Introduction: Lipases and phospholipases are enzymes that catalyze the hydrolysis of triglycerides and phospholipids, respectively. These enzymes are gaining increasing importance due to their broad applications in biotechnology. Their significance is further amplified by advancements in industrial technology and sophisticated controlled manufacturing processes, making them highly valuable in industries such as food, detergents, cosmetics, pharmaceuticals, leather, lubricants, and polyester production. Lipases are particularly useful for producing biomodified fats and as biocatalysts for converting oils into alternative energy sources. Their ability to exhibit high chemo- and enantioselectivity makes them ideal for industrial reactions like esterification, interesterification, transesterification, acidolysis, and alcoholysis. Phospholipases, on the other hand, are primarily used in the health industry, along with food manufacturing.

Due to their extensive industrial applications, there is growing interest in the research and development of new sources for these enzymes, focusing on optimizing their activity, reducing costs, and ensuring their easy availability. The main natural sources of lipases and phospholipases are plants, animals, and microorganisms, but plant-derived enzymes, especially those from seeds, offer distinct advantages over animal and microbial enzymes. These advantages include higher specificity, lower cost, widespread availability, and ease of purification.

Considerable research has been conducted on the physicochemical properties of seeds from the Prunus genus, particularly regarding their oil and fatty acid profiles at various ripening stages. The current study focuses on the enzymatic activity (lipases and phospholipases) of Prunus species, specifically from ultrasonically defatted seeds of different cultivars such as Prunus domestica, Prunus avium, and Prunus persica. Enzyme extraction, activity assays, and optimization were carried out under various conditions of temperature, pH, and solvent types. The seeds of these species are often considered agro-industrial waste after their fruits are processed into products like jams, juices, and marmalades and stored in dry form.

The findings of this study could significantly contribute to the production of valuable enzymes like lipases and phospholipases, which could be used in specialized industrial processes such as detergent production, pharmaceuticals, lipid synthesis, and flavoring compound manufacturing. Additionally, these results could help address the issue of agro-waste management in food processing industries by promoting the utilization of seed by-products.

EXPERIMENTAL

Chemicals and reagents

Chloroform, methanol, citric acid, sodium citrate, sodium diethyldithiocarbamate, lecithin, acacia, hexane, stearic acid, olive oil, diisopropyl ether, n-heptane and cyclohexane. All chemicals and solvents used in this study were of analytical reagent grade were acquired from Central Chemicals, Lahore originate to Merck (Darmstadt, Germany) and Panreac (Barcelona, Spain) while GenPure water system (Thermo Scientific, USA) was used to obtain ultrapure water (18 MΩ.cm).

Collection of prunus species seeds

The fruit of prunus species namely prunus domestica, prunus avium and prunus persica were collected from the Gilgit-Baltistan (35° 21′ 0″ N, 75° 54′ 0″ E) Northern Province of Pakistan, samples were collected from three sites (Figure 1) and a voucher specimen (PS-010517) was deposited at the Institute’s herbarium. Decortication were done with 20 % Sodium chloride 8 and collected seed kernel were kept in dry forced oven (Memmert, Germany) at 50 ◦C for six hrs.

Defatification of seeds

The seeds of prunus species were ground into fine powder. Ultrasonic assisted extraction employed for complete defatification of seeds. Hielscher ultrasonic UP 400 S used for sonication. Lipids were extracted by opting conditions after optimization of different parameters like solvent and seed ratio (ml:mg), sonic power and solvents used. The conditions used for seed defatification for the present study was 300 W sonic power, 10:10 (solvent/seed) ratio whereas mixture of chloroform and methanol (2:1 v/v) were used as the solvent. Extraction time was 30 min. and the temperature was 50 ◦C 9.

Extraction of lipids

The seeds of prunus species were ground into fine powder. Ultrasonic assisted extraction employed for defatification of seeds. Ultrasonic UP 400S (Hielscher-Ultrasound Technology, Germany) used for sonication. Lipids were extracted by opting conditions after optimization of different parameters like solvent (mL) and seed (mg) ratio, sonic power and solvents used. The conditions used for seed defatification as followed; 300 W sonic power, 10 mL/gm solvent/seed ratio and mixture of chloroform and methanol were used as the solvent in 2:1, v/v. Extraction time was 30 min and the temperature was kept at 50 ◦C 9.

Extraction of enzymes

20 g defatted seeds of each prunus species were suspended separately in 0.1 M citrate buffer at pH = 6.5 (pH meter, Orion 5 Star, Thermo Scientific, UK) and were shaked in orbital shaker (Thermo Scientific™ MaxQ™, USA) for 1.0 hr at 45 ◦C. The extracts centrifuged (Thermo Scientific™, USA) for 15 min at 4000 rpm. The supernatant were diluted further with 1:1 v/v ratio of distilled water and 0.1 M citrate buffer. The extracts containing lipases and phospholipases were stored in refrigerator for enzymes assays.

Enzymes assays

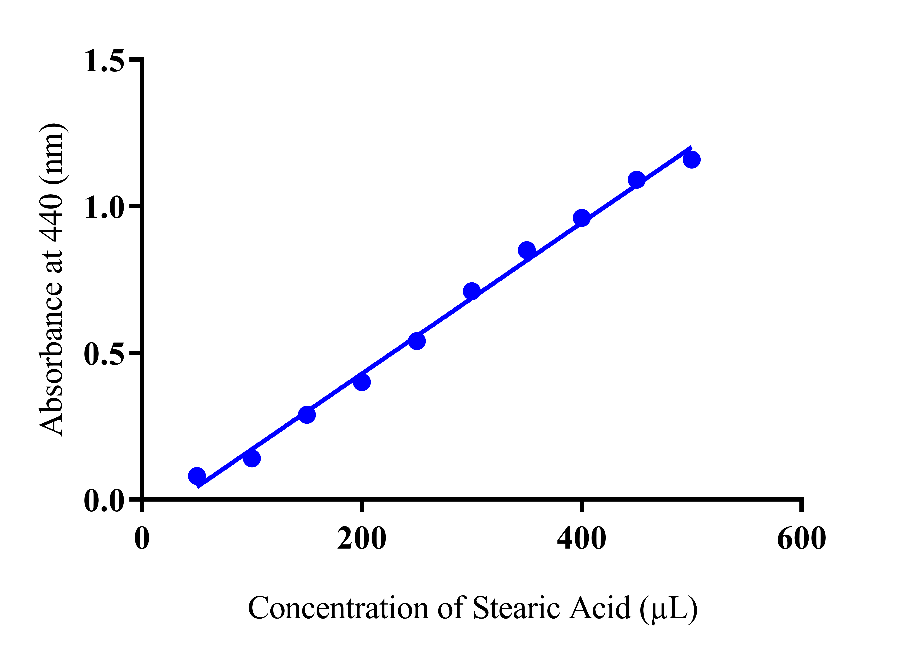

The spectrophotometric method was used for the determination of lipase and phospholipase activity. olive oil (10 % in water) and acacia gel emulsion was used as the substrate for lipase enzyme while 10 % emulsion of lecithin in water used as the substrate for phospholipase enzymes. Assay mixture containing 5 mL substrates emulsions, 5 mL chloroform, hexane (1:1, v/v) mixture, 2.5 mL Cu –TEA reagent which were centrifuged for 30 min at 7000 rpm. Absorbance of supernatants were measured at 440 nm after adding 0.5 mL of sodium diethyldithiocarbamate (0.1 % in H2O). Different concentration of stearic acid used as the standard for making standard curve graph for enzyme activities.

Lipolytic characterization

Effect of pH and temperature

Optimum pH for the lipolytic activities of lipases and phospholipases were determined by using phosphate buffer covering the range of pH 3-9. For optimum temperature absorbance were measured after every 5 ◦C rise of temperature from 30 to 70 ◦C 1.

Effect of solvents

Diisopropyl ether, n-heptane and cyclohexane used to determine the enzymes activities in place of chloroform, hexane mixture (1:1, v/v) as solvent while considering the rest procedure as it is .The temperature and pH kept constant at which enzymes exhibited their maximum activities.

Statistical analysis

All the experiments were conducted in triplicate. Signal to noise ratio was used to determine the maximum extraction of enzymes from the prunus species by considering larger the better (LTB) formula for each experiment.

Larger the better – SNRj= -10 log

Whereas analysis of variance (ANOVA) used to determine the percentage parameter contribution towards the optimal extraction of enzymes with the help of below mentioned formula.

% age contribution of a factor = SSf /SST x100

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Extraction of oils

Plants seeds are not only the main source of oils, protein, carbohydrates, and minerals but also produce enzymes utilized by the developing embryo during the storage time in the form of fatty acid 10. Enzymes activity indicated by the hydrolysis of glycerides and experimentally evidenced by the liberation of the free fatty acids .The concentration of these free fatty acids attributed the lipolytic activities of lipase and phospholipase in the seeds bearing polar and neutral lipids. The amount of extracted oil by ultrasonic assisted extraction (UAE) from seeds of prunus species were p. domestica (44.70 %), p. Avium (42.75 %) and p. persica (41.9 %). The reason for UAE selection was due to its highly efficiency for seeds oil extraction and secondly technique was ideal for isolation the seeds compounds present in minute quantities and sensitive to heat 11. The present study focused on the seeds which itself contain rich amount of oil and free fatty acid so, defatification was done prior the enzymatic assay. Ultrasonically treated seeds ensured the complete removal of lipid and free fatty acids in the seeds.

Extraction of enzymes

Incubation time, temperature, pH, nature of buffer, agitation speed (rpm) were found the influential parameters of enzymes assays. As the amount, conditions and index of pH varies from seeds to seeds so optimization of the process was essential to achieve the target of the present research work. Nine designed experiments were ran with incubation time, concentration of the substrate and agitation speed (variable parameters) along with their levels (low to high values). The concentration of free fatty acids showed the action of the enzymes performance as these enzymes have been recognized as the hydrolysis promoters 12. Concentration of liberated fatty acid (µL) as a result of hydrolysis of fats of each experiment (n = 3). The selection of Taguchi method for the present study was on the basis of this model version for investigating the production problems and the loss function. Loss of function calculated the differences between experimental and predicted values and this was only possible to calculate signal to noise ratio (SNR) .The SNR values were the probable outcome served as the objective of this optimization study. The variable parameters, concentration of liberated fatty acids, their mean values. SNR and SNRT are mentioned in Table 1 by successfully adopting L9 orthogonal array with 9 runs (Tauguchi model).

Table 1. L9 orthogonal array design (Taguchi method) for Concentration of free fatty acids (µL) and SNRs due to variable parameters.

| Experiment | Concentration of substrate (A) | Incubation temperature (B) | Agitation speed (C) | Mean values of fatty acids (µL) (n = 3) | SNR | SNRT | |

| 1 | 10 | 30 | 2000 | 110 | 40.87 | 44.3 | |

| 2 | 10 | 45 | 3000 | 200 | 46.0 | ||

| 3 | 10 | 60 | 4000 | 270 | 48.62 | ||

| 4 | 20 | 30 | 2000 | 180 | 45.08 | ||

| 5 | 20 | 45 | 3000 | 202 | 46.09 | ||

| 6 | 20 | 60 | 4000 | 234 | 47.4 | ||

| 7 | 30 | 30 | 2000 | 108 | 40.66 | ||

| 8 | 30 | 60 | 3000 | 120 | 41.60 | ||

| 9 | 30 | 60 | 4000 | 132 | 42.36 |

To achieve optimal combination of variable parameter with effective level, signal to noise level based values (SNRL) calculated. SNRL values of each experimental variable for each of its specified level are shown in Table 2.

Table 2. Level mean SNRs of variable parameters for specific level

| Parameter ID | Parameter Description | Levels | ||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | ||

| A | Concentration of substrate | 45.16 | 46.19 | 41.54 |

| B | Incubation time | 42.20 | 44.56 | 46.13 |

| C | Agitation speed | 42.17 | 44.56 | 46.13 |

The SNRL values of each independent variable (A, B, C) at their levels (1, 2, 3) showed the direct influence on concentration of fatty acids (CoFA).Big value of SNRL greater the influence of that particular variable of that level to perform the hydrolysis activity of enzymes on the substrate. .Analysis of variance (ANOVA) applied to determine the significant contribution towards the maximum CoFA at optimal levels represented in Table 3.The values obtained after taking sum of square of fifth factor (SSf) and total sum of square (SST) as calculated by earlier researchers 13.

Table 3. Parameters contribution towards optimal CoFA

| Variable Parameters | Significant contribution in terms of percentage |

| Concentration of substrate | 43.19 |

| Incubation time | 28.16 |

| Agitation speed | 28.65 |

Concentration of the substrate found the more significant parameter in the present study as compared to incubation time and agitation speed. The optimal concentration of the substrates were found in most of the enzymatic studies.

Lipolytic activity Evaluation

The lipolytic activity are the attributor of lipases and phospholipases enzymes so evaluation of the activity was made by monitoring the enzymes activities and stabilities at various temperature, pH and solvents. Prior to take the absorbance of liberated fatty acids of prunus species a standard curve plot drown of different concentrations of stearic acid (Fig. 1) .The selection of stearic acid made due to stability and easily availability according to local climate and environment. Previous work reported the successfully use of stearic acid while other fatty acid (oleic acid) also found as the control reagent for enzymatic studies 14.

Fig. 1 Absorbance of different concentrations of stearic acid

Activity of lipases and phospholipases at different pH

Characterization of enzymes based upon the external factors like pH and temperature furthermore, their activity correlate with these parameters to make these enzymes viable for different industries, to control the rancidity and increase the shelf life of the product 15. Variation in pH play the vital role in the efficiency of lipolytic activity of enzymes. To optimize the pH for lipases and phospholipases to make the enzymes viable for different industries experiment were carried out with the variation of pH covering the range of acidic to alkaline 3-9. Both the enzymes (lipase and Phospholipase) hydrolyzed the substrate triglycerides of neutral and polar lipids measured in the form of absorbance. The absorbance of liberated fatty acid from three prunus species are profiled in Fig 2.

Fig. 2 Effect of pH on the absorbance of liberated fatty acids due to lipases and phospholipases from three prunus species

Both enzymes showed single peak point of absorbance when measured absorbance at different pH which clearly indicated the presence of single nature enzyme ,the present finding was in accordance with the previous study of lipolytic activities of extracted lipases of peanut, walnut, castor and rape seeds which showed single optimal point of pH 15.The concentration of free fatty acids as a result of breakdown of triglyceride structure of substrates were reported in Table 4 due to calculated activities of lipases and phospholipases enzymes present in the experimentally defatted Prunus species seeds in terms of µU.

Table 4. Activity of enzymes (lipases and phospholipases) of prunus species and concentration of free fatty acid (activity indicator) at different pH

| Enzymes | pH | Prunus species | |||||

| Prunus Domestica | Prunus Avium | Prunus Persica | |||||

| aConcentration of liberated of fatty acid (µL) | bActivity of enzyme (µU) | Concentration of liberated fatty acid (µL) | Activity of enzyme (µU) | Concentration of Liberated fatty acid (µL) | Activity of enzyme (µU) | ||

| Lipase Phospholipase | 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 | 35 75 120 270 120 90 30 25 65 105 250 100 80 25 | 0.28 0.6 0.96 2.16 0.96 0.72 0.24 0.20 0.52 0.84 2.00 0.80 0.64 0.20 | 35 100 135 190 100 60 20 30 45 65 100 50 35 20 | 0.28 0.80 1.08 1.52 0.80 0.48 0.16 0.24 0.36 0.52 0.80 0.40 0.28 0.16 | 50 90 130 275 440 250 90 100 120 195 255 320 235 75 | 0.40 0.72 1.04 2.20 3.52 2.00 0.72 0.80 0.96 1.56 2.04 2.56 1.88 0.60 |

a Derived from standard curve graph

b Calculated by using Guven’s equation

Activity of lipases and phospholipases at different temperature

Variation in the temperature not only influenced the changes the lipolytic activities of lipases and phospholipases but can also leading to the denaturing of the enzymes as well. Grosh and coworkers reported the complete loss of enzymatic activities at elevated temperature 16. The absorbance of fatty acid corresponded to different temperature in present study profiled in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3 Effect of temperature on the absorbance of liberated fatty acids due to lipases and phospholipases from three prunus species

The result of present work showed the optimal activity of extracted lipase and phospholipase of Prunus Avium and Prunus Domestica were observed at 40 ◦C when assayed at pH 6, likewise the stability of lipolytic activities regarding pH were around 4-7 among these species. Whereas at 35-55 ◦C both the enzymes show thermal stability which were in accordance to the previous work 14, 17 on different vegetable oil bearing seeds. The concentration of free fatty acids and activity of both enzymes (lipase and phospholipase) extracted from p. avium and p. domestica showed different values indicated the amount of enzymes present in these seeds. The lipolytic activities of Prunus Persica lipase and phospholipase showed high dependence at pH 5-7. The optimum pH of both enzymes were found to be pH 7. Stability towards temperature were well in between the range of 35-60 ◦C and at 45 ◦C the activities seemed to be maximum which is similar in another oil bearing seed of jatropha 10. Regardless the optimal point difference from the other Prunus species(p. avium and p. domestica ) the enzymes overall showed the optimal activities in neutral range and at temperature of 40 -450 C .The difference in the optimal points might be due to purity enzymes maturation stage of seeds, ripening time and climatic factors etc.

Table 5. Activities of lipases and phospholipases extracted from the Prunus species with the accumulation of liberated free fatty acids at different temperature

| Enzymes | Temp. ◦ C | Prunus species | |||||

| Prunus Domestica | Prunus Avium | Prunus Persica | |||||

| aConcentration Liberated of fatty acid (µL) | bActivity of enzyme (µU) | Concentration of liberated fatty acid (µL) | Activity of enzyme (µU) | Concentration of Liberated fatty acid (µL) | Activity of enzyme (µU) | ||

| Lipase Phospholipase | 30 35 40 45 50 55 60 65 70 30 35 40 45 50 55 60 65 70 | 58 160 280 270 160 100 80 60 35 55 150 270 250 230 150 70 55 35 | 0.46 1.28 2.24 2.16 1.28 0.8 0.64 0.48 0.28 0.44 1.2 2.16 2.0 1.84 1.20 0.56 0.44 0.28 | 60 140 190 150 120 100 70 50 30 50 90 100 90 60 50 45 40 25 | 0.48 1.12 1.52 1.20 0.96 0.80 0.56 0.40 0.24 0.40 0.72 0.80 0.72 0.48 0.40 0.36 0.32 0.20 | 45 125 440 455 320 185 125 60 35 40 100 320 385 295 210 135 85 55 | 0.36 1.0 3.52 3.64 2.56 1.48 1.0 0.48 0.28 0.32 0.80 2.56 3.08 2.36 1.68 1.08 0.68 0.44 |

a Derived from standard curve graph

b Calculated by using Guven’s equation

The stability of enzymes is very much dependent on the solvents because the solvents can alter the pH memory, thermal stability and even substrate selectivity of the enzymes .Gupta and coworkers reported inhibition of enzymes activity in different concentration of organic solvents 18. Di-isopropyl ether, n heptane and cyclohexane were used to study the stability of the prunus species extracted enzymes on already observed optimal points of temperature and pH .All the solvents showed stability against these optimal points with variation of their activities in term of concentration of fatty acid liberation and their absorbance .The figures 3-6 depicted the stability trend of extracted lipases and phospholipases due to the combination of hydrophilic solvent together with non-aqueous solvent which is in accordance to the Tsuzuki and Kitamura studies 19.

CONCLUSION

In this study, the solvent stable lipases and phospholipases from Prunus species were successfully studied regarding optimal activity at different temperature and pH, along with the specificity and concentration of the substrates. Taguchi method made possible to extract the enzymes after optimizing the parameters like substrate concentration, incubation time and agitation speed. The single neutral nature enzymes with single optimal pH and temperature could be generate the possibility of the usefulness of these enzymes in food industries as well as enable the conversion of the Prunus species seeds into commercially and economically value added products.

REFERENCES

1. Gadge, P.; Madhikar, S.; Yewle, J.; Jadhav, U.; Chougale, A.; Zambare, V.; Padul, M. Am. J. Biochem. Biotech., 2011, 7, 141-145.

2. Cancino, M.; Bauchart, P.; Sandoval, G.; Nicaud, J.-M.; André, I.; Dossat, V.; Marty, A. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry, 2008, 19, 1608-1612.

3. Neklyudov, A.; Berdutina, A.; Ivankin, A.; Karpo, B. App. Biochem. Microbiol., 2002, 38, 328-334.

4. Zhong, Q.; Glatz, C. E. J. Agric. Food Chem., 2006, 54, 3181-3185.

5. Darvishi, F.; Nahvi, I.; Zarkesh-Esfahani, H.; Momenbeik, F. BioMed Res. Int., 2009, 2009.

6. Jimenez, M.; Cabanes, J.; Gandıa-Herrero, F.; Escribano, J.; Garcıa-Carmona, F.; Perez-Gilabert, M. Anal. Biochem., 2003, 319, 131-137.

7. Barros, M.; Fleuri, L.; Macedo, G. Braz. J. Chem. Eng., 2010, 27, 15-29.

8. Gupta, A.; Sharma, P.; Tilakratne, B.; Verma, A. K. Indian Journal of Natural Products and Resources, 2012, 3, 366-370.

9. Tian, Y.; Xu, Z.; Zheng, B.; Lo, Y. M. Ultrason. Sonochem., 2013, 20, 202-208.

10. Abigor, R. D.; Uadia, P. O.; Foglia, T. A.; Haas, M. J.; Scott, K.; Savary, B. J. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc., 2002, 79, 1123-1126.

11. Jerman Klen, T.; Mozetič Vodopivec, B. J. Agric. Food Chem., 2011, 59, 12725-12731.

12. Nelofer, R.; Ramanan, R. N.; Rahman, R. N. Z. R. A.; Basri, M.; Ariff, A. B. Ann. Microbiol., 2011, 61, 535-544.

13. Kumar, R. S.; Sureshkumar, K.; Velraj, R. Fuel, 2015, 140, 90-96.

14. Eze, S.; Chilaka, F. World App. Sci, J., 2010, 10, 1225-1231.

15. Seyhan, F.; Tijskens, L.; Evranuz, O. J. Food Eng., 2002, 52, 387-395.

16. Laskawy, G.; Senser, F.; Grosch, W. CCB, Review for Chocolate, Confectionery and Bakery, 1983.

17. Altaf, A.; Ankers, T.; Kaderbhai, N.; Mercer, E.; Kaderbhai, M. J. Plant Biochem. Biotechnol., 1997, 6, 13-18.

18. Gupta, M. N.; Batra, R.; Tyagi, R.; Sharma, A. Biotechnol. Prog., 1997, 13, 284-288.

19. Tsuzuki, W.; Ue, A.; Kitamura, Y. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem., 2001, 65, 2078-2082.