Introduction: Paddy is the largest food crop globally, producing not only rice but also significant amounts of waste known as rice husk (RH). RH is generated as a byproduct during rice processing, with an estimated annual production of approximately 545 million tons. However, much of this RH remains underutilized, particularly in Indonesia, one of the world’s leading rice producers. Commonly, RH is burned to generate heat, but this practice contributes to air pollution. Another potential use of RH is as an animal feed supplement, although its production is still limited and primarily applied in small-scale farming areas.

The chemical composition of RH varies depending on factors such as paddy variety, climate, geographic location, soil chemistry, sample preparation, and analytical methods. Silica content in RH was first reported in 1938, and since then, numerous efforts have been made globally to synthesize silica from RH. Rice husk ash (RHA) is recognized as a valuable source for producing high-quality silica.

Industrial-scale silica production typically involves mechanical, physical, chemical, or high-temperature processes that often require large amounts of acids, resulting in significant effluent generation. Silicon dioxide (SiO₂), or silica, is a versatile material widely used across industries, including rubber, fertilizers, concrete fillers, food, pharmaceuticals, pesticides, paints, membranes, electronics, and ceramics.

According to Riveroz and Garza, compared to other silica sources such as bentonite, rice husk contains lower levels of contaminants, which is critical for high-performance applications, such as in solar cell materials. At temperatures below 700 °C, RHA rich in amorphous silica can be obtained. However, RHA may also contain metal contaminants like Fe, Na, K, and Ca, which can reduce silica purity and surface area. In plants, silicon is absorbed from soil water as water-soluble silicic acid and plays a vital physiological role, including helping plants cope with biotic and abiotic stress.

In this study, we focus on synthesizing nanosilica from waste rice husk using a simple, efficient method and evaluating the resulting products. To the best of our knowledge, few industrial-scale nanosilica producers utilize rice husk as a raw material. This work aims to contribute to the development of sustainable nanosilica production from RHA at an industrial scale in the near future.

EXPERIMENTALS

Rice husk (RH) used as the source of nanosilica was collected from rice mills in West Java, Indonesia. The RH was used directly without any special pre-treatment. It was initially burned at 300 °C for 1 h to produce rice husk ash (RHA), which appeared black in color. The RHA was then treated with 1 N HCl and stirred on a hotplate at 80 °C for 1 h. To assess the effect of acid treatment, a control sample was also prepared without the addition of acid. The mixtures were allowed to stand at room temperature for 24 h and subsequently dried in an oven at 110 °C for 2 h.

The dried samples were further sintered in a furnace at different temperatures—600 °C, 700 °C, and 800 °C—to study the effect of heat treatment. This process resulted in a white nanosilica powder.

The obtained nanosilica samples were characterized using several techniques. X-ray diffraction (XRD) was employed to determine the structure and phase of the nanosilica, distinguishing between crystallite and amorphous phases. Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) was used to identify the chemical bonds present in the samples, while scanning electron microscopy (SEM) was applied to examine the surface morphology. The particle size of the nanosilica was estimated using the intercept method, as described below.

Where is the average diameter of particles, LT is the total length of lines, P is the number line intersection and M is magnification.

RESULT AND DISCUSSION

XRD pattern

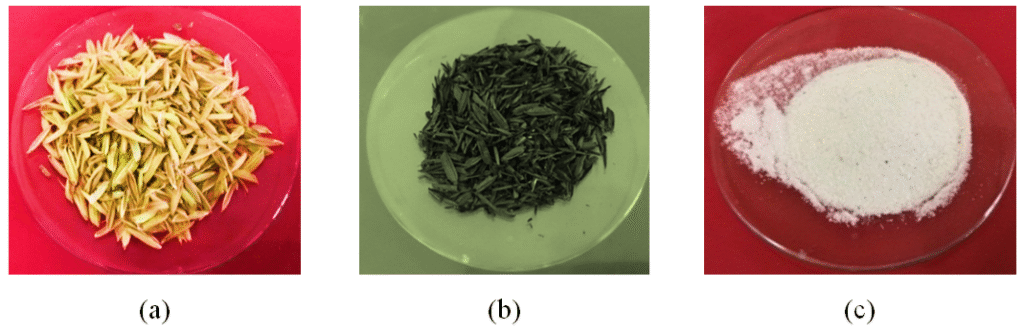

Figure 1 illustrates the differences in shape and color among the RH (a), RHA (b), and nanosilica (c) samples. Raw rice husk (RH), the outer covering of the rice grain, appears yellow. Upon heating at 300 °C for 1 hour, the RH was converted into rice husk ash (RHA), which turned black, indicating the presence of carbon. The RHA exhibited a brittle texture, making it easy to break down. Subsequent acid and heat treatments produced a white nanosilica powder, which was ready for further analysis.

Figure 1. Raw RH sample (a), RHA sample (b), and the resulting nanosilica (c).

Figure 2 presents the XRD patterns of nanosilica synthesized at 600, 700, and 800 °C. All samples showed similar diffraction patterns, with a broad peak observed at 2θ values ranging from 16° to 26°, indicating the amorphous nature of the synthesized nanosilica.

The XRD pattern indicates the formation of amorphous nanosilica, with no additional peaks detected, confirming that the nanosilica was produced free of impurities. Amorphous nanosilica is particularly advantageous for industrial applications because it can be easily transformed into other products, such as zeolites. Typically, an amorphous nanosilica structure forms at synthesis temperatures below 800 °C. Previous studies have reported that cristobalite silica is produced at around 800 °C. However, in our study, amorphous nanosilica was still obtained at this temperature. This enhanced stability is attributed to the addition of acid during the preparation process, which effectively removes unwanted elements from the silica.

As shown in Figure 3, the XRD patterns of acid-treated and non-acid-treated samples synthesized at 800 °C were compared. The sample prepared without acid treatment exhibits crystalline peaks between 2θ = 22° and 36°, indicating the presence of cristobalite silica. This crystallization may be due to contaminants such as aluminum or carbon.

which naturally exists in RH. These contaminants can be removed by adding an acid solution. The acid will react with the contaminants and will be disappeared during the heating process due to evaporation. It is worthy to note that acid treatment is necessary to produce high-quality nanosilica from RH.

FTIR analysis To identify the molecular bonds in the nanosilica samples, FTIR spectroscopy was employed. The FTIR spectrum of the samples is shown in Figure 4. Two prominent peaks appear at 820 cm⁻¹ and 564 cm⁻¹, corresponding to the asymmetric stretching vibrations of Si–O–Si within the SiO₄ tetrahedron and the symmetric stretching of Si–O (silanol) bonds, respectively. Additionally, a smaller peak at 1996 cm⁻¹ was observed, indicating the presence of O–H bonds from adsorbed water on the nanosilica surface. These results confirm the successful synthesis of high-purity nanosilica. A comparable FTIR spectrum for nanosilica was also reported by Bui Du et al.

Figure 4. FTIR spectrum of nanosilica synthesized at temperature of 600, 700 and 800 °C.

SEM analysis

The surface of nanosilica samples was captured by FE-SEM as displayed in figure 5. At temperature of 600 °C and 700 °C, the shape and size of the particle were not uniform. The smaller particles were attached to the surface of the bigger particles. However, at temperature of 800 °C, the size of small particles is quite uniform with an estimated diameter about 12 nm using equation (1). Lu and Hsieh stated that due to the non-conductive property of nanosilica, the charges are quickly accumulated on the surface of powder and the aglomeration of particles are easily occured18.

Simultaneous Thermal Analysis (STA)

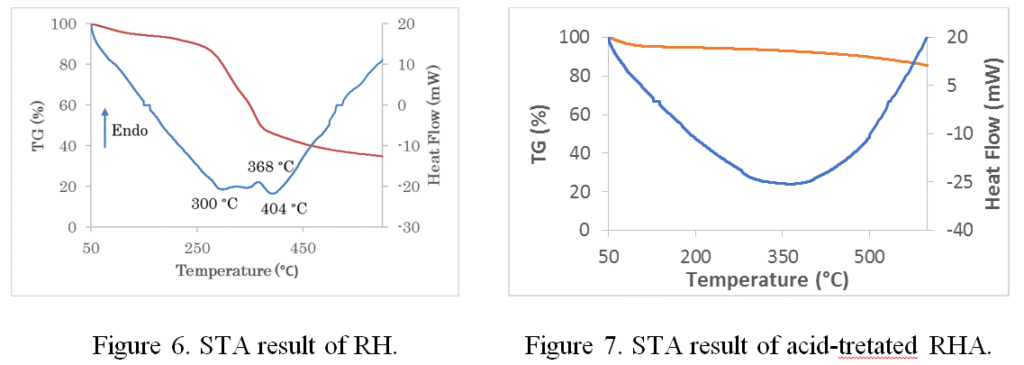

The temperature has an important role during the synthesis process of nanosilica from RH. In order to observe the effect of temperature on the formation of nanosilica, we applied STA technique for two samples RH and acid treated RHA. Figure 6 shows STA result of RH sample that exhibited drastically loss of mass about 60% at temperature about 300 °C. This might be caused by adserbed water and other molecules were evaporated. The heatflow graph showed the exothermic reaction at 300 °C due to adsobed water was evaporated while endothermic reaction occurred at 368 °C might be caused by the burning of carbon contaminants. Another exothermic reaction was observed at 404 °C which indicated the phase transformation and amorphous nanosilica started to form.

Figure 7 shows STA result of acid-treated- RHA and the mass has changed only 10% for entire analysis temperature from 50 to 600 °C. This result indicated that most of adsorbed water and contaminats were succesfully removed after adding acid solution. In addition, there is no peak in heat flow graph meaning the nanosilica has no impurities such as carbon and other elements.

CONCLUSION

Nanosilica was successfully synthesized from waste rice husk (RH) using a simple heating method. The resulting white powder of amorphous nanosilica was confirmed by XRD and FTIR analyses. SEM images revealed that the nanosilica prepared at 800 °C exhibited a uniform shape and size; however, some agglomeration was observed, likely due to the non-conductive nature of the material. The estimated particle diameter was approximately 12 nm. STA analysis highlighted the influence of temperature on the preparation process. Furthermore, both XRD and STA results demonstrated that acid treatment of rice husk ash (RHA) is crucial for obtaining high-quality amorphous nanosilica free from contaminants.

References

- Rafiee, E.; Shahebrahimi, S.; Feyzi, M.; Shaterzadeh, M. Int. Nano Let.2012, 2:29, 1-8.

- Martín, J.I. The desilicification of rice hulls and a study of the products obtained, Lousiana State University, 1938.

- Umeda, J.; Kondoh, K. Indust. Crops and Prod. 2010, 32, 539-544.

- Pijarn, N.; Jaroenworaluck, A.; Sunsaneeyametha, W.; Stevens, R. Powd. Tech. 2010, 203(3), 462-468.

- Fernandes, I.J.; Calheiro, D.; Sánchez, F.A.L.; Camacho, A.L.D.; Rocha, T. L. A. d. C.; Moraes, C.A.M.; d. Sousa, V. C. Mat. Res. 2017, 20, 512-518.

- Haus, R.; Prinz, S.; Priess, C. in Quartz: Deposits, Mineralogy and Analytics, eds. J. Götze and R. Möckel, Springer Berlin Heidelberg, Berlin, Heidelberg, 2012, pp. 29-51.

- Quercia, G.; Lazaro, A. Geus, J.W.; Brouwers, H.J.H. Cem. and Conc. Comp. 2013, 44, 77-92.

- Bernardos, A.; Kouřimská, L. Czech J. Food Sci., 2013, 31, 99-107.

- Tang, L.; Cheng, J. Nano Today. 2013, 8(3), 290‐312.

- Yazdimamaghani, M.; Pourvala, T.; Motamedi, E.; Fathi, B.; Vashaee, D.; Tayebi, L. Materials. 2013, 6, 3727-3741.

- Carneiro, C.; Vieira, R.; Mendes, A.M.; Magalhães, F.D. J. of Coat. Tech. and Res. 2012, 9, 687–693.

- Tolba, G.M.K.; Bastaweesy, A.M.; Ashour, E.A.; Abdelmoez, W.; Khalil, K.A.; Barakat, N.A.M. Arab. J. of Chem. 2016, 9, 287-296.

- Mukherjee, D.P.; Das, S.K. J. of Non-Cryst. Sol. 2013, 368, 98-104.

- Riveros, H.; Garza, C. Rice husks as a source of high purity silica, Journal of Crystal Growth 75 (1986) 126-131.

- Dominic, C.D.M.; Begum, P.M.S.; Joseph, R.; Joseph, D.; Kumar, P.; Ayswarya, E.P. Inter. J. of Sci., Envi. and Tech. 2013, 2, 1027–1035.

- Akhayere, E.; Kavaz, D.; Vaseashta, A. Polish J. of Envi. Stud. 2019, 28(4), 2513-2521.

- Tuan, L.N.A.; Dung, L.T.K.; Ha, L.D.T.; Hien, N.Q.; Phu, D.V.; Du, B.D. Viet. J. of Chem. 2017, 55(4), 455-459.

- Lu, P.; Hsieh, Y.-L. Powd. Tech. 2012, 225, 149-155.