INTRODUCTION

Ensuring sustainable energy supply is vital for global economic growth and the overall well-being of humanity. Currently, over 80% of the world’s energy production relies on carbon-based fossil fuels such as coal, oil, and natural gas [1]. However, most semiconductor photocatalysts possess a wide band gap, typically in the ultraviolet (UV) region—equal to or greater than 3.2 eV—which significantly limits their applicability due to their poor absorption of visible light [2].

Various strategies have been explored to overcome this limitation, including doping with non-metals and co-doping with polymeric materials to reduce the band gap. These approaches have led to the development of novel photocatalysts capable of degrading organic pollutants under visible light irradiation [3]. Titanium dioxide (TiO₂), in particular, is recognized for its unique electronic properties, along with excellent thermal and chemical stability. To further enhance its photocatalytic efficiency, techniques such as metal or non-metal doping [4], and coupling with other semiconductors [5], have been extensively applied. These modifications contribute to increased surface area and reduced particle size, thereby improving the separation of electron-hole (e⁻–h⁺) pairs and overall photocatalytic performance.

In the present study, a green synthesis approach was employed for the first time to prepare a TiO₂ composite using Syzygium cumini leaf extract via the impregnation method. This method aims to enhance visible light absorption by increasing the surface area of the composite. The photocatalytic activity was then evaluated through the degradation of methylene blue (MB) under visible light irradiation.

MATERIALS AND METHOD

2.1 Synthesis of Photocatalysts

2.1.1 Synthesis of Pure TiO₂ Photocatalyst

Pure TiO₂ was synthesized through a thermal treatment method. The TiO₂ precursor was placed in a covered crucible under ambient atmospheric conditions. It was initially dried at 80 °C for 24 hours. Subsequently, the dried precursor was transferred to a muffle furnace and calcined at 550 °C for 3 hours, maintaining a heating rate of 10 °C/min. The resulting yellow product was collected, ground into a fine powder, and stored for further use [6].

2.1.2 Preparation of Syzygium cumini Leaf Extract

Fresh Syzygium cumini leaves were collected from the campus and thoroughly washed with double-distilled water to eliminate surface impurities. The cleaned leaves were dried at 60 °C, then ground into a fine powder. For extract preparation, 20 g of the powdered leaves were mixed with 100 mL of double-distilled water and heated at 80 °C in a water bath for 60 minutes. After heating, the mixture was filtered using Whatman filter paper. The resulting extract was used as a natural capping and stabilizing agent in the synthesis of the TiO₂ composite.

2.1.3 Green Synthesis of TiO₂ Using Syzygium cumini Leaf Extract

The green synthesis of TiO₂ composite photocatalyst was carried out using an impregnation method. In this process, equal proportions (1:1 ratio) of previously prepared TiO₂ powder and Syzygium cumini leaf extract were mixed and dispersed in 1 M HCl solution. The mixture was magnetically stirred for 3 hours to ensure proper interaction. The resulting product was separated via centrifugation and washed sequentially with ethanol and deionized water. The final product was dried at 80 °C for 1 hour in a hot air oven. The resulting TiO₂ composite, modified with Syzygium cumini leaf extract, was obtained as a yellow-colored powder [7].

2.2 Characterization Techniques

The optical properties of the synthesized materials were evaluated using UV-Visible spectroscopy in the 200–800 nm wavelength range with a Shimadzu UV-3101 PC spectrophotometer. FT-IR spectra were recorded in transmittance mode using a SHIMADZU FTIR spectrometer. Samples were prepared as KBr pellets mixed with the photocatalyst powder.

2.3 Evaluation of Photocatalytic Activity

The photocatalytic performance of the synthesized composite was assessed by monitoring the degradation of Rhodamine B (Rh-B) under natural sunlight. A 1×10⁻⁵ M Rh-B dye solution was prepared in deionized water (pH 7.6). For the photocatalytic experiment, 50 mL of this solution was placed in a beaker, and 0.1 g of the photocatalyst (2 g/L) was added. The suspension was stirred in the dark for 30 minutes to establish adsorption-desorption equilibrium between the dye and the catalyst.

Subsequently, the dye suspension was exposed to sunlight in open-air conditions while being agitated at a constant speed of 790 rpm using an electromagnetic stirrer. At regular time intervals, aliquots of the reaction mixture were withdrawn, centrifuged to remove catalyst particles, and filtered through Millipore filter paper. The clear filtrates were analyzed using a UV-Visible spectrophotometer. The maximum absorbance for Rh-B dye was recorded at 553 nm.

The degradation efficiency (%) of the dye was calculated using the following formula: Degradation Efficiency (%)=(C0−CC0)×100\text{Degradation Efficiency (\%)} = \left( \frac{C_0 – C}{C_0} \right) \times 100Degradation Efficiency (%)=(C0C0−C)×100

Where:

- C0C_0C0 = Initial concentration of dye

- CCC = Final concentration after irradiation

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

3.1 Characterization Technique

3 FT-IR Analysis

The molecular geometry, information about its functional groups and inter/intra molecular interactions of the resulting composite photocatalysts are characterized by FT-IR spectroscopy. Fig 3.1 shows the FT-IR spectrum of modified TiO2 sample. The main characteristic peaks of modified sample can be assigned as follows: The main absorption bands at 1435, 1473, 1539 and 1411 cm-1 are allocated to aromatic C-N stretching and the conjugated C=N stretching can be seen at 1593 and 1539 [9]. Moreover, the small bands at 2376 cm-1 can be assigned likely to the stretching vibration modes of NH2 and NH groups, while the bands at 3917-3774 cm-1 corresponds to the absorbed moisture i.e., the presence of water molecule [10].

According to the result, the absorption spectrum revealed the presence of various bio compounds in the leaf sample of Syzygium cumini. Strong- broad and weak-broad bands around 3689.83 cm1 to 3415.93 cm-1 represented –OH group of alcohol. The band between 2922.16 cm-1 and 2854.65 cm-1 represented -CH group of alkanes and the band around 1718.58 cm-1 showed strong C=O stretching of aldehyde. The band around1660-1539 cm-1 revealed that the presence of C=C stretching of conjugated alkenes have medium di substitute (trans) groups in the leaf sample. The spectrum shows an intense band at 520.78 cm-1 corresponding to Ti-O-Ti vibrations, which conform the formation of TiO2 sample as well as the leaf extract sample containing halo compounds with strong stretching of –C-I groups [75]. 1718.58 cm-1 showed strong C=O stretching of aldehyde. The band around 1660-1539 cm-1 revealed that the presence of C=C stretching of conjugated alkenes have medium di substitute (trans) groups in the leaf sample. The spectrum shows an intense band at 520.78 cm-1 corresponding to Ti-O-Ti vibrations, which conform the formation of TiO2 sample as well as the leaf extract sample containing halo compounds with strong stretching of –C- I groups [8].

Fig 3.1 FT-IR spectrum of modified TiO

3.1.1 Photocatalytic Activity Measurements

To Evaluate the photocatalytic activity of prepared sample TiO2 modified by Syzygium cumini leaf extract towards dye degradation. Methylene Blue (MB) was used as the model pollutant for the degradation. The suspensions of the catalyst in dye solution were subjected to sunlight for 180 minutes with continuous stirring. After every 30 minutes, 5 ml aliquots were pipette out and centrifuged. The Photocatalytic degradation of the dye was monitored using UV spectroscopic analysis technique. The absorbance of the clear supernatants was determined at 688.5 nm wavelength against blank solution.

3.2 Degradation of Dye during the Course of Reaction

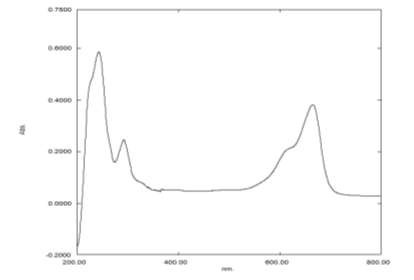

Fig. 3.2, depicts the spectrum of MB dye. Fig. 3.3 depict the degradation spectrU of MB dye using modified TiO2 photocatalyst. From the figure it is explained that as the reaction time increases, the primary absorption peak of MB at 688.5 nm almost disappears at the end of 180 minutes irradiation. It indicates that the main chromophores in the MB dye solution are destroyed using modified TiO2 photocatalyst and proves that 97 % dye is decomposed in the system.

Fig. 3.2 UV Spectrum of Methylene Blue Dye.

Fig. 3.3 Combined Degradation Spectra of Dye during the Course of Reaction.

3.2 Efficiency of Photocatalyst

Efficiency of photocatalytic process of methylene blue dye can be given in the Table-1 and Fig 3.4

Table -1 Degradation Efficiency of Modified TiO2 Photocatalyst.

| Photocatalyst | Efficiency % |

| Without Photocatalyst in the Presence of Sunlight at pH 8.6 | 9 |

| Photocatalyst in the Absence of Sunlight at pH 8.6 | 19 |

| Photocatalyst in the Presence of Sunlight at pH 8.6 | 94 |

Fig 3. Degradation Efficiency of Methylene Blue Dye.

CONCLUSION

This study demonstrated that methylene blue can be effectively photodegraded under sunlight in the presence of the synthesized photocatalyst. The duration of irradiation plays a crucial role in the degradation process. In the conducted experiments, an irradiation period of 180 minutes with 30-minute intervals resulted in approximately 97% degradation of methylene blue using the prepared photocatalyst. Characterization through FTIR spectroscopy confirmed the formation of TiO₂, indicated by a strong absorption band at 520.78 cm⁻¹ corresponding to Ti–O–Ti vibrations. Additionally, the Syzygium cumini leaf extract used in the synthesis was found to contain halo compounds with distinct –C–I group stretching. The use of a natural, renewable, and eco-friendly leaf extract for the green synthesis of modified TiO₂ not only supports sustainable practices but also yields a photocatalyst with excellent activity against dye pollutants. These findings suggest its promising application in water purification and dye effluent treatment systems.

REFERENCES

[1] R. van de Krol, Y.Q. Liang, J. Schoonman, Solar hydrogen production with nanostructured metal oxides, J Mater Chem, 18 (2008) 2311-2320. [2] Observer, Worldwide electricity production from renewable energy sources, in: Observer (Ed.), Paris, 2012.

[3] J.S. Roel Van de Krol, Photo-electrochemical production of hydrogen, in: Sustainable Energy Technologies: Options and Prospects, Springer, 2008, pp. 121-142.

[4] Mathur, N, Bhatnagar, P & Bakre, P 2005, ‘Assessing mutagenicity of textile dyes from Pali (Rajasthan) using ames bioassay’, Applied Ecology and Environmental Research, vol. 4, no. 1, pp. 111-118.

[5] A. Fujishima, X.T. Zhang, D.A. Tryk, TiO2 photocatalysis and related surface phenomena, Surf Sci Rep, 63 (2008) 515-582.

[6] J. Mao, T. Peng, X. Zhang, K. Li, L. Ye & L. Zan 2013, ‘Effects of graphitic carbon nitride microstructures on the activity and selectivity of photocatalytic CO2 reduction under visible light’, Catalysis Science and Technology, vol. 3, pp.1253-1260. \

[7] Q. Xiang, J. `Ye, & M. JaronicL. 2011, ‘Preparation and enhanced visible light photocatalytic H2-production activity of graphene C3N4 composites’, The Journal of Physical Chemistry C, vol. 115, pp. 7355-7368.

[8] Y. Gao, Z. Masuda, T. Peng, Yonezawa and K. Koumoto, Room temperature deposition of a TiO2 thin film from aqueous peroxotitanate solution J. Mater. Chem.13 (2003) 608-610.

[9] K. Gibson, T. Glaser, E. Mike, M. Marzini, S. Tragl, M. Binnewies, H.A. Mayer, & H.J. Meyar. 2008, ‘Preparation of carbon nitride materials by polycondensation of the single source precursor amino dichlorotriazine’, Materials Chemistry and Physics, vol. 112, pp. 52-56.

[10] P.C.V. Regunton, D.E.P. Sumalapao, N.R. Villarante. Biosorption of methylene blue from aqueous solution by coconut (Cocos nucifera) shell- derived activated carbon-chitosan composite. Orient. J. Chem. 2018, 34, 115–124.