Introduction: The development of inexpensive, sustainable, and environmentally friendly catalysts for organic transformations has become a topic of significant importance in modern organic synthesis. Traditional catalytic methodologies often rely heavily on precious metals, such as palladium, platinum, and rhodium, which, despite their high efficiency, are expensive, scarce, and environmentally challenging. In contrast, the use of earth-abundant and main-group elements as catalysts has remained relatively underexplored and underdeveloped in comparison to their transition-metal counterparts.¹

Moreover, many existing catalytic systems are dominated by complexes stabilized through bulky and sophisticated ligands.²a-c The synthesis of such ligand-supported complexes is typically labor-intensive, costly, and time-consuming, which further limits their practical utility on an industrial scale. Therefore, there is a pressing need to design and develop catalytic systems that are not only highly efficient but also environmentally benign, cost-effective, and derived from readily available main-group elements.

Among the main-group elements, iodine and its compounds hold particular interest due to their versatile chemistry and wide range of industrial applications. Approximately 16% of global iodine production is consumed in catalytic processes. A notable example is the Monsanto–Cativa process for the large-scale production of acetic acid, where hydroiodic acid (HI) plays a crucial role as a co-catalyst. In this process, HI converts methanol into methyl iodide, which subsequently undergoes carbonylation to form acetyl iodide. The latter, upon reaction with water, regenerates HI and produces acetic acid as the final product. This cycle highlights iodine’s efficiency as a sustainable catalytic mediator. Beyond this, iodine-based compounds have also found applications in polymer synthesis, the food industry, pharmaceuticals, and medicinal chemistry, further emphasizing their industrial relevance.²d

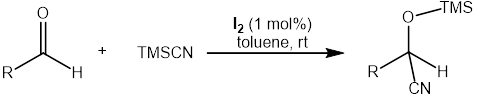

One transformation of great significance in synthetic organic chemistry is the cyanosilylation of carbonyl compounds, particularly aldehydes. This reaction produces cyanohydrins, which are highly valuable intermediates in both academic and industrial settings. Cyanohydrins serve as precursors for the synthesis of a wide variety of important molecules, including β-amino alcohols, α-amino acids, and α-hydroxy acids, all of which are key motifs in pharmaceuticals, natural products, and fine chemicals. The synthesis of cyanohydrins was first described by Wöhler and Winkler in the 19th century, using hydrogen cyanide (HCN) as the cyanide source.³˒⁴ However, due to the extreme toxicity, volatility, and handling difficulties associated with HCN, its use in practical synthesis is highly restricted.

To overcome these limitations, safer and more convenient cyanating agents have been developed. Among them, trimethylsilyl cyanide (TMSCN) has emerged as the most widely used reagent, owing to its ease of handling, reduced toxicity compared to HCN, and high efficiency in cyanohydrin formation. Over the past few decades, the cyanosilylation of carbonyl compounds using TMSCN has attracted considerable attention, especially in the case of aldehydes. In particular, catalytic methods employing main-group elements have been increasingly explored as sustainable alternatives to traditional transition-metal-catalyzed protocols.⁵–⁷

Despite these advances, iodine-based catalytic systems for cyanosilylation remain surprisingly underexplored. Iodine is earth-abundant, inexpensive, environmentally benign, and readily available, making it an attractive candidate for sustainable catalysis. To the best of our knowledge, no direct reports exist on the use of elemental iodine (I₂) as a catalyst for the cyanosilylation of aldehydes. Therefore, in this study, we aimed to investigate the catalytic utility of molecular iodine (I₂) in promoting the cyanosilylation of aldehydes under mild conditions. Our findings suggest that iodine may serve as an effective and green alternative to traditional metal-based catalysts, thereby expanding the scope of main-group catalysis in organic transformations.

Experimental Section

All solid aldehydes were employed without further purification, while liquid aldehydes were distilled prior to use. Trimethylsilyl cyanide (TMSCN) was freshly distilled before application. Tetrahydrofuran, hexane, and toluene were used as received without additional purification.

^1H and ^13C NMR spectra were recorded in CDCl₃ on a Bruker 300 MHz spectrometer. Chemical shifts are reported in parts per million (ppm) relative to tetramethylsilane (TMS) as an internal standard.

For a typical reaction, aldehydes (1 mmol) and TMSCN (1.2 mmol) were dissolved in toluene, followed by the addition of iodine (I₂). The mixture was placed in a vial equipped with a magnetic stir bar and stirred at room temperature. Reaction progress was monitored by ^1H NMR spectroscopy. Upon completion, the volatile components were removed under reduced pressure to afford the desired cyanosilylated product without further purification. All ^1H and ^13C NMR spectra of the products were consistent with those reported in the literature.⁸

NMR Data for Cyanosilylated Products

Entry 2, Table 1:

^1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl₃): δ 0.27 (s, 9H, Si(CH₃)₃), 5.54 (s, 1H, OCHCN), 7.42–7.52 (m, 5H, ArH).

^13C{^1H} NMR (75 MHz, CDCl₃): δ –0.21 (Si(CH₃)₃), 63.69 (OCHCN), 119.25 (CN), 126.40, 128.98, 129.39, 136.30 (ArC).

Entry 1, Table 2:

^1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl₃): δ 0.19 (s, 9H, Si(CH₃)₃), 1.02–1.07 (t, J = 6 Hz, 3H, CH₃), 1.75–1.85 (m, 2H, CH₂), 4.35 (t, J = 6 Hz, 1H, CHOSi(CH₃)₃).

^13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl₃): δ –0.30 (SiMe₃), 9.06, 29.78, 62.81, 120.05 (CN).

Entry 2:

^1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl₃): δ 0.22 (s, 9H, Si(CH₃)₃), 0.98 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 3H, CH₃), 1.42–1.54 (m, 2H, CH₂), 1.71–1.84 (m, 2H, CH₂), 4.31 (t, J = 6 Hz, 1H, CHOSi(CH₃)₃).

^13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl₃): δ –0.35 (SiMe₃), 13.35, 19.00, 38.98, 61.81, 120.18 (CN).

Entry 3:

^1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl₃): δ 0.31 (d, J = 2.4 Hz, 9H, Si(CH₃)₃), 5.16 (d, J = 6 Hz, 1H, OCHCN), 6.23 (m, 1H, CH=CH), 6.86 (d, J = 15.6 Hz, 1H, CH=CH), 7.34–7.46 (m, 5H, ArH).

^13C{^1H} NMR (75 MHz, CDCl₃): δ –0.03 (Si(CH₃)₃), 62.33 (OCHCN), 118.49 (CN), 123.73, 127.06, 128.84, 128.87, 134.03, 135.17 (ArC).

Entry 4:

^1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl₃): δ 0.17 (s, 9H, SiMe₃), 7.17–7.54 (m, 4H, ArCH), 5.37 (s, 1H, CHOSi(CH₃)₃).

^13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl₃): δ –0.31 (SiMe₃), 62.81 (OCH), 118.62 (CN), 124.80, 128.30, 130.47, 132.31, 137.27 (ArC).

Entry 5:

^1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl₃): δ 0.29 (s, 9H, Si(CH₃)₃), 6.23 (s, 1H, CHOSi(CH₃)₃), 7.61 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H, Ph), 7.78 (t, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H, Ph), 8.04 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H, Ph), 8.17 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H, Ph).

^13C{^1H} NMR (75 MHz, CDCl₃): δ –0.30 (Si(CH₃)₃), 60.27 (CHOSi(CH₃)₃), 117.97 (CN), 125.40, 128.60, 130.33, 132.00, 134.60, 146.48 (ArC).

Entry 6:

^1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl₃): δ 0.20 (s, 9H, Si(CH₃)₃), 5.69 (s, 1H, CHOSi(CH₃)₃), 7.00 (t, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H, CH), 7.31 (d, J = 6.0 Hz, 1H, CH), 7.32 (d, J = 6.0 Hz, 1H, CH).

^13C{^1H} NMR (75 MHz, CDCl₃): δ –0.10 (Si(CH₃)₃), 60.12 (CHOSi(CH₃)₃), 118.58 (CN), 127.43, 127.89, 128.23, 138.68 (ArC).

Entry 7:

^1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl₃): δ 0.25 (s, 9H, Si(CH₃)₃), 5.52 (s, 1H, CHOSi(CH₃)₃), 7.40–7.50 (m, 4H, Ph).

^13C{^1H} NMR (75 MHz, CDCl₃): δ –0.14 (Si(CH₃)₃), 63.71 (CHOSi(CH₃)₃), 119.25 (CN), 122.89, 126.40, 128.98, 129.22, 129.37, 136.38 (ArC).

Entry 8:

^1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl₃): δ 0.26 (s, 9H, Si(CH₃)₃), 5.50 (s, 1H, OCHCN), 7.41 (m, 4H, ArH).

^13C{^1H} NMR (75 MHz, CDCl₃): δ –0.23 (Si(CH₃)₃), 63.05 (OCHCN), 118.88 (CN), 127.27, 129.22, 135.01, 135.38 (ArC).

Entry 9:

^1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl₃): δ 0.26 (s, 9H, Si(CH₃)₃), 5.47 (s, 1H, CHOSi(CH₃)₃), 7.37 (d, J = 8 Hz, 2H, Ar-H), 7.57 (d, J = 8 Hz, 2H, Ar-H).

^13C{^1H} NMR (75 MHz, CDCl₃): δ –0.25 (Si(CH₃)₃), 63.04 (CHOSi(CH₃)₃), 118.17 (CN), 123.49, 127.98, 132.14, 135.41 (ArC).

Entry 10:

^1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl₃): δ 0.21 (s, 9H, Si(CH₃)₃), 5.76 (s, 1H, CHOSi(CH₃)₃), 7.02 (t, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H, CH), 7.37 (d, J = 6.0 Hz, 1H, CH), 7.39 (d, J = 6.0 Hz, 1H, CH).

^13C{^1H} NMR (75 MHz, CDCl₃): δ –0.08 (Si(CH₃)₃), 59.615 (CHOSi(CH₃)₃), 118.37 (CN), 126.43, 127.23, 139.60 (ArC).

Entry 11:

^1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl₃): δ 0.25 (s, 9H, Si(CH₃)₃), 2.39 (s, 3H, CH₃), 5.49 (s, 1H, CHOSi(CH₃)₃), 7.23 (d, J = 7.5 Hz, 2H, Ph), 7.39 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H, CH).

^13C{^1H} NMR (75 MHz, CDCl₃): δ –0.08 (Si(CH₃)₃), 21.21 (CH₃), 63.61 (CHOSi(CH₃)₃), 119.36 (CN), 126.44, 129.62, 133.50, 139.37 (ArC).

Entry 12:

^1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl₃): δ 0.21 (s, 9H, Si(CH₃)₃), 3.81 (s, 3H, CH₃), 5.42 (s, 1H, CHOSi(CH₃)₃), 6.90 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H, Ph), 7.38 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 2H, CH).

^13C{^1H} NMR (75 MHz, CDCl₃): δ 55.49 (OCH₃), 63.51 (CHOSi(CH₃)₃), 119.48 (CN), 114.43, 128.08, 128.65, 160.51 (ArC).

Results and Discussion

The study was initiated by examining the cyanosilylation of benzaldehyde (1 mmol) with TMSCN (1.2 mmol) in the presence of iodine as a catalyst. Optimization of the reaction was performed by varying parameters such as reaction time and solvent.

Initially, the reaction was carried out using 1 mol% iodine in THF, which afforded a 95% conversion (Table 1, entry 1). When the reaction was performed in toluene, benzaldehyde underwent cyanosilylation with 99% conversion within 20 minutes (Table 1, entry 2). In the case of hexane, 90% conversion was achieved within the same reaction time (Table 1, entry 3). In contrast, the blank reaction of benzaldehyde with 1.2 equivalents of TMSCN, in the absence of a catalyst, resulted in only 35% conversion even after 1 hour (Table 1, entry 4).

From these observations, it can be concluded that the optimal conditions for the cyanosilylation of aldehydes involve 1 mol% iodine as the catalyst and 1.2 equivalents of TMSCN in THF.

Table 1. Optimization of reaction conditions

| Entry No. | Catalyst | Solvent | Time (min) | Conversions (%) |

| 1. | I2 | THF | 20 | 95 |

| 2. | I2 | Toluene | 20 | 99 |

| 3. | I2 | Hexane | 20 | 90 |

| 4. | – | Toluene | 60 | 35 |

Using the optimized parameters, this protocol was successfully applied to the cyanosilylation of a broad range of aldehydes. As summarized in Table 2, all examined aldehydes underwent complete conversion within 10–60 minutes when employing only 1 mol% of the catalyst. Aliphatic aldehydes were well tolerated and exhibited excellent reactivity under the standard conditions; for example, propionaldehyde, n-butyraldehyde, and cinnamaldehyde achieved 99%, 99%, and 97% conversion, respectively, within just 15 minutes (Table 2, entries 1–3). Aromatic aldehydes bearing electron-withdrawing substituents such as 3-nitrobenzaldehyde and 2-nitrobenzaldehyde also displayed remarkable activity, delivering 99% and 98% conversion, respectively, in 15 minutes (Table 2, entries 4–5). Under similar conditions, heteroaromatic aldehydes including 2-furaldehyde and 2-thiophenecarboxaldehyde afforded conversions of 95% and 99%, respectively, within 20 minutes (Table 2, entries 6, 10). Aldehydes substituted with halogens on the aromatic ring—such as 2-bromo-, 4-chloro-, and 4-bromobenzaldehyde—were smoothly transformed into the corresponding products with excellent conversions of 98%, 99%, and 99%, respectively, within 20 minutes (Table 2, entries 7–9). By contrast, substrates containing electron-donating groups (–Me, –OMe) required somewhat longer reaction times; for instance, 4-methylbenzaldehyde and 4-methoxybenzaldehyde both reached 99% conversion within 60 minutes at room temperature.

Table 2.Cyanosilylation of aldehydes catalyzed by Iodine.

| Entry | Substrate | Catalyst (mol%) | Time (min) | Conversion % |

| 1 | Propionaldehyde | 1 | 10 | 99 |

| 2 | n-Butyraldehyde | 1 | 10 | 99 |

| 3 | Cinnamaldehyde | 1 | 10 | 97 |

| 4 | 3-Nitrobenzaldehyde | 1 | 15 | 99 |

| 5 | 2-Nitrobenzaldehyde | 1 | 15 | 98 |

| 6 | 2-furaldehyde | 1 | 20 | 95 |

| 7 | 2-Bromobenzaldehyde | 1 | 20 | 98 |

| 8 | 4-Chlorobenzaldehyde | 1 | 20 | 99 |

| 9 | 4-Bromobenzaldehyde | 1 | 20 | 99 |

| 10 | 2-thiophenecarboxaldehyde | 1 | 20 | 99 |

| 11 | 4-Methylbenzaldehyde | 1 | 60 | 99 |

| 12 | 4-Methoxylbenzaldehyde | 1 | 60 | 99 |

| Conditions: Aldehydes (1 mmol), TMSCN (1.2 mmol), room temperature. Conversions of reactant to product were obtained by 1H NMR spectroscopy. | ||||

Conclusion

In conclusion, simple iodine serves as an efficient catalyst for the cyanosilylation of a broad range of aldehydes in toluene at room temperature. Key advantages include high catalytic efficiency with minimal catalyst loading, mild reaction conditions, wide substrate applicability, and excellent conversion rates.

References

1. (a) Su, B.; Cao, Z. C.; Shi, Z, J. Acc. Chem. Res. 2015, 48, 886−896. (b) King, A. E.; Stieber, S. C. E.; Henson, N. J.; Kozimor, S. A.; Scott, B. L.; Smythe, N. C.; Sutton, A. D.; Gordon,J. C. Eur. J. Inorg.Chem. 2016, 1635−1640. (c) Tamang, S. R.; Findlater, M. J. Org.Chem. 2017, 82, 12857−12862. (d) Chakraborty, S.; Guan, H. Dalton Trans. 2010, 39, 7427−7436.

2. (a) Chong, C. C.; Kinjo, R. ACS Catal.2015, 5, 3238−3259. (b) Liu, C.; Zhang, Y.; Qian, Q.; Yuan, D.; Yao, Y. Org. Lett. 2014, 16, 6172−6175. (c) Holzwarth, M. S.; Plietker, B.ChemCatChem 2013, 5, 1650−1679. (d) Kaiho, T. Iodine Chemistry and Applications

Wiley, Chichester, UK, 2014.

3. North, M.; Usanov D. L.; Young, C. Chem. Rev. 2008, 108,5146.

4. Winkler, F. W.; Liebigs, Ann. Chem.1832, 4, 242.

5. (a) Fu, Y.; Hou, B.; Zhao, X.; Du, Z.; Hu, Y. Chin. J. Org. Chem., 2015, 35, 2507; (b) Li, J.; Ren, Y.; Qi, C.; Jiang, H. Chem. Commun. 2017, 53, 8223; (c) Wang, F.; Wei, Y.; Wang, S.; Zhu, X.; Zhou, S.; Yang, G.; Gu, X.; Zhang, G.; Mu, X. Organometallics, 2015, 34, 86; (d) Kikukawa, Y.; Suzuki, K.; Sugawa, M.; Hirano, T.; Kamata, K.; Yamaguchi, K.; Mizuno, N. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed., 2012, 51, 3686.

6. (a) Evans, D. A.; Truesdale, L. K.; Carroll, G. L. J. Chem. Soc.,Chem. Commun. 1973, 55-56. (b) Lidy, W.; Sundermeyer, W. Chem. Ber. 1973, 106, 587-593. (c) Noyori, R.; Murata, S.; Suzuki, M. Tetrahedron 1981, 37, 3899-3910. (d) Greenlee, W. J.; Hangauer, D. G. Tetrahedron Lett. 1983, 24, 4559-4560. (e) Vougioukas, A. E.; Kagan, H. B. Tetrahedron Lett. 1987, 28, 5513-5516. (f) Reetz, M. T.; Drewes, M. W.; Harms, K.; Reif, W. Tetrahedron Lett. 1988, 29,3295-3298. (g) Faller, J. W.; Gundersen, L.-L. Tetrahedron Lett. 1993, 34, 2275-2278. (h) Scholl, M.; Fu, G. C. J. Org. Chem. 1994, 59, 7178-7179. (i) Cozzi, P. G.; Floriani, C. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 1 1995, 2557-2563. (j) Whitesell, J. K.; Apodaca, R. Tetrahedron Lett. 1996,

37, 2525-2528. (k) Yang, Y.; Wang, D. Synlett 1997, 1379-1380. (l) Komatsu, N.; Uda, M.; Suzuki, H.; Takahashi, T.; Domae, T.; Wada, M. Tetrahedron Lett. 1997, 38, 7215-7128. (m) Loh, T.-P.; Xu, K.-C.; Ho. D. S.-C.; Sim, K.-Y. Synlett, 1998, 369-370. (n) Saravanan, P.; Anand, R. V.; Singh, V. K. Tetrahedron Lett. 1998, 39, 3823-3824. (o) Bandini, M.; Cozzi, P. G.; Garelli, A.; Melchiorre, P.; Unami-Ronchi, A. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2002, 3243-3249. (p) King, J. B.; Gabbai, F. P. Organometallics 2003, 22, 1275-1280. (q) Cordoba, R.; Plumet, J. Tetrahedron Lett. 2003, 44, 6157-6159. (r) Baleiza˜o, C.; Gigante, B.; Garcia, H.; Corma, A. Tetrahedron Lett. 2003, 44, 6813-6816. (s) Karimi, B.; Ma’Mani, L. Org. Lett. 2004, 6, 4813-4815.

7.(a) Yang, Z.; Yi, Y.; Zhong, M.; De, S.; Mondal, T.; Koley, D.; Ma, X.; Zhang, D.; Roesky, H. W. Chem. Eur. J., 2016, 22, 6932. (b) Liberman-Martin, A. L.; Bergman,R. G.; Tilley, T. D. J. Am.Chem. Soc., 2015, 137, 5328. (c) Yadav, S.; Dixit, R.; Vanka, K.; Sen, S. S. Chem. Eur. J., 2018, 24, 1269. (d) Harinath, A.; Bhattacharjee, J.; Nayek, H. P.; Panda, T. K. Dalton Trans, 2018, 47, 12613 – 12622.

8. (a) Li, J.; Yu, T.; Luo, M.; Xiao, Q.; Yao, W.; Xu, L.; Ma. M. J. Organomet. Chem 2018, 874, 83-86. (b) Kurono, N.; Yamaguchi, M.; Suzuki, K.; Ohkuma, T. Chem. Commun., 2018, 54, 3042-3044.