- Introduction

Research indicates that by 2050 there will be a big escalation in plastic waste generation, it has been estimated to be around twelve million tons as a consequence that plastics do not biodegrade like majority of items in the world[1]. Recently microplastics have emerged as a source of immense concern, as reported by the United Nations Environmental programme, approximately three million tonnes of microplastics and over five point three million tonnes (5,300,000 tonnes) of microplastics enter the environment annually [2]. Their introduction into the environment poses a significant threat due to their persistent presence and potential long-term impact. Moreover, upon exposure to radiation, microplastics easily break down from larger plastic materials; however, their enduring existence in the food chain and ecosystems has come as a serious concern [3]. In Nigeria, minimal radiation exposure research has been conducted on the subject of microplastics in Lagos State, with a population exceeding twenty-two million and covering approximately 500 sq. km, which stands as Nigeria’s most densely populated state and the major source of plastic pollution in the country. Lagos state contributes 870,000 tonnes of plastic waste annually, and the state government has several initiatives that are aimed at addressing plastic pollution. However, this environmental threat persists despite these initiatives [4].

This study focuses on a serious objective which is identifying an overlooked source, the recycling industry, established to mitigate and alleviate the consequences of plastic overconsumption, as surfaced as an unexpected contributor to microplastic pollution[5]. Although discussions seldom delve into the impact of mechanical recycling facilities as potential sources of microplastic pollution, the entire process from plastic crushing to washing and pelletizing presents opportunities for microplastics to infiltrate the environment.

Plastic recycling is often viewed as an essential strategy to mitigate the environmental impact of plastic waste. However, recent research has indicated that plastic recycling processes might inadvertently exacerbate the microplastic pollution problem. Plastic recycling companies engage in various mechanical and chemical processes to transform plastic waste into reusable materials. These processes, if not managed rigorously, can generate microplastics through the mechanical abrasion, fragmentation, and shredding of plastic particles. Therefore, while plastic recycling companies aim to contribute positively to waste management, there is a pressing need to assess their potential role in microplastic pollution.

This research aims to figure out whether mechanical recycling facilities serve as one of the origins of microplastic pollution by identifying the presence of microplastics in effluents discharged from three mechanical recycling facilities situated in the Alimosho local government area of Lagos State. These facilities specialise in recycling Polyethylene Terephthalate (PET) (water bottles and plastic trays), High-Density Polyethylene (HDPE) (oil kegs, shampoo bottles), and Low-Density Polyethylene (LDPE) (packaging bags).

This assessment seeks to firstly ascertain the presence of microplastics found in the wastewater of selected recycling facilities (RF), identify the sources and pathways of microplastic release into the environment, identify the key factors that influence the release of microplastics by recycling facilities (RF), and finally to assess the perception on environmental and health impacts of microplastics in Alimosho local government. The findings will facilitate a discussion on the implications of recycling facilities functioning as potential point sources of microplastic pollution.

2. Materials and Methods

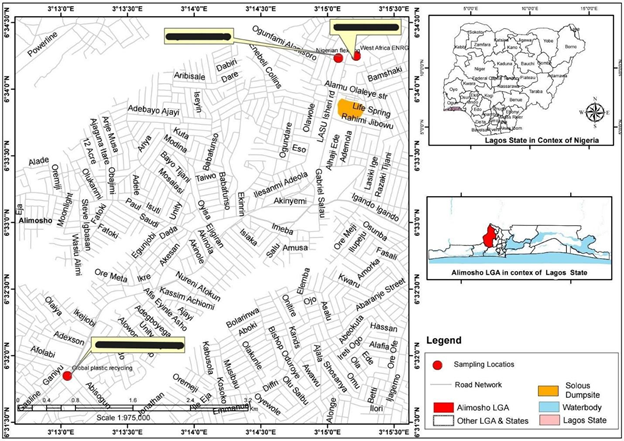

Study Area: The study area is located in the north-western part of Lagos State. Notably, Alimosho Local Government Area, positioned at coordinates 6⁰36’38’N/3⁰17’45’E, holds the distinction of being the largest local government in Lagos State, covering a land area of 185 km². The study area LASU Isheri expressway, as illustrated in Figure 1, is bounded in the North and West by River Owo and Ifako-Ijaiye, Agege respectively, and the East by Ikeja Local Government Area while it is bounded in the South by Oshodi/Isolo, Amuwo-Odofin and Ojo local Government Areas of Lagos State[6]. Alimosho is mostly residential and as at 2008 household survey, generate 773.37 tonnes of waste annually. Major land use for the area is residential and agricultural with little commercial activity.

Research Design: A mixed research design which combined both survey and experimental methods was used for this study. This approach was appropriate for this study as the survey part of the analysis help to identify the sources and pathway of the release of microplastics and the key factors that influence this release, also it allows the review of the perception of people on the environmental and health impact of microplastics. By employing the experimental approach, we gained insights into ascertaining the presence of microplastics in the waste water of these recycling facilities.

Sample and Sampling Technique: A purposive and convenience sampling technique was used to select the companies to cover the various types of plastics recycled in the local government. Wash wastewater samples were collected from three advanced plastic recycling facilities located in the Alimosho. The first two specialize in collecting and recycling low-density polyethylene materials, such as packaging and waste bin nylons, to produce final products. The third facility focuses on the collection, crushing, and washing of high-density polyethylene materials, which are then exported for final use. Questionnaire survey was also employed using convenience sampling technique which involves using respondents who are available and willing to respond.

Figure 1: Alimosho Local Government Area showing the Sampling Locations Source: Author (2024)

Research Instrument: A Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy was utilised to identify microplastics in the wastewater samples. The method relies on detecting functional groups present in molecules, which undergo vibrations, either stretching or bending, when exposed to particular wavelengths of light. These vibrations and their intensity percentage transmission are plotted against the frequency of light measured in cm1 to generate an FTIR spectrum. Certain portions of the FTIR spectrum are distinctive to the compound being analyzed, known as the fingerprint region. The questionnaire employed in this research served as a pivotal tool designed to comprehensively gather pertinent data aimed at understanding the multifaceted dynamics of microplastic release, waste management practices, and the potential impact on the environment and public health within the scope of selected recycling facilities in Alimosho LGA.

Procedure for Data Collection

Samples from the wash water discharge flow paths within the recycling facilities, as they are expected to reflect the microplastics discharge from the sites, are collected, with the assumption that wash water constitutes a mixed, homogeneous discharge, although unmonitored. The wash water is used to wash grinded plastics to remove soil, grime, and general dirt from them for either packaging or to go on for pelletizing. At the discharge points, 2-litre water samples are collected. While collecting the water samples, the containers were filled without overflowing, thereby reducing the risk of any spillage from the glass containers during transport and related contamination. This also ensures that no floating microplastic particles are lost due to overflow. The collected samples were stored in a dark refrigerator at 4°C until they are ready for analysis[7]. A standard questionnaire form, consisting of 30 questions, was applied using convenience sampling method with face-to-face technique using participants from the three recycling facilities.

Procedure for Data Analysis

Analyzing Using the Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR)

Samples were separated by sieving with various mesh sizes. Distilled water was used to rinse the particles from the sieve and collect them in a labeled container. The sample was transferred into a beaker, then 30 mL of 4 Molar KOH (Potassium Hydroxide) solution was added and mixed by spinning at 350 rpm for 1 hour. Afterward, 5 mL of 30% hydrogen peroxide was added and spin again at 350 rpm for 15 minutes. The mixture was filtered using filter paper and the final sample was analyzed using FTIR spectroscopy.

Analyzing Using SPSS

Quantitative data from respondents generated using the research questionnaire were analyzed to get answers to research questions two, three and four using SPSS version 25. Descriptive statistics like percentages were used to summarize the demographic characteristics of the respondents as well as objectives.

Ethical Consideration

All participants involved in the study, including recycling facility personnel and staff, provided informed consent. Clear and comprehensive information about the study’s purpose, procedures, potential risks, and benefits were provided before they agreed to participate. It’s important to note that their participation was entirely voluntary, free from any coercion or pressure, and they retained the right to withdraw from the study at any point without facing consequences. Throughout the research process, scientific integrity was prioritized, meticulously ensuring the accuracy of data collection, analysis, and reporting.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1 Demographic Characteristics of the Respondents

The demographic characteristics of the respondents showed that out of 30 distributed questionnaires 25 was returned as presented in Table 1. Majority of the respondents were male, an indication that the recycling facilities are male dominated. The highest number of workers were between the ages of 18 – 28 and 29 – 39 years. In addition, majority of them had only 1 – 5 years working experience. The respondents are involved in different units of recycling operations with about 44% of the respondents been in sorting department, whereas shredding, washing, manager, baler and supervisor departments respectively are seen to make up a reasonably percentage (24%, 8%, 12%, 8% and 4%) of the variable.

Table 1: Demographic Characteristics of the Population

| Categories | Frequency | Percentage (%) | ||

| 1 | Recycling Facility | A | 9 | 36 |

| B | 8 | 32 | ||

| C | 8 | 32 | ||

| 2 | Age | 18 – 28 | 11 | 44 |

| 29 – 39 | 11 | 44 | ||

| 40 – 50 | 3 | 12 | ||

| 3 | Gender | Male | 17 | 68 |

| Female | 8 | 32 | ||

| 4 | Unit of Operation | Sorting | 11 | 44 |

| Shredding | 6 | 24 | ||

| Washing | 2 | 8 | ||

| Manager | 3 | 12 | ||

| Baler | 2 | 8 | ||

| Supervisor | 1 | 4 | ||

| 5 | Years of experience in recycling business | 1 – 5 years | 15 | 60 |

| 6 – 10 years | 10 | 40 |

3.2 Presence of Microplastics in the Wastewater of the Selected Recycling Facilities

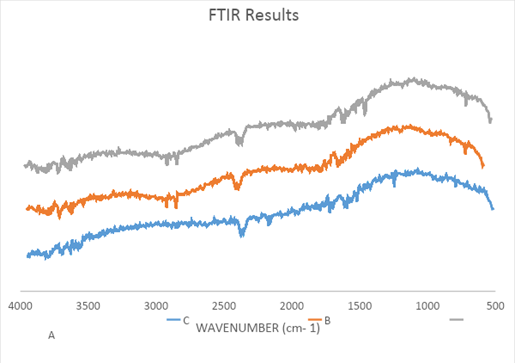

The Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) result from Figure 2 obtained from selected recycling facilities revealed the presence of distinct microplastics, Polyethylene Terephthalate (PET) in RFC, High-Density Polyethylene (HDPE) in RFB, and Low-Density Polyethylene (LDPE) in RFA, from the analysis of wastewater samples collected from the selected recycling facilities.

The presence of peaks at 1720 cm-1 (C = O stretching vibration of the carbonyl group), 1245 cm-1 (C – O stretching vibration of the ester group), and 795 cm-1 (C – H bending vibration of the aromatic ring) from the FITR spectrum confirmed the identification of PET microplastics in the wastewater of recycling facility RFC. This finding suggests that products made from PET, such as beverage containers, contribute to the microplastic content in this facility’s wastewater.

The FTIR analysis of wastewater from Factory RFB revealed peaks characteristic of HDPE microplastics due to the presence of peaks at 2920 cm-1 (C-H stretching vibration of the methylene group), 2850 cm-1 (C-H stretching vibration of the methyl group), 1460 cm-1 (C-H bending vibration of the methylene group), and 720 cm-1 (Rocking vibration of the methyl group). This indicates the prevalence of HDPE microplastics commonly used in packaging and containers.

FTIR spectrum for wastewater from RFA displayed characteristic peaks associated with LDPE microplastics from their wastewater. Peaks at 2917 cm-1 (C-H stretching vibration of the methylene group), 2848 cm-1 (C-H stretching vibration of the methyl group), 1463 cm-1 (C-H bending vibration of the methylene group), and 720 cm-1 (Rocking vibration of the methyl group). LDPE, commonly used in packaging films and bags, contributes significantly to the microplastic load in the environmental samples.

Figure 2: FTIR Results Indicating the Presence of Microplastics in the Wash Wastewater of The Three Recycling Facilities

Key: A – Recycling Facility A (RFA), B – Recycling Facility B (RFB), C – Recycling Facility C (RFC)

Remarkably, all three samples’ FTIR spectra showed peaks at 2920 cm-1 and 2850 cm-1, suggesting that the methylene and methyl groups’ C-H stretching vibrations were present. These vibrations are frequently detected in a variety of plastic polymers, indicating a common source or contributing elements in these facilities’ recycling procedures. According to a study by [8], a cutting-edge Plastic Recycling Facility (PRF) in the United Kingdom releases 22,680 tonnes of mixed plastic waste into the aquatic environment annually. Microplastics were discovered in the facilities’ effluent outputs, suggesting that they are not being sufficiently eliminated during the recycling process. The amount and size of microplastics released were similar to those discovered in surface water and wastewater treatment facilities, indicating that mechanical recycling is a significant source of microplastic pollution. Additionally, [9] discovered that the wastewater had a high concentration of microplastics with an estimated 75 billion microplastics per cubic meter of wastewater per year.

3.3 Sources and Pathways of Microplastic release into the Environment

3.3.1 Recycling Participation Rates

The data revealed varying levels of awareness among respondents regarding microplastic issues stemming from the recycling process, Table 2. While a significant percentage across all facilities affirmed their participation in regular recycling activities, a notable proportion lacked prior information regarding microplastic release from recycling processes. Specifically, 44.4 % from RFA, 37.5% from RFB, and 25% from RFC expressed awareness of the issue, while a higher percentage in each facility indicated a lack of prior information. A substantial majority of respondents across all facilities believed that the recycling process at their respective facilities might contribute to microplastic release into the environment. The perception was notably strong in RFA (77.8 %), RFB (75.0%), and RFC (75.0 %), indicating an acknowledgment of potential microplastic releases from their recycling operations. Respondents largely denied observing visible signs of microplastics pollution around the facilities. However, a fraction from RFC (12.5%) confirmed witnessing possible signs of pollution associated with microplastics.

Table 2: Percentage Distribution of Respondents to “Recycling participation rates

| S/N | VARIABLE | RFA (%) | RFB (%) | RFC (%) | |||

| YES | NO | YES | NO | YES | NO | ||

| 1 | Do you regularly participate in recycling activities? | 100 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 100 | 0 |

| 2 | Are you aware of the issue of micro plastics being released from recycling processes? | 44.4 | 56 | 37.5 | 63 | 25 | 75 |

| 3 | Do you believe that the recycling processes at your facility might release micro plastics into the environment? | 77.8 | 22 | 75 | 25 | 75 | 25 |

| 4 | Have you noticed any visible signs of environmental pollution near recycling facilities that could be linked to micro plastic release? | 0 | 100 | 0 | 100 | 12.5 | 88 |

3.3.2 Recycling Processes Employed

The predominant recycling processes identified included sorting, shredding, and washing, with additional variations such as extrusion, pelletization, and baling, particularly observed in RFA. Regarding the definition of microplastics, a considerable number of respondents identified multiple definitions, highlighting varied interpretations ranging from plastic particles smaller than 5 mm [12] to microscopic plastic particles found in the environment. Moreover, respondents primarily associated microplastics with the shredding process within their facilities as a potential source of release. In a study by [10] noted that the size reduction phase, specifically mechanical shredding, was identified as the primary source of microplastic generation. Respondents predominantly perceived recycling facilities as potential sources of microplastics in the environment. A smaller percentage attributed it to plastic manufacturing processes, while waste mismanagement was also indicated as a contributing factor. The majority of respondents from all facilities believed that Wash wastewater discharge is the primary pathway for microplastic release into the environment from recycling facilities. This is in line with study carried out by [11] indicating that the profiles of microplastics in samples from production wastewater, effluents, and sludge from a plastic recycling facility in China showed significant differences A fraction from RFC (12.5 %) considered airborne emissions as a potential route, and a negligible percentage believed it could occur through waste runoff as presented in Table 3 below. A unanimous consensus (100 %) was observed among respondents from all three facilities, identifying shredding as the primary practice contributing to microplastic release. Sorting, shredding, and washing were reported as standard practices in managing plastic waste across all the facilities. Additionally, a fraction from RFA (22 %) included melting in the process of pelletizing.

Table 3: Perception of people on the Recycling Processes Employed in the three Facilities

| S/N | Variable | Options | ||||

| RFA (%) | RFB (%) | RFC (%) | ||||

| 1 | What type of recycling processes do you or your company employ? | Sorting, Shredding, Washing | 0 | 100 | 100 | |

| Sorting, Shredding, Washing, Extrusion, Pelletization | 44.4 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Sorting, Shredding, Washing, Extrusion, Pelletization, baling | 55.6 | 0 | 0 | |||

| 2 | How do you become aware of issues of microplastic? | Research | 33.3 | 0 | 0 | |

| News | 0 | 12.5 | 0 | |||

| Training | 11.1 | 25 | 25 | |||

| Missing | 55.6 | 62.5 | 75 | |||

| 3 | How would you define micro plastics? | Fragments of any type of plastic less than 5 mm in length | 33.3 | 12.5 | 37.5 | |

| Microscopic plastic particles found in the environment | 11.1 | 25 | 25 | |||

| All of the above | 55.6 | 62.5 | 37.5 | |||

| 4 | Can you briefly describe the potential sources or processes within your facility that may contribute to micro plastic release? | Shredding | 77.8 | 75 | 75 | |

| Other processes (Sorting, Washing, Extrusion, Pelletization, baling) | 22.2 | 25 | 25 | |||

| 5 | Where do you think micro plastics come from in the environment? | Plastic manufacturing | 11.1 | 12.5 | 12.5 | |

| Recycling facilities | 77.8 | 50 | 75 | |||

| Waste mismanagement | 11.1 | 37.5 | 12.5 | |||

| 6 | How do you believe micro plastics are released into the environment from recycling facilities? | Airborne emissions | 0 | 0 | 12.5 | |

| Wash Wastewater discharge | 88.9 | 87.5 | 75 | |||

| Waste runoff | 11.1 | 12.5 | 12.5 | |||

Key: RFA: Recycling Facility A, RFB: Recycling Facility B, RFC: Recycling Facility C

3.4 Key Factors that Influence the Release of Microplastics by Recycling Facilities

3.4.1 Familiarity with Operational Processes

The investigation into factors influencing microplastic release by recycling facilities revealed several critical insights based on the survey responses collected from RFA, RFB and RFC participants (Table 4). All respondents across the three facilities acknowledged their familiarity with recycling processes. Interestingly, a substantial proportion from RFA (88.9 %), RFB (100 %), and RFC (87.5 %) believed that these processes could contribute to microplastic release. A minority from RFA (11 %), and RFB (12.5 %) expressed doubts about the process contributing to microplastics. The awareness of existing regulations varied among the facilities, with more respondents from RFA acknowledging their existence compared to RFB and RFC. However, the majority across all facilities either denied the presence of regulations or lacked awareness. Among those acknowledging regulations, only a small fraction from RFA (11.1 %) perceived them as effective in mitigating microplastic release.

Table 4: Percentage Distribution of Respondents to “Familiarity with the Operational Process and Regulations that Influences Release of Microplastic

| S/N | VARIABLE | RFA (%) | RFB (%) | RFC (%) | |||

| YES | NO | YES | NO | YES | NO | ||

| 1 | Are you familiar with the operational processes of recycling facilities? | 100 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 100 | 0 |

| 2 | Do you believe these processes contribute to micro plastic release? | 88.9 | 11 | 100 | 0 | 87.5 | 13 |

| 3 | Are there existing regulations or guidelines for recycling facilities in managing micro plastic release? | 33.3 | 66.7 | 12.5 | 87.5 | 25 | 75 |

| 4 | If yes, do you think these regulations are effective in mitigating micro plastic release? | 11.1 | 33.3 | 0 | 12.5 | 25 | |

3.4.2 Operations that could Influence and Strategies to Mitigate Microplastic Release

The findings underscore the consensus among respondents regarding the potential contribution of recycling processes, especially shredding, to microplastic release. Moreover, the varied perceptions on the effectiveness of regulations and proposed improvement strategies indicate a need for comprehensive measures, public engagement, and stricter regulations to mitigate microplastic release from recycling facilities. In a study by [12] it was indicated that the type of plastics recycled can influence the abrasion resistance and fragmentation potential, leading to varying levels of microplastic generation during processing. The specific processing steps within the facility, such as shredding, washing, and separation techniques, can also contribute to microplastic release through mechanical fragmentation or abrasion.

Respondents suggested various strategies for reducing microplastic release. Implementation of advanced filtration systems garnered support from a portion of respondents across all facilities. Conducting regular maintenance and cleaning of recycling equipment was also deemed essential. Some respondents highlighted the importance of promoting responsible plastic handling, ensuring proper containment, proper disposal of waste materials, and conducting regular maintenance as crucial improvement strategies. The perception of the importance of public awareness in minimizing microplastic release varied among respondents. A significant portion believed public involvement was somewhat important or very important, recognizing the need for public engagement in mitigating microplastic release from recycling facilities. It has been highlighted in various studies [13] that the mechanical shredding of plastic waste is the primary source of microplastic generation. Other phases of the recycling process, such as sorting and washing, may also contribute to microplastic release. The specific practices used at a recycling facility can influence the amount of microplastics released. For example, using shredders with smaller blades or reducing the speed of the shredding process can help to reduce microplastic generation.

Table 5: Perception of Operations that could Influence and Mitigate Microplastic Release

| Variable | Options | RFA (%) | RFB (%) | RFC (%) | |

| 1 | Specify any operational process that might contribute majorly to micro plastic release in RF | Shredding | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Total | 100 | 100 | 100 | ||

| 2 | How do you think recycling facilities manage plastic waste? | Sorting, Shredding, Washing | 77.8 | 100 | 100 |

| Sorting, Shredding, Washing, Melting | 22.2 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Total | 100 | 100 | 100 | ||

| 3 | In your opinion, what improvements or technologies could be adopted by recycling facilities to reduce micro plastic release? | Implementation of advanced filtration systems | 33.3 | 37.5 | 37.5 |

| Conducting regular maintenance and cleaning of recycling equipment | 33.3 | 62.5 | 50 | ||

| Promotion of responsible plastic handling and recycling practices | 11.1 | 0 | 12.5 | ||

| Ensuring proper containment and disposal of waste materials | 22.2 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Total | 100 | 100 | 100 | ||

| 4 | How important do you think public awareness and involvement are in minimizing micro plastic release from recycling facilities? | Not important | 22.2 | 25 | 12.5 |

| Somehow Important | 55.6 | 50 | 62.5 | ||

| Very important | 22.2 | 25 | 25 | ||

| Total | 100 | 100 | 100 |

4.5 Potential Environmental and Health impacts of Microplastics in Alimosho Local Government.

Table 6 presents the interpretation of survey responses pertaining to the environmental and health impacts of microplastics in Alimosho Local Government revealing perceptions and awareness regarding potential hazards associated with microplastics.A majority of respondents (80%) expressed agreement (56% agree, 24% strongly agree) that microplastics pose harm to wild and aquatic life. This substantial agreement underscores the perceived threat that microplastics pose to ecosystems and biodiversity, indicating awareness of the detrimental effects on wildlife and aquatic organisms.Regarding the potential contamination of agricultural soil by microplastics, a significant proportion (84%) agreed (52% agree, 32% strongly agree) that agricultural soil could be polluted by microplastics. This awareness emphasizes concerns about the potential agricultural ramifications and soil health implications attributed to microplastic pollution.

Respondents displayed varied perceptions regarding the health risks posed by microplastics to humans. While a considerable percentage agreed (60%) and strongly agreed (12%) that microplastics pose health risks to humans, a combined 28% disagreed or strongly disagreed with this notion. This disparity in perceptions regarding human health risks associated with microplastics suggests a lack of consensus or awareness regarding this aspect among respondents. This is not in agreement with study by [14]which indicated that microplastics can carry dangerous chemicals and other substances, causing serious health hazards when they enter the human body through inhalation, ingestion, or skin contact, causing various health hazards, including cell injury, hormone disruption, and cardiovascular disease.

A significant majority (80%) concurred (64% agree, 16% strongly agree) that microplastics released from recycling facilities significantly contribute to water and soil pollution. This acknowledgment highlights the perceived role of recycling facilities as a significant source of environmental pollution due to microplastics. According to [15]microplastics contribute to the spread of pathogens, it reduces the quality of drinking water and interferes with the effectiveness of wastewater treatment plants.

Regarding the perception of microplastics as a pressing concern for the local community, a majority (92%) expressed agreement (52% agree, 40% strongly agree). This alignment indicates a widespread belief in the significance of microplastics as a pertinent issue demanding attention within the local context.

A majority (106%) of respondents agreed (58% agree, 48% strongly agree) that implementing adequate measures to control the release of microplastics could significantly mitigate environmental and health risks. This agreement underscores the perceived efficacy of proactive measures in mitigating the adverse impacts of microplastics. Microplastics contribute to the spread of pathogens, it reduces the quality of drinking water and interferes with the effectiveness of wastewater treatment plants and can also absorb and concentrate harmful chemicals, which can then be transferred up the food chain [16].

Table 6: Percentage Distribution of Respondents to “The Environmental and Health Impacts of Microplastics in Alimosho Local Government.”

| Variables | Options | RFA (%) | RFB (%) | RFC (%) | |

| 1 | It is true that microplastics pose harm to wild and aquatic life | Strongly agree | 44.4 | 25 | 0 |

| Agree | 55.6 | 37.5 | 75 | ||

| Disagree | 0 | 37.5 | 25 | ||

| Strongly Disagree | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Total | 100 | 100 | 100 | ||

| 2 | It is true that micro-plastics can contaminate agricultural soil | Strongly agree | 33.3 | 50 | 12.5 |

| Agree | 66.7 | 25 | 62.5 | ||

| Disagree | 0 | 25 | 25 | ||

| Strongly Disagree | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Total | 100 | 100 | 100 | ||

| 3 | I am aware that microplastics pose health risks to humans | Strongly agree | 22.2 | 12.5 | 0 |

| Agree | 77.8 | 37.5 | 62.5 | ||

| Disagree | 0 | 25 | 25 | ||

| Strongly Disagree | 0 | 25 | 12.5 | ||

| Total | 100 | 100 | 100 | ||

| 4 | Micro-plastics released from recycling facilities significantly contribute to water and soil pollution. | Strongly agree | 11.1 | 12.5 | 25 |

| Agree | 88.9 | 50 | 50 | ||

| Disagree | 0 | 25 | 25 | ||

| Strongly Disagree | 0 | 12.5 | 0 | ||

| Total | 100 | 100 | 100 | ||

| 5 | The environmental impact of released microplastics from recycling facilities is a pressing concern for the local community. | Strongly agree | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Agree | 77.8 | 25 | 50 | ||

| Disagree | 11.1 | 12.5 | 50 | ||

| Strongly Disagree | 11.1 | 62.5 | 0 | ||

| Total | 100 | 100 | 100 | ||

| 6 | Adequate measures to control micro-plastic release from recycling facilities can significantly minimize environmental and health risks. | Strongly agree | 22.2 | 75 | 50 |

| Agree | 77.8 | 25 | 50 | ||

| Disagree | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Strongly Disagree | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Total | 100 | 100 | 100 |

Conclusion

The comprehensive investigation into microplastic presence within wastewater from three selected recycling facilities provided crucial insights into the types and sources of microplastics in the Alimosho local government area. The Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) analysis unveiled distinct microplastics, Polyethylene Terephthalate (PET) in RFC, High-Density Polyethylene (HDPE) in RFB, and Low-Density Polyethylene (LDPE) in RFA. These findings align with established characteristics of these plastics, implicating specific products and packaging as significant contributors to microplastic pollution. The study delved further into understanding the awareness, perceptions, and practices of individuals within these facilities regarding microplastic issues. Despite significant participation in recycling activities, a notable portion lacked prior knowledge about microplastic release from recycling processes. However, there was a widespread acknowledgment among respondents that their facilities could potentially contribute to microplastic emissions. The consensus primarily pointed to the shredding process as a significant source of microplastic release, with recycling practices involving sorting, washing, and additional processes contributing to the environmental burden. Respondents’ awareness of microplastics’ environmental and health impacts varied but indicated substantial concern about their detrimental effects on wildlife, aquatic life, soil, and community health. The agreement on the significance of microplastics as a pressing local concern and the belief in the effectiveness of measures to control their release underscores the necessity for proactive strategies, stricter regulations, and heightened public awareness to mitigate these risks effectively. The results highlight the urgent need for stringent measures within recycling facilities to curb microplastic release and the imperative role of public engagement in addressing this environmental challenge. Additionally, it calls for enhanced regulations, improved recycling practices, and ongoing research to develop more efficient recycling methods and minimize the environmental footprint of these facilities. This study serves as a pivotal foundation for initiating focused interventions and policy considerations aimed at reducing microplastic pollution originating from recycling facilities within the Alimosho local government area, in Lagos State ultimately contributing to the larger global effort to safeguard our environment and public health.

5. Recommendations

Recycling facilities should explore alternative methods to reduce microplastic release, potentially minimizing reliance on shredding or implementing advanced filtration systems during the shredding process. They should implement stringent regulations governing microplastic release in the recycling process. These guidelines should be enforced effectively, ensuring responsible waste management and pollution control. Public awareness campaigns should emphasize the dangers of microplastics and promote responsible recycling practices. Training programs for recycling facility staff can foster a deeper understanding of microplastic pollution and its mitigation. Continuous monitoring and research initiatives are essential to gauge the evolving impact of microplastics, aiding in devising adaptive strategies for mitigation.

The cumulative impact of microplastics on the environment and human health demands urgent attention. Implementing these recommendations will fortify the journey towards sustainable practices, preserving our environment and safeguarding community well-being from the detrimental effects of microplastic pollution.

REFERENCES

- Lamichhane, G., Acharya, A., Marahatha, R., Modi, B., Paudel, R., Adhikari, A., Raut, B. K., Aryal, S., & Parajuli, N. (2022). Microplastics in environment: Global concern, challenges, and controlling measures. International Journal of Environmental Science and Technology, 20, 4673 – 4694. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13762-022-04261-1.

- Suzuki, G., Uchida, N., Tuyen, L. H., Tanaka, K., Matsukami, H., Kunisue, T., Takahashi, S., Viet, P. H., Kuramochi, H., and Osako, M. (2022). Mechanical recycling of plastic waste as a point source of microplastic pollution. Environmental Pollution, 303, 119114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2022.119114.

- Faleti, Ayodele. (2022). Microplastics in the Nigerian Environment- A review. 10.26434/chemrxiv-2022-n2xk8-v2.

- Ikpoto, E. (2023). Lagos battles plastic pollution amid $2bn recycling industry. Punch Newspapers. https://punchng.com/lagos-battles-plastic-pollution-amid-2bn-recycling-industry/

- Stapleton, M. J., Ansari, A. J., Ahmed, A., & Hai, F. I. (2023). Evaluating the generation of microplastics from an unlikely source: The unintentional consequence of the current plastic recycling process. Science of the Total Environment, 902, 166090–166090. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.166090

- Akoteyon. I. S., Mbata, U. A. and Olalude G. A. (2011). Investigation Of Heavy Metal Contamination in Groundwater Around Landfill Site in a Typical Sub-Urban Settlement in Alimosho, Lagos-Nigeria. Journal of Applied Sciences, Environment and Sustainable, 6(2); 156 – 163.

- Bayo, J., López-Castellanos, J., & Olmos, S. (2020). Membrane bioreactor and rapid sand filtration for the removal of microplastics in an urban wastewater treatment plant. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 156, 111211. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpolbul.2020.111211

- Erina Brown, Anna MacDonald, Steve Allen, Deonie Allen, (2023). The potential for a plastic recycling facility to release microplastic pollution and possible filtration remediation effectiveness, Journal of Hazardous Materials Advances, Volume 10, 100309, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hazadv.2023.100309.

- Brown, E., MacDonald, A., Allen, S., & Allen, D. (2023). The potential for a plastic recycling facility to release microplastic pollution and possible filtration remediation effectiveness. Journal of Hazardous Materials Advances, 10, 100309. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hazadv.2023.100309.

- Almroth, B., Carmona, E., Chukwuone, N., Dey, T., Slunge, D., Backhaus, T., and Karlsson, T., (2025). Addressing the toxic chemicals problem in plastics recycling. Cambridge Prisms: Plastics. 3. 1-20. 10.1017/plc.2025.1.

- Yuwen Guo, Xinyue Xia, Jiuli Ruan, Yibo Wang, Jinyu Zhang, Gerald A. LeBlanc, Lihui An (2022). Ignored microplastic sources from plastic bottle recycling. Science of The Total Environment, Volume 838, Part 2,156038, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.156038.

- Goswami S, Adhikary S, Bhattacharya S, Agarwal R, Ganguly A, Nanda S, Rajak P. (2024). The alarming link between environmental microplastics and health hazards with special emphasis on cancer. Life Sci. 15; 355: 122937. doi:10.1016/j.lfs.2024.122937.

- Altieri, V.G., De Sanctis, M., Sgherza, D., Pentassuglia, S., Barca, E., Di Iaconi, C. (2021). Treating and reusing wastewater generated by the washing operations in the non-hazardous plastic solid waste recycling process: advanced method vs. conventional method. J. Environ. Manage., 284, 0301 – 4797 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2021.112011.

- Lalrinfela, P., Vanlalsangi, R., Lalrinzuali, K., Babu, P. (2024). Microplastics: Their effects on the environment, human health, and plant ecosystems. Environmental Pollution and Management, 1, 248 – 259. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epm.2024.11.004.

- Campanale, C., Massarelli, C., Savino, I., Locaputo, V., & Uricchio, V. F. (2020). A Detailed Review Study on Potential Effects of Microplastics and Additives of Concern on Human Health. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(4), 1212. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17041212

- Kehinde, O., Ramonu, O. J., Babaremu, K. O., & Justin, L. D. (2020). Plastic wastes: environmental hazard and instrument for wealth creation in Nigeria. Heliyon, 6(10). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e05131

- J. S. Attah, H. O. Stanley, F. D. Sikoki, and O. M. Immanuel. “Assessment of Microplastic Pollution in Selected Water Bodies in Rivers State, Nigeria”. Archives of Current Research International 2023; 23(7):45–52. https://doi.org/10.9734/acri/2023/v23i7591.

- Nweke, N.D., Agbasi, J.C., Ayejoto, D.A., Onuba, L.N., Egbueri, J.C. (2024). Sources and Environmental Distribution of Microplastics in Nigeria. In: Egbueri, J.C., Ighalo, J.O., Pande, C.B. (eds) Microplastics in African and Asian Environments. Emerging Contaminants and Associated Treatment Technologies. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-64253-1_6