INTRODUCTION

Organic fluorescent polymers are of great interest for a wide range of applications in optical devices, pharmaceuticals, probes, and engineering materials, owing to their fluorescent nature and fluorescence behavior.¹–¹⁶ Recently, Yujie et al. and coworkers synthesized a series of maleimide-based tunable fluorescent derivatives.¹⁷ Zhao et al. reported the fluorescence behavior of alternating copolymers and their derivatives, demonstrating that the emission of copolymers containing maleimide moieties originates from their carbonyl groups.¹⁸ Compounds of this class also exhibit strong solvent polarity–dependent variations in their photophysical properties, as observed for the donor–acceptor-type styrylpyrazine compound E,E-2,5-bis[2-(3-pyridyl)ethenyl]pyrazine (BPEP) in different solvents.¹⁹ The synthesis of OMPBA and OMPPD has been investigated to determine their ground- and excited-state dipole moments with respect to solvent polarity parameters.²⁰ Maliyealtundas and coworkers studied pyridine derivatives in benzene–ammonium acetate systems and reported antimicrobial activity of the resulting products.²¹ Similarly, Cui et al. reported boron complexes based on spiroborate–enolate–pyridine structures for solvatochromic studies, including absorption, fluorescence, and solvent polarity effects, which showed high quantum yields in their aggregated state.²²

In this work, we report the synthesis of 2-amino-4-(2,4,6-trimethoxyphenyl)-6-phenylpyridine-3-carbonitrile (MAP) through a one-pot reaction in benzene. Maleimide–pyridine homopolymers were also prepared using maleic anhydride and polymerized in the presence of AIBN at 65 °C under a nitrogen atmosphere. The trimethoxy-substituted pyridines, which contain donor–acceptor substituents, exhibited absorption and emission properties characteristic of solvatochromism. Both classes of compounds were found to be fluorescently active in the UV region, displaying intense yellow and blue fluorescence with high brightness, independent of the excitation wavelength. The incorporation of terminal maleimide groups into pyridine produced poly(pyridine–maleimide) homopolymers, which showed weak fluorescence in the UV region. The fluorescent polymer was characterized using ¹H NMR, ¹³C NMR, and TGA/DTA analyses. Its optical properties were examined by UV–Vis absorption and fluorescence spectroscopy, while its ground- and excited-state properties were further studied using density functional theory (DFT) and time-dependent density functional theory (TDDFT) methods.

Materials and Methods

Trimethoxy benzaldehyde, Malonitrile, Acetophenone, Maleic anhydride, Phasphorus pentoxide, α0, α0-azobis (isobutyronitrile) and Solvents were purchased from Merck India Ltd. The radical initiator of α0,α0-azobis (isobutyronitrile) was purified by crystallization from methanol. The proton nuclear magnetic resonance spectra were recorded on a Brucker 400 Mhz. FTIR spectral studies were carried out in Perkin-Elmer Spectrum FT-IR spectrometer. UV–Vis absorption spectrums were recorded on a Perkin Elmer LAMBDA 950 spectrophotometer and fluorescence measurements on Spectra Max Fluorolog-3 at room temperature. Fluorescence life time was characterized by JOBIN-VYON M/S. The thermal gravimetric analysis was carried out in air at 10 °C /min on a NETZSCH TG-DSC-409 and Gel Permeation Chromatography (GPC) on HIMADZU LC-20AD, at a heating rate of 10 °C/min

EXPERIMENTAL

Preparation of 2-amino-4-(2,4,6-trimethoxyphenyl)-6-phenylpyridine-3-carbonitrile (MAP)

Sheme 1 represents the preparation of trimethoxy Benzaldehyde (0.03 mol), acetophenone (0.03 mol) and malononitrile (1.98 g, 0.03 mol) in toluene (50 mL) with ammonium acetate as a catalyst (17 g, 0.23 mol). The mixture was refluxed for 8 h. The reaction was monitored by TLC. After completion of the reaction, the mixture was filtered off and the ammonium chloride was washed through water and the crude product was obtained. The residue was recrystallized from ethanol to give Pale yellow powder with 85 % yield.

m.p.: 185-194 °C; Color: Yellow; EIMS [M+2]: 269.23; IR (KBr, cm-1): 3,394 and 3,312 (NH2), 3,177 (ArH), 2,218 (CN).MA) 1H NMR(CDCl3) δ: 7.37-7.35 (S 1H J =5.6 Hz, Ar–H), 7.52 -7.51 (m, 2H, J =5.6 Hz, Ar–H), 7.73 (H, Ar-H, ) (5H, Ar),6.2,s (2H,NH2), 3.9 m (9H, J =5.6 Hz ,Ar-OCH3, ).13C NMR (CDCl3) δ:53, 55, 76, 77, 90, 104, 108,114, 115,124,128, 130, 37, 129, 130, 133, 142, 161, 164, 174.

Synthesis of Monomer and polymer (MAPH)

In a 100 ml three necked flask equipped with a mechanical stirrer and a reflux condenser, pyridine – maleimide (0.01mol, 0.98 g) dissolved in 70 mL acetone was charged. The solution was stirred at ambient temperature, and pyridine (0.01 mol, 3.5 g) was added in portions over 30 min. The reaction mixture turned into yellow solid. After stirring for 2 hrs the slurry was filtered. The solid was washed with acetone, and then dried at 60 oC under vacuum to give yellow powder product. The yellow solid taken in 100 ml flask with stirrer and a condenser, dissolved dimethyl form amide and, P2O5, catalytic amount of sulphuric acid was added. The mixture was heated an oil bath at 65 °c for 4 hrs. After the completion of the reaction, the mixture was cooled and poured into 50 ml of water. The solid was filtered, washed with water and recrystallized from ethanol then dried in the vacuum desiccator over CaCl2.

The monomer was added in THF (20 mL), AIBN and the flask tube was submerged into an oil bath at 65 °C and removed after 4 hours magnetic stirring under nitrogen. When the reaction was finished, the polymer was precipitated in ethanol into an excess of acetone while stirring, repeating the dissolving precipitation two times. The precipitates were filtered and collected, then dried in a vacuum oven at room temperature for 10 h.

IR (KBr, cm-1): 3,177 (ArH), 2,218 (CN). 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ: 8.148 -8.109 (S 1H J =15.9 Hz, Ar–H), 7.377 -7.261 (m, 7H, Ar–H), (5H, Ar), 1 – 2.8, m (CH-CH), 3.8 m (9H, J =5.6 Hz, Ar-OCH3,). 13C NMR (CDCl3) δ: 53, 55, 76, 77, 90, 104, 106, 124, 128, 130, 37, 129, 130, 133, 142, 161, 164, 174.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The starting compound 4-(2, 4, 6-trimethoxyphenyl)-2-(2, 5-dioxo-2H-pyrrol-1(5H)-yl)-6-phenylpyridine-3-carbonitrile) was synthesized according to the literature. The synthetic procedures of polymers (MAPH) are shown in scheme 1. Starting Polymer is easily prepared by radical polymerization using AIBN initiator in the presence of THF at 65 °C under atmospheric condition. The Homo-polymers were characterized using 1HNMR (proton nuclear magnetic resonance-)spectra, and the homopolymer was identified by (shimadzu Lc-20AD) gel permeation chromatography.

In IR spectra, symmetrical and unsymmetrical stretching frequency of CONH2 is in between 3,411–3,300, and 1598 cm-1. The stretching vibration of C–N in nitrile group appeared at 2,218 cm-1. The 1H NMR spectra in CDCl3 was shown Fig.1

The aromatic proton from both the MAPH and MAP was identified by 1H-NMR spectra as shown in Fig. 4. The aromatic protons of polymer from both (MAP, MAPH) form broad absorption at 8.2, 7.7 and 7.37 ppm and peaks at 1.2-2.8 ppm are assigned to the absorption of the -CH- group within maleimide ring. The absence of -NH2 group in the polymer was established through 1H-NMR spectrum.

UV–vis Absorption

Fig. 7. shows the UV absorption spectra of MAP and PMAH in same solvent. It is seen that both the MAP and polymer exhibits similar absorption spectra in the solvent. This result indicates that the absorption spectra of these compounds are caused mainly from the pyridine chromophore moiety. As shown in Fig. 7, without polymer the MAP shows absorption bands centered at 425 and 440 nm.

Fluorescence Behavior of MAP, MAPH Figure: 7 shows the Fluorescence spectra of MAP and MAPH in ethanol with identical wavelengths and shapes. Their Fluorescence peaks are considered to be emitted by the same chromophore such as pyridine-maleimide moiety. The concentration dependence of the Fluorescence intensities indicates that, at any concentration, the fluorescence intensity of MAP is always higher than that of MAPH. The color of the solution changes from yellow to green, as shown in Fig. 7(D inset) which allows the detection of maleimide with the naked eye.

Fig. 7 (A) UV spectra of fluorescent pyridine (MAPH) (B) emission spectra of fluorescent pyridine (MAPH) (C) Florescence life time Spectrum polymer (MAPH)

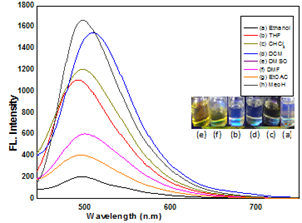

Solvatochromic study

When the spectroscopic band occurs in the UV visible part of the spectrum solvatochromism is observed as a change of color and the behavior of MAP in various protic and aprotic solvents. For this purpose, the absorption spectra of the MAP are measured in eight various solvents at a concentration 10–4 mol. Fluorescence emission spectra of MAP in ethanol shows emission maxima at 490–500 nm which demonstrates blue shift. MAP shows red shift in various solvents (CHCl3, DMF, DCM and EtOAC ). The maximum wavelength of absorption and emission for (MAP) are summarized in Table 1. In UV region chloroform, DCM, ethanol and THF, ethyl acetate emits the blue color and DMF, DMSO gives yellow color. The less number of carbonyl group in MAPH affects the extent of their interaction with the solvent, thus weakening the absorption and emission.

Fig. 8. Solvatochromism of MAP in various solvents.

Table. 1: Photophysical Properties of MAP in Different solvents

| Solvents | Appearance | λam(nm) | λem(nm) |

| DMSO | yellow | 445 | 490 |

| DMF | yellow | 440 | 500 |

| Ethylacetate | blue | 430 | 490 |

| Ethanol | blue | 430 | 495 |

| Methanol | blue | 430 | 485 |

| CHCl3 | blue | 425 | 410 |

| DCM | blue | 430 | 480 |

| THF | Blue | 440 | 480 |

Abbreviation: λab – absorption wavelength, λem – emission wave-length,

DMSO – dimethyl sulfoxide, DMF – dimethylformamide, THF-

tetrahydrofuran, DCM-dichloromethane.

Thermal Properties of polymer

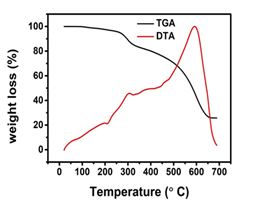

Thermal Studies

The thermal behavior of the homopolymer (MAPH) was studied. Samples (10 mg) were placed in a crucible and heated up to 800 °C at a rate of 10 °C/min in inert nitrogen with Al2O3 as a reference material. The TG–DTA of the polymer (MAPH) was studied; herein, we only show the curves of the polymer decomposition process (in Fig.9.). The polymer has very good thermal stability up to 200 °C with the endothermic peak at 200 °C. The weight loss occurs due to the liberation of CO2 molecules in the temperature range of 200 °C to 300 °C. In the next stage, the weight loss of in the temperature range of 301 °C to 600 °C was due further liberation of CO2. On further heating, the complete decomposition of polymer occurs at 700 °C.23, The presence of appreciable peak around 100°C in the DTA analysis shows the presence of water molecules in the polymer.

Fig.9. Thermal stability polymers (MAPH)

Density functional theory studies

DFT calculations were performed with B3LYP/6-3+G basis sets by using GAUSSIAN 09W of program. The frontier molecular orbitals are on important tool in the electronic and optical properties of the molecules. The HOMO-LUMO energy gaps described that the chemical reactivity and also predict the various aspects of pharmaceutical properties of drug designing of the molecules. The Homo as an electron HOMO-LUMO represent acceptor in nature and HOMO-LUMO energy gay show that the chemical reactivity of the molecules. The Frontier molecular orbital of Homo and Lumo of CPD name are shown in fig.10

According to compound 3 Homo is mainly localized over the entire molecule except trimethothy substituted benzene ring Lumo is characterized by a charge distribution on pyridine and benzene ring except methothy group benzene ring. The homo –lumo transition implies on electron density transfer to nitrile and amino group from pyridine 23. The Homo-lumo energy gaps are -8.2677 ev in gas phase for CPD title compound computed at b3lyp/6-3+G* (d,p).Which shows that lower energy gap and also presence of charge transfer with in the molecule.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the polymers namely 2-amino-4-(2,4,6-trimethoxyphenyl)-6-phenylpyridine-3-carbonitrile are synthesized successfully. The obtained results from spectroscopic are in good agreement with previous literature.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests regarding the publication of this article.

REFERENCES

- Baranello, M. P., Bauer, L., & Benoit, D. S. W. Biomacromolecules., 2014, 15(7), 2629.

- Thombare, V. J., Holden, J. A., Pal, S., Reynolds, E. C., Chattopadhyay, A., Brien-Simpson, O. N. M., & Hutton, C. A. Tetrahedron. 2018, 74(12), 1288.

- Kavallieratos, K., Rosenberg, J. M., Chen, W.-Z., & Ren, T. J. Am. Chem. Society. 2005, 127(18), 6514.

- Patra, S. K., Sheet, S. K., Sen, B., Aguan, K., Roy, D. R., &Khatua, S. J. Org. Chem., 2017, 82(19), 10234.

- .Zhang, X., Jin, Y.-H., Diao, H.-X., Du, F.-S., Li, Z.-C., & Li, F.-M. Macromolecules., 2003, 36(9), 3115.

- Otani, T., Tsuyuki, A., Iwachi, T., Someya, S., Tateno, K., Kawai, H., Shibata, T. Angewandte Chem,. 2017. 56(14), 3906.

- Bode, S., Bose, R. K., Matthes, S., Ehrhardt, M., Seifert, A., Schacher, F. H., Schubert, U. S. Poly. Chem., 2013, 4(18), 4966.

- Wang, Y.-Z., Deng, X.-X., Li, L., Li, Z.-L., Du, F.-S., & Li, Z.-C. Polym. Chem., 2013, 4(3), 444.

- Hong Y. S.; Mun H. N.; Zhen Y. S.; Paul A. M.; Jonathan. H.; and Martin J. L. Biomol. Chem., 2009, 7(17), 3400.

- Guy, J., Caron, K., Dufresne, S., Michnick, S. W., Skene, & Keillor, J. W.J. Am. Chem. Society. 2007, 129(39), 11969.

- Giernoth, R. Angewandte Chem., 2011, 50(48), 11289.

- Marini, A., Muñoz-Losa, A., Biancardi, A., &Mennucci, B. J. Phy. Chem. B, 2010, 114(51), 17128.

- Ji, Y., & Qian, Y. RSC Adv., 2014, 4(94), 52485–52490.

- Qiao, J., Qi, L., Shen, Y., Zhao, L., Qi, C., Shangguan, D., Chen, Y. J. Mater. Chem., 2012, 22(23), 11543.

- V. Dyachenko, I.V.; and Dyachenko, V.D. Russian J. Org . Chem., 2016, 52, 1, 32.

- Chinen, A. B., Guan, C. M., Ferrer, J. R., Barnaby, S. N., Merkel, T.J., Mirkin, C. A. Fluorescence Chem. Rev., 2015, 115, 10530.

- Xie, Y., Husband, J. T., Torrent, S. M., Yang, H., Liu, W., & Reilly, R. K. Chem. Com. 2018, 54(27), 3339.

- Engui, Z.; Jacky, W. Y. L.; Luming, M.; Yuning, H.; Haiqin, D.; Gongxun, B.; Xuhui, H.; Jianhua, H.; and Ben, Z. T. Macromolecules. 2015, 48, 1, 64.

- Kumari, R., Varghese, A., Akshaya, K. B., George, L., & Lobo, P. L. J. Solu. Chem., 2018, 47(7), 1269.

- Mueller, J. O., Voll, D., Schmidt, F. G., Delaittre, G., & Barner. K. C. Chem. Commun. 2014, 50(99), 15681.

- Juan, J. Q., Li, Q., Ying, S., Lingzhi, Z., Cui, Q., Dihua S., Lanqun, M., and Chena. y. Mater. Chem. 2012, 22, 11543.

- Li, K., Cui, J., Yang, Z., Huo, Y., Duan, W., Gong, S., & Liu, Z. J. Name., 2013, 00, 1.

- Muthukumar. M., Buvanesan sri. T, venketesh. G., Kamal.C., Vennila. P., Sanja, J., Arm akovic, J.M., Sheena,Y., M Yohannan, C. P. J. Molecular Liquids. 2018, 272, 481.