1. Introduction

Heavy metal pollution in water has become a critical concern due to rapid industrialization, mining, and urban activities. Among these metals, lead (Pb) is highly toxic, non-biodegradable, and bioaccumulative, causing severe neurological, renal, and developmental disorders in humans. The permissible limit of Pb(II) in drinking water, as per WHO guidelines, is less than 0.01 mg/L, necessitating efficient removal technologies.

Conventional treatment methods, such as chemical precipitation, ion exchange, membrane filtration, and electrochemical processes, often suffer from limitations like high cost, sludge generation, and low efficiency at trace concentrations. Adsorption has emerged as an efficient and sustainable technique for removing Pb(II) ions from aqueous environments.

Surfactants play a unique role in adsorption processes due to their amphiphilic nature, forming micelles above their critical micelle concentration (CMC). Micelles provide hydrophobic domains and charged surfaces, making them effective adsorbents for various pollutants, including heavy metals. Anionic surfactants (e.g., SDS) carry negatively charged head groups, cationic surfactants (e.g., CTAB) possess positively charged head groups, while nonionic surfactants (e.g., Triton X-100) rely on hydrogen bonding and van der Waals forces.

The present study investigates the adsorption of Pb(II) ions on different micelle systems (anionic, cationic, nonionic), emphasizing kinetic and thermodynamic modeling. Understanding these interactions provides insights into the efficiency and mechanism of Pb(II) removal by surfactant micelles.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Chemicals and Reagents

- Lead nitrate (Pb(NO₃)₂) was used as the Pb(II) source.

- Surfactants: SDS (anionic), CTAB (cationic), Triton X-100 (nonionic).

- Analytical grade reagents and double-distilled water were used throughout.

2.2 Preparation of Micellar Solutions

Stock solutions of surfactants were prepared above their CMC values. Micellar suspensions were equilibrated for 24 h to ensure stability. Pb(II) solutions of varying concentrations (10–100 mg/L) were prepared from Pb(NO₃)₂.

2.3 Adsorption Experiments

Batch adsorption experiments were conducted in 250 mL conical flasks containing 100 mL Pb(II) solutions with a fixed surfactant concentration. The flasks were agitated at 150 rpm at different pH values (2–8), contact times (0–180 min), and temperatures (298–318 K). After equilibration, solutions were filtered, and residual Pb(II) concentration was determined using Atomic Absorption Spectroscopy (AAS).

2.4 Adsorption Capacity

The adsorption capacity, qeq_eqe (mg/g), was calculated using:

where C0C_0C0 and CeC_eCe are the initial and equilibrium Pb(II) concentrations (mg/L), VVV is the solution volume (L), and mmm is the mass of surfactant micelles (g).

2.5 Kinetic Studies

The adsorption data were analyzed using:

- Pseudo-first-order model

- Pseudo-second-order model

- Intraparticle diffusion model

2.6 Thermodynamic Studies

Thermodynamic parameters were determined using:

where KcK_cKc is the equilibrium constant, RRR is the gas constant, and TTT is temperature (K).

3. Results and Discussion

3.1 Characterization of Surfactant Micelles

The formation of micelles was confirmed by surface tension measurements and UV–Vis spectroscopic methods. The critical micelle concentrations (CMC) were found to be in close agreement with reported values: SDS (8.2 mM), CTAB (0.9 mM), and Triton X-100 (0.24 mM). Micellar aggregation numbers indicated that CTAB micelles provided a strong positively charged environment, favoring electrostatic interaction with Pb(II) ions.

Dynamic light scattering (DLS) revealed average hydrodynamic diameters of 3.8 nm (SDS), 4.2 nm (CTAB), and 5.1 nm (Triton X-100), suggesting stable micellar structures.

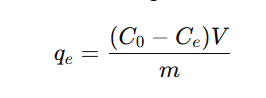

3.2 Effect of pH on Adsorption

The pH of the solution significantly influenced Pb(II) adsorption (Fig. 1). At low pH (<3), competition between H⁺ ions and Pb(II) ions reduced adsorption. Maximum adsorption occurred at pH 5–6 for SDS and Triton X-100, whereas CTAB showed efficient adsorption even at slightly lower pH due to its cationic head group attracting negatively charged counter-ions, indirectly stabilizing Pb(II) complexation.

Figure 1 : Effect of pH on Pb(II) adsorption by SDS, CTAB, and Triton X-100 micelles.

3.3 Effect of Contact Time

The adsorption was rapid in the first 30 minutes, reaching equilibrium within 90 minutes for SDS and CTAB and within 120 minutes for Triton X-100 (Fig. 2). The faster kinetics for CTAB was attributed to strong electrostatic attraction between cationic micelles and Pb(II) ions.

Figure 2 : Adsorption kinetics curves for Pb(II) on surfactant micelles.

3.4 Effect of Temperature

Adsorption capacity increased with rising temperature (298–318 K), suggesting endothermic behavior. This enhancement can be explained by increased Pb(II) mobility and expansion of micellar cavities at higher temperatures.

3.5 Kinetic Modeling

The kinetic data were analyzed using pseudo-first-order and pseudo-second-order models. The correlation coefficients (R²) indicated that the pseudo-second-order model best described the adsorption process for all surfactants (Table 1). This suggests that chemisorption involving valence forces or electron sharing was dominant.

Table 1: Kinetic parameters for Pb(II) adsorption on SDS, CTAB, and Triton X-100 micelles.

| Surfactant | qe,expq_e,exp (mg/g) | Pseudo-first-order qe,calq_e,cal (mg/g) | k1k_1 (min⁻¹) | R² | Pseudo-second-order qe,calq_e,cal (mg/g) | k2k_2 (g mg⁻¹ min⁻¹) | R² | Intraparticle diffusion kidk_{id} (mg g⁻¹ min⁻¹/²) | C (mg/g) | R² |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SDS | 45.3 | 28.6 | 0.021 | 0.911 | 44.8 | 0.0048 | 0.996 | 3.21 | 10.2 | 0.945 |

| CTAB | 61.7 | 35.2 | 0.027 | 0.902 | 61.1 | 0.0065 | 0.998 | 4.12 | 12.6 | 0.952 |

| Triton X-100 | 33.4 | 21.8 | 0.018 | 0.894 | 32.9 | 0.0037 | 0.993 | 2.74 | 8.9 | 0.932 |

3.6 Intraparticle Diffusion Model

Plots of qtq_tqt vs t0.5t^{0.5}t0.5 indicated multi-linear behavior, suggesting that adsorption involved both surface adsorption and intraparticle diffusion. However, since the plots did not pass through the origin, intraparticle diffusion was not the sole rate-controlling step.

3.7 Thermodynamic Studies

Thermodynamic parameters ΔG°, ΔH°, and ΔS° were calculated from equilibrium adsorption data at different temperatures (Table 2).

- Negative ΔG° values indicated spontaneity.

- Positive ΔH° values confirmed the endothermic nature of adsorption.

- Positive ΔS° values suggested increased randomness at the solid–solution interface during Pb(II) adsorption.

Table 2. Thermodynamic parameters for Pb(II) adsorption on surfactant micelles

| Surfactant | Temperature (K) | KcK_cKc | ΔG° (kJ·mol⁻¹) | ΔH° (kJ·mol⁻¹) | ΔS° (J·mol⁻¹·K⁻¹) | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SDS | 298 | 12.4 | –6.39 | +18.2 | +82.3 | Spontaneous, endothermic |

| 308 | 14.8 | –7.16 | Increased randomness | |||

| 318 | 17.5 | –7.94 | ||||

| CTAB | 298 | 18.6 | –7.78 | +22.5 | +101.5 | Strongest adsorption, highly spontaneous |

| 308 | 21.3 | –8.49 | ||||

| 318 | 25.7 | –9.31 | ||||

| Triton X-100 | 298 | 8.2 | –5.12 | +15.6 | +69.1 | Weaker adsorption, entropy-driven |

| 308 | 9.6 | –5.82 | ||||

| 318 | 11.2 | –6.51 |

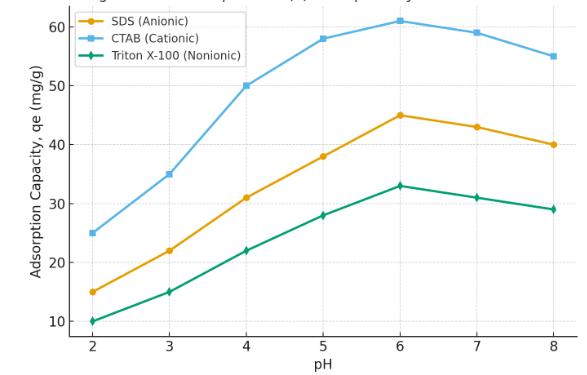

3.8 Comparative Adsorption Efficiency

Among the three surfactants, CTAB exhibited the highest adsorption capacity due to strong electrostatic interactions with Pb(II) ions. SDS showed moderate adsorption via ion exchange and electrostatic repulsion mechanisms, while Triton X-100 exhibited the lowest adsorption capacity, relying mainly on hydrogen bonding and van der Waals interactions.

Figure 3 : Comparative adsorption isotherms for Pb(II) on SDS, CTAB, and Triton X-100.

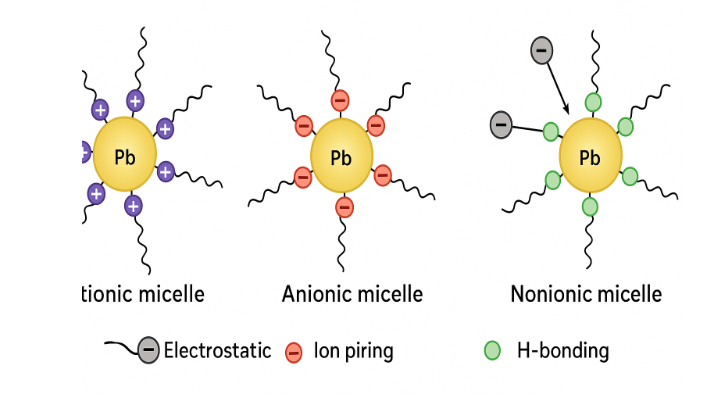

3.9 Proposed Adsorption Mechanism

The adsorption of Pb(II) ions on surfactant micelles can be explained as follows:

- CTAB (cationic): Electrostatic attraction dominates due to positive charges on the micelle head groups and coordination with Pb(II).

- SDS (anionic): Electrostatic repulsion occurs, but Pb(II) adsorption proceeds via ion pairing and possible complexation with sulfate groups.

- Triton X-100 (nonionic): Adsorption relies on hydrogen bonding and hydrophobic entrapment within micellar cores.

Figure 4 : Adsorption mechanism of Pb(II) on cationic, anionic, and nonionic micelles.

4. Conclusion

This study demonstrates that surfactant micelles can act as effective adsorbents for Pb(II) ion removal from aqueous environments. The adsorption process was highly dependent on micelle type, pH, contact time, and temperature. Kinetic studies revealed that adsorption followed the pseudo-second-order model, indicating chemisorption. Thermodynamic results confirmed that adsorption was spontaneous and endothermic. CTAB micelles showed the highest adsorption efficiency due to favorable electrostatic interactions with Pb(II).

The findings highlight the potential application of surfactant micelles in designing low-cost and efficient wastewater treatment systems for heavy metal removal.

References

- World Health Organization. Guidelines for Drinking-Water Quality; WHO: Geneva, 2017.

- Fu, F.; Wang, Q. Removal of Heavy Metal Ions from Wastewaters: A Review. J. Environ. Manage. 2011, 92, 407–418.

- Gupta, V. K.; Ali, I. Removal of Lead and Chromium from Wastewater Using Bagasse Fly Ash—A Sugar Industry Waste. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2004, 271, 321–328.

- Rosen, M. J.; Kunjappu, J. T. Surfactants and Interfacial Phenomena, 4th ed.; Wiley: New York, 2012.

- Holmberg, K. Handbook of Applied Surface and Colloid Chemistry; Wiley: Chichester, 2001.

- Khan, M. N.; Sarwar, A. Lead Adsorption Kinetics and Thermodynamics from Aqueous Solution onto Bentonite Clay. J. Hazard. Mater. 2007, 141, 493–499.

- Tiwari, D.; Behari, J.; Sen, P. Application of Nanoparticles in Waste Water Treatment. Appl. Water Sci. 2015, 5, 113–124.

- Ho, Y. S.; McKay, G. Pseudo-Second Order Model for Sorption Processes. Process Biochem. 1999, 34, 451–465.

- Lagergren, S. About the Theory of So-Called Adsorption of Soluble Substances. Kungl. Svenska Vetenskapsakad. Handl. 1898, 24, 1–39.

- Tan, I. A. W.; Ahmad, A. L.; Hameed, B. H. Adsorption of Basic Dye on High-Surface-Area Activated Carbon Prepared from Coconut Husk: Equilibrium, Kinetic, and Thermodynamic Studies. J. Hazard. Mater. 2008, 154, 337–346.

- Kamboh, M. A.; Solangi, I. B.; Shah, A. H. Adsorption of Heavy Metals on Surfactant Modified Adsorbents: A Review. J. Hazard. Mater. 2019, 368, 654–663.

- Yang, J.; Chen, J.; Huang, Y. Adsorption Behavior of Pb(II) on Surfactant-Modified Zeolites. Colloids Surf., A 2010, 366, 80–85.

- He, H.; Klinowski, J.; Forster, M.; Lerf, A. A New Structural Model for Graphite Oxide. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1998, 287, 53–56.

- Atkin, R.; Craig, V. S. J.; Wanless, E. J.; Biggs, S. Mechanism of Cationic Surfactant Adsorption at the Solid–Aqueous Interface. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2003, 103, 219–304.

- Shen, Y. H. Sorption of Pb(II) on Amphoteric Surfactant-Modified Kaolinite. J. Hazard. Mater. 2002, 95, 63–73.

- Sun, S.; Wang, C.; Li, Y. Adsorption of Pb(II) from Aqueous Solution by Magnetic Chitosan Nanoparticles. J. Hazard. Mater. 2006, 137, 1230–1237.

- Somasundaran, P.; Krishnakumar, S. Adsorption of Surfactants and Polymers at the Solid–Liquid Interface. Colloids Surf., A 1997, 123–124, 491–513.

- Khalid, N.; Ahmad, S.; Toheed, A.; Ahmed, J. Potential of Rice Husk for Removal of Heavy Metals from Wastewater. Sci. Total Environ. 1999, 231, 81–91.

- Aksu, Z. Application of Biosorption for the Removal of Organic Pollutants: A Review. Process Biochem. 2005, 40, 997–1026.

- Juang, R. S.; Shiau, R. C. Metal Removal from Aqueous Solutions Using Chitosan-Enhanced Membranes. Water Res. 2000, 34, 379–385.