia, D.J.; Young, S.S. Catalytic properties of unsupported palladium nanoparticle surfaces capped with small organic ligands. ChemCatChem. 2015, 7(6), 892-900.

49. Nasrollahzadeh, M. Green synthesis and catalytic properties of palladium nanoparticles for the direct reductive amination of aldehydes and hydrogenation of unsaturated ketones. New Journal of Chemistry. 2014, 38(11), 5544-5550.

50. Santoshi, K.A.; Venkatesham, M.; Ayodhya, D.; Veerabhadram, G.; Green synthesis, characterization and catalytic activity of palladium nanoparticles by xanthan gum. Applied Nanoscience. 2015, 5, 315-320.

51. De Marchi, S.; Núñez-Sánchez, S.; Bodelón, G.; Pérez-Juste, J. ; Pastoriza-Santos, I. Pd nanoparticles as a plasmonic material: synthesis, optical properties and applications. Nanoscale. 2020, 12(46), 23424-23443.

52. Huang, X.; Tang, S.; Mu, X., Dai, Y.; Chen, G.; Zhou, Z.; Ruan, F.; Yang, Z. ; Zheng, N. Freestanding palladium nanosheets with plasmonic and catalytic properties. Nature nanotechnology. 2011, 6(1), 28-32.

53. Vadai, M.; Angell, D.K.; Hayee, F.; Sytwu, K.; Dionne, J.A. In-situ observation of plasmon-controlled photocatalytic dehydrogenation of individual palladium nanoparticles. Nature Communications. 2018, 9(1), 46-58.

54. Baran, T.; Nasrollahzadeh, M. Facile synthesis of palladium nanoparticles immobilized on magnetic biodegradable microcapsules used as effective and recyclable catalyst in Suzuki-Miyaura reaction and p-nitrophenol reduction. Carbohydrate polymers. 2019, 222,115-029.

55. Baghayeri, M.; Alinezhad, H.; Tarahomi, M.; Fayazi, M.; Ghanei-Motlagh, M.; Maleki, B. A non-enzymatic hydrogen peroxide sensor based on dendrimer functionalized magnetic graphene oxide decorated with palladium nanoparticles. Applied Surface Science. 2019, 478, pp.87-93.

56. Darmadi, I.; Nugroho, F.A.A.; Langhammer, C. High-performance nanostructured palladium-based hydrogen sensors—current limitations and strategies for their mitigation. ACS sensors. 2020, 5(11), 3306-3327.

57. Wang, B.; Sun, L.; Schneider-Ramelow, M.; Lang, K.D.; Ngo, H.D. Recent advances and challenges of nanomaterials-based hydrogen sensors. Micromachines. 2021,12(11),14-29.

58. Ndaya, C.C.; Javahiraly, N.; Brioude, A. Recent advances in palladium nanoparticles-based hydrogen sensors for leak detection. Sensors. 2019, 19(20), 44-78.

59. Lerch, S.; Reinhard, B.M. Effect of interstitial palladium on plasmon-driven charge transfer in nanoparticle dimers. Nature Communications. 2018, 9(1),1608.

60. Singh, B.;Bhardwaj, N.; Jain, V.K. ; Bhatia, V. Palladium nanoparticles decorated electrostatically functionalized MWCNTs as a non enzymatic glucose sensor. Sensors and Actuators A: Physical, 2014, 220, 126-133.

61. Konda, S. K.; Aicheng Chen. Palladium based nanomaterials for enhanced hydrogen spillover and storage. Materials Today. 2016, 19(2), 100-108.

62. Nair, A.AS; Ramaprabhu, S.; N. A. Hydrogen storage performance of palladium nanoparticles decorated graphitic carbon nitride. International journal of hydrogen energy. 2015, 40.8, 3259-3267.

63. Ament, K.; Kobayashi, H.; Kusada, K.; Breu, J. ; Kitagawa, H. Enhancing Hydrogen Storage Capacity of Pd Nanoparticles by Sandwiching between Inorganic Nanosheets. Zeitschrift für anorganische und allgemeine Chemie. 2022, 648(10), 00370.

64. Felipe J.V.; Rafael I G.; Diego T.; José R.; Juan A. V.; Miguel K.; Eduardo M.B. Hydrogen storage in palladium hollow nanoparticles. The Journal of Physical Chemistry C. 2016, 120(41), 23836-23841.

65. Zalineeva, A.; Baranton, S.; Coutanceau, C. ; Jerkiewicz, G. Octahedral palladium nanoparticles as excellent hosts for electrochemically adsorbed and absorbed hydrogen. Science Advances.2017, 3(2),1600-542.

66. Zhang, J.H.; Wei, M.J.; Lu, Y.L.; Wei, Z.W.; Wang, H.P.;Pan, M. Ultrafine palladium nanoparticles stabilized in the porous liquid of covalent organic cages for photocatalytic hydrogen evolution. ACS Applied Energy Materials. 2020, 3(12), 12108-12114.

67. Edayadulla, N.; Nagaraj B.; Yong R.L. Green synthesis and characterization of palladium nanoparticles and their catalytic performance for the efficient synthesis of biologically interesting di (indolyl) indolin-2-ones. Journal of Industrial and Engineering Chemistry. 2015, 21,1365-1372.

68. Şahin Ü, Ş.; Ünlü, A.; Ün, İ.; Ok, S. Green synthesis, characterization and catalytic activity evaluation of palladium nanoparticles facilitated by Punica granatum peel extract. Inorganic and Nano-Metal Chemistry. 2021, 51(9), pp.1232-1240.

69. Garai, C.; Hasan, S.N.; Barai, A.C.; Ghorai, S.; Panja, S.K.; Bag, B.G. Green synthesis of Terminalia arjuna-conjugated palladium nanoparticles (TA-PdNPs) and its catalytic applications. Journal of Nanostructure in Chemistry. 2018, 8, 465-472.

70. Emam, H.E.; Saad, N.M.; Abdallah, A.E.; Ahmed, H.B. Acacia gum versus pectin in fabrication of catalytically active palladium nanoparticles for dye discoloration. International journal of biological macromolecules, 2020, 156, 829-840.

71.Lakshmipathy, R.; Palakshi, R. B.; Sarada, N.C.; Chidambaram, K. ; Khadeer, P. S.K. Watermelon rind-mediated green synthesis of noble palladium nanoparticles: catalytic application. Applied Nanoscience. 2015, 5, 223-228.

72. Veisi, H.; Faraji, A.R.; Hemmati, S.; Gil, A. Green synthesis of palladium nanoparticles using Pistacia atlantica kurdica gum and their catalytic performance in Mizoroki–Heck and Suzuki–Miyaura coupling reactions in aqueous solutions. Applied Organometallic Chemistry. 2015, 29(8), 517-523.

73. Kora, A.J.; Rastogi, L. Green synthesis of palladium nanoparticles using gum ghatti (Anogeissus latifolia) and its application as an antioxidant and catalyst. Arabian Journal of Chemistry. 2018, 11(7), 1097-1106.

74. Anju, A.R.Y.A.; Gupta, K. ; Chundawat, T.S. In vitro antimicrobial and antioxidant activity of biogenically synthesized palladium and platinum nanoparticles using Botryococcus braunii. Turkish Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences. 2020, 17(3), 299.

75. Han, Z.; Dong, L.; Zhang, J.; Cui, T.;Chen, S.; Ma, G., Guo, X. ; Wang, L.Green synthesis of palladium nanoparticles using lentinan for catalytic activity and biological applications. RSC advances. 2019, 9(65), 38265-38270.

76. Bi, S, and Nabeel A. Green synthesis of palladium nanoparticles and their biomedical applications. Materials Today: Proceedings. 2022, 62, 3172-3177

77. Chlumsky, O.; Purkrtova, S.; Michova, H.; Sykorova, H.; Slepicka, P.; Fajstavr, D.; Ulbrich, P.; Viktorova, J. ; Demnerova, K. Antimicrobial properties of palladium and platinum nanoparticles: A new tool for combating food-borne pathogens. International journal of molecular sciences. 2021, 22(15), 7892.

78. Gnanasekar, S.;Murugaraj, J.; Dhivyabharathi, B.; Krishnamoorthy, V.;Jha, P.K.; Seetharaman, P.; Vilwanathan, R. ; Sivaperumal, S. Antibacterial and cytotoxicity effects of biogenic palladium nanoparticles synthesized using fruit extract of Couroupita guianensis Aubl. Journal of applied biomedicine. 2018, 16(1), 59-65.

79. Chang, Y.; Xing, M.; Hu, X.; Feng, H.; Wang, Y.; Guo, B.; Sun, M.; Ma, L. ;Fei, P. Antibacterial activity of Chrysanthemum buds crude extract against Cronobacter sakazakii and its application as a natural disinfectant. Frontiers in Microbiology. 2021, 11, 632-177.

80. Sharmila, G.; Haries, S.; Fathima, M.F.; Geetha, S.; Kumar, N.M.; Muthukumaran, C. Enhanced catalytic and antibacterial activities of phytosynthesized palladium nanoparticles using Santalum album leaf extract. Powder Technology. 2017, 320, 22-26.