Introduction: The primary purpose of biomaterials is to replace damaged or diseased tissues. First-generation biomaterials were designed to be bio-inert, mainly interacting with host tissues to minimize inflammation or wound formation. In 1969, Professor Larry Hench introduced bioactive glasses, which facilitated interfacial bonding with surrounding tissues, marking the development of second-generation biomaterials. Third-generation biomaterials, including bio-glasses capable of gene activation, were employed for tissue restoration and healing [1].

Hench proposed that strong bonding between bone and synthetic materials arises from chemical reactions occurring on the glass surface. These reactions enable bioactive glasses to form strong bonds with bone, effectively replacing damaged tissue. Due to these properties, bio-glass is considered a highly suitable biomaterial for medical applications. Typically, bio-glass comprises silicon, sodium, potassium, magnesium, oxygen, calcium, and phosphorus—elements naturally present in the human body—thus minimizing toxicity. Several studies have shown that during bone formation and bonding, ion concentrations released from bio-glass do not reach levels harmful to surrounding tissues [2].

Commonly studied bioactive glasses include 45S5 (45 SiO₂, 24.5 CaO, 24.5 Na₂O, 6 P₂O₅ wt%) [3] and 1393 (53 SiO₂, 6 Na₂O, 12 K₂O, 5 MgO, 20 CaO, 4 P₂O₅ wt%) [4], which are extensively applied in bone tissue engineering. Beyond silicate glasses, borate and borosilicate glasses have gained increasing interest in biomedical and technological applications [5–7]. When exposed to biological environments, bio-glasses undergo chemical degradation, forming a hydroxyapatite (HA) layer that enhances bonding between bone and tissue [8]. Among these, borate-based glasses offer a more controllable degradation rate for HA formation compared to silicate glasses [9,10], making them promising candidates for future applications.

1393 bioactive glass demonstrates strong bonding with both hard and soft tissues and has been shown to promote osteogenesis through the activation of relevant genes [11]. Boron, naturally present in trace amounts in the human body [12], can act as a catalyst for novel biological behaviors and has potential in pharmaceutical drug design. Boron-containing bioactive molecules are generally categorized into two types: those containing a single boron atom and those forming boron clusters. In the present study, 1393 bioactive glass was used as a reference. The aim of this work is to evaluate XRD patterns, density, and destructive mechanical properties such as microhardness, compressive strength, and flexural strength. Non-destructive tests were performed using ultrasonic wave velocity measurements to study elastic properties, including Young’s modulus, shear modulus, bulk modulus, and Poisson’s ratio.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Composition and Preparation of Bioactive Glass

The weight percent compositions of the 1393 bio-glass samples are provided in Table 1. A base batch and four additional batches with varying raw material concentrations were prepared. Conventional melting and annealing techniques were employed. Fine-grained quartz was used as the SiO₂ source, while soda and lime were introduced as their respective anhydrous carbonates (Na₂CO₃ and CaCO₃). P₂O₅ was added as ammonium dihydrogen orthophosphate (NH₄H₂PO₄), and MgO and K₂O were incorporated as MgCO₃ and K₂CO₃, respectively. Boron trioxide (B₂O₃) was used directly as a source of boron.

The weighed raw materials were mixed for 30 minutes and melted in alumina crucibles. The thermal cycle for all glass samples was set as follows: room temperature to 1000 °C at 10 °C/min, held at 1000 °C for 1 hour, ramped to 1400 °C at 10 °C/min, and maintained at 1400 °C for 2 hours. Melting was performed in an electronic global furnace under an air atmosphere. The molten glass was poured onto a preheated aluminum sheet and transferred to a controlled muffle furnace at 450 °C for annealing. After 1 hour, the furnace was cooled to room temperature at 15 °C/h. Finally, the glass samples were ground in an agate jar to produce powders for subsequent characterization and measurements.

Table-1 Composition of Bioactive Glass (weight %)

| SiO2 | Na2O | CaO | P2O5 | MgO | K2O | B2O3 | |

| 1393 | 53 | 6 | 20 | 4 | 5 | 12 | 0 |

| G-1 | 39.75 | 6 | 20 | 4 | 5 | 12 | 13.25 |

| G-2 | 26.5 | 6 | 20 | 4 | 5 | 12 | 26.5 |

| G-3 | 13.25 | 6 | 20 | 4 | 5 | 12 | 39.75 |

| G-4 | 0 | 6 | 20 | 4 | 5 | 12 | 53 |

2.2X-ray diffraction measurements

The bioactive glass samples were ground into a fine powder with a particle size of 75 µm for X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis. XRD was performed to identify and characterize the phases present in the glass, which is inherently amorphous. A RIGAKU Miniflex II diffractometer equipped with Cu-Kα radiation (λ = 1.5405 Å), operating at a tube voltage of 40 kV and a current of 35 mA, was used. Measurements were carried out over a 2θ range of 20° to 80°, with a step size of 0.02° and a scanning speed of 1° per minute. JCPDS data cards were employed as reference standards for peak identification.

2.3 Density measurement

The densities of all samples were measured at room temperature using a digital balance (Satorius, Model- BP221S, USA) which has an accuracy of ±0.0001 gm. Water was used as an immersion fluid. Density was determined by Archimedes principle using the following formula.

Density =[Wair/ (Wair-Wwater)] x 0.988

Where, ‘W’air is the weight in air, ‘Wwater’ is the weight in water and density of water is 0.988.

2.4 Measurement of Mechanical Properties

Flexural Strength

The bioactive glass samples were cast in cubical shape and were ground and polished to get the desired size of 1cm x 1cm x 1cm. These samples were subjected to three point bending test at room temperature using an Instron Universal Testing Machine (AGS 10kND, SHIMADZU) whose cross- head speed was 0.5 mm/min bearing a full scale load of 2500 kg. The calculation of flexural strength was calculated using the formula.

F = (3Pf L) / (2bh2)

Where ‘Pf’ is the load and ‘L’, ‘b’, ‘h’ are the length, breadth and height of the glass samples respectively.

Compressive Strength

For measuring compressive strength of the bioactive glass samples the Kinston Universal Testing Machine was used having a cross-speed of 0.05 cm/min and full scale load of 2500 kg. The samples were cut into the desired size of 2cm x 2cm x 1cm according to ASTM standard D3171 and the test was conducted at room temperature.

Hardness :-The hardness of specimens having size of 1cm x 1cm x 1cm according were mesured to ASTM standard C730-98 using the Hardness Testing Machine. Indentations were made on the samples with loads lying within the range of 30mN – 2000mN which were applied at a velocity of 0.1 cm/sec. Formula for calculation of micro hardness (GPa) is given as belong.

H = 1.854 x (P/d2)

Where ‘P’ is the load and‘d’ is the diagonal of the indentation.

2.5 Elastic Properties

The 1393 and SiO2 replace by boron trioxide (B2O3) in 1393 bioactive glass samples were cut and polished into cubic pieces and placed inside the instrument Olympus (M-45, USA) for measuring the ultrasonic wave velocities. Sonfech shear gel and Couplant glycerin were used for measuring the shear and longitudinal wave velocities respectively. Various formulae involving these velocities and density values were used for the calculation of Poisson’s Ratio, Young’s, Shear and Bulk Modulus of elasticity.

Young’s modulus (E) = ρ VL2 [(1+d) (1-2d) / (1-d)],d= Poisson’s Ratio

VL= longitudinal velocity, VT= Shear velocity

Shear Modulus (G) = VT2 ρ , ρ= density

Bulk modulus (K) = E/3(1-2d) , E= Young’s modulus

Poisson’s Ratio = [1-2(VT /VL)2] / [2-2(VT /VL)2]

3. Results and discussion

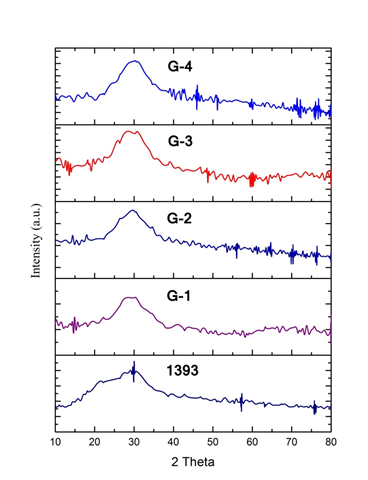

3.1 X-Ray analysis of bioactive glasses The XRD patterns of the base glass and the SiO₂-replaced samples with boron trioxide (B₂O₃) in the 1393 bioactive glass are presented in Figure 1. The results confirm the amorphous nature of the glass, as evidenced by the absence of sharp peaks, indicating no crystalline phases are present. A broad hump is observed in the 2θ range of 25° to 35°, which becomes more pronounced with increasing B₂O₃ content. This is the only noticeable change across the different patterns and indicates that boron trioxide (B₂O₃) is completely incorporated into the glass matrix

Figure:-1- X-RD 1393 &SiO2 replace by boron trioxide (B2O3) bioactive glass sample

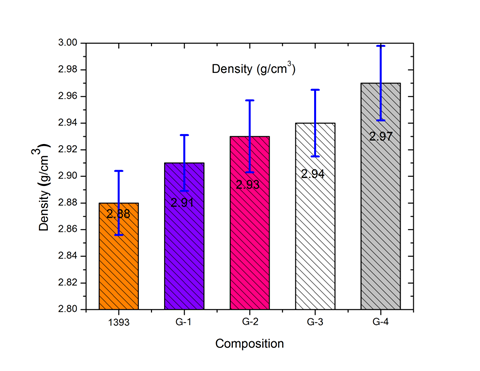

3.2 Density Measurements of 1393, G-1, G-2, G-3 and glass samples The variation in density, measured using Archimedes’ principle, is shown in Figure 2. It clearly indicates that replacing SiO₂ with boron trioxide (B₂O₃) in the 1393 bioactive glass sample causes only a slight increase in density, from 2.88 to 2.97 g/cm³. This minor change is attributed to the similar densities of SiO₂ and B₂O₃. Borate-based glass is generally considered to exhibit a contracting volume behavior. Additionally, density depends on particle size, and as the particle size increases, the incorporation of B₂O₃ in the 1393 bioactive glass sample leads to a slight increase in density.

Figure 2- Density of 1393, G-1, G-2, G-3 and G-4 glass samples

3.3 Mechanical Properties of 1393, G-1, G-2, G-3 and glass samples

Flexural strength

Figure 3 shows the results of the flexural strength of 1393 is [44.45], G-1[57.24], G-2[58.41], G-3[62.49] and G-4[66.55] M-Pa samples. The results show an increasing tendency in flexural strength as the percentage of boron trioxides (B2O3) is increases in 1393 bioactive glass sample replace SiO2. This increase may be due to the B3+ may act as network intermediate, thus more the compactness of glass structure [13].

Compressive strength

Figure 4 shows the results of the compressive strength of 1393 is [69.82], G-1 [78.63], G-2 [81.35], G-3 [79.15] and G-4[84.13] M-Pa samples. The results show an increasing tendency in compressive strength as the percentage of boron trioxides (B2O3) is increases in 1393 bioactive glass sample replace SiO2. This increase may be due to the B3+ may act as network intermediate, thus more the compactness of glass structure [13].

Figure 3- Flexural strength of 1393, G-1, G-2, G-3 and G-4 glass samples

Micro Hardness

Figure 5 shows the results of the Micro Hardness of 1393 is [5.45], G-1 [5.58], G-2 [5.61], G-3 [5.87] and G-4 [6.09] M-Pa samples. The results show an increasing tendency in Micro Hardness

Figure 4- Compressive strength of 1393, G-1, G-2, G-3 and G-4 glass samples

Figure 5- Micro Hardness of 1393, G-1, G-2, G-3 and G-4 glass samples

As the percentage of boron trioxides (B2O3) is increases in 1393 bioactive glass sample replace SiO2. This increase may be due to the B3+ may act as network intermediate, thus more the compactness of glass structure [13].As in the present study there has been a gradual addition of 0-1.53 weight % of B3+ ions it acted as an intermediate and made the glass structure more compact. This justifies the changing trend in the mechanical properties.

3.4 Elastic Properties

The elastic properties specifically Poisson’s Ratio, Young’s, Shear and Bulk modulus of 1393 G-1 ,G-2, G-3, and G-4 glasses sample were calculated using the longitudinal and shear ultrasonic wave velocities. These values were having graphically represented in Figure 6 (a),(b),(c),(d) There is an increase in values of Young’s, shear and bulk modulus with increase in B3+ concentration whereas a slight decreasing trend in values is observed for Poisson’s ratio. Increase in elastic modulus values have been earlier reported by Gaafar and Kannapan [14, 15] which was ascribed to the increase in connectivity in the glass network. However the slight reduction in Poisson’s ratio could have been due to change in the type of bonding in the glass structure on addition of boron trioxides (B2O3)[16].

Figure 6- Elastic properties of 1393, G-1, G-2, G-3 and G-4 glass samples

CONCLUSION

In the present study, various properties of bioactive glass samples G-1, G-2, G-3, and G-4, in which SiO₂ was partially replaced by boron trioxide (B₂O₃), were investigated. XRD analysis confirmed the amorphous nature of all the glass samples. Mechanical properties, including bending strength, compressive strength, and hardness, as well as elastic properties such as Young’s modulus, bulk modulus, and shear modulus, showed an increasing trend with higher concentrations of B₂O₃ in the bioactive glass. In contrast, Poisson’s ratio exhibited a slight decrease upon B³⁺ addition. Overall, the results indicate that bioactive glasses with partial substitution of SiO₂ by B₂O₃ possess enhanced mechanical and elastic properties, suggesting their potential suitability as biomaterials for biomedical applications.

References

- L. L. Hench, Journal of Material Science and Material Medicine,17, 967–978(2006).

- H. O. Ylänen, Bioactive glasses Materials, properties and applications. Woodhead Publishing Limited, (2011).

- L. LHench,.Bioceramics: From concept to clinic. J. Am. Ceram.Soc., 74 (7), 1487−1510 (1991).

- M. NRahaman. D. E Day, B. S Bal,.Q. Fu, S. B Jung,L. F.Bonewald and A. P Tomsia,Bioactive glass in tissue engineering.ActaBiomater.,7 (6), 2355−2373 (2011).

- Y. Yun, P. Bray, Nuclear magnetic resonance studies of the glasses in the system Na2O–B2O3–SiO2, J. Non-Cryst. Solids,27 (3),363–380(1978).

- Q.Z. Chen, I.D. Thompson and A.R. Boccaccini, 45S5 Bioglass®-derived glass–ceramic scaffolds for bone tissue engineering, Biomaterials,27 (11) 2414–2425(2006).

- T. Kokubo, H. Takadama, How useful is SBF in predicting in vivo bone bioactivity? Biomaterials, 27 (15), 2907–2915 (2006).

- W. Cao and L.L. Hench, Bioactive materials, Ceram. Int. ,22 (6) 493–507(1996).

- H. Fu, Q. Fu, N. Zhou,W. Huang, M.N. Rahaman, D.Wang and X. Liu, In vitro evaluation of borate-based bioactive glass scaffolds prepared by a polymer foam replication method, Mater. Sci. Eng., C,29 (7) 2275–2281(2009).

- T. Furukawa and W.B. White, Structure and crystallization of glasses in the Li2 Si2O5–TiO2 system determined by Raman spectroscopy, Phys. Chem. Glasses,20 (4), 69–80(1979).

- L. L Hench, Genetic design of bioactive glass. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc., 29 (7), 1257−1265 (2009).

- Emsley J. Nature’s Building Blocks: An AZ Guide to the Elements. Oxford University Press; Oxford, UK: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- A.K.Srivastava Journal of Materials Science Research, Vol.No.2: Aprial 2012.

- M. S. Gaafar, S. Y. Marzouk, H. A. Zayed, L. I. Soliman andA. H. Serag El-Deen, Curr. Appl. Phys.,13, 152-158 (2013).

- A. N. Kannappan, S. Thirumaran and R. Palani, ARPN J. Eng. Appl. Sci., 4, 27-31 (2009).

- M. S. Gaafar, F. H. ElBatal, M. ElGazery and S. A. Mansour,Acta Phys. Polonica A, 115, 671-678 (2009).