Introduction

Carbon dioxide emission (CO2) during the manufacture of cement is the main anthropogenic contributor to global warming [1-3]. Global warming may lead to human casualties and substantial economic losses [3, 4]. To minimize CO2 emissions from cement industry, the ceramic sludge ash (CSA) could be used as a supplementary cementitious material (SCM), which is partially replacing to cement to form suitable cement pastes particularly as Portland cement clinker (PCC) that has similar constituents with CSA [5-12]. Recently, several studies had investigated the utilization of CSA. The fineness of CSA waste particles is too high to be nanoparticles that facilitate its reutilization it blended cement [13]. The porous matrix caused by the addition of CSA demonstrated its lower fluidity in cementitious mortar [14-16]. Some studies showed that CSA increased the setting of cement pastes [17-21]. The cement dilution influences the early strength of cementitious mortar, and with a lower effect on the long-term strength [22-24]. When the hydration proccedes, the pozzolanic reactions of CSA with portlandite started and form more C-S-H-gel that compensated the loss of initial strength which is mainly attributed to decline of early hydration reaction by orthophosphate from CSA in the pore solution [25-27]. Existence of more inert materials in CSA could be negatively effective. This is the main cause that influencing the early hydration, Pozzolanic reactions during the later ages of hydration showed that the high SiO2 materials affected the amount and type of the formed C-S-H. This influenced the characteristics of cements, i.e. fluidity, porosity and strength. It is essentially attributed to the easy reaction of SiO2 when present in alkaline media with Ca (OH)2. Thus, CSA has more SiO2, Al2O3 and CaO contents [28-31]. So, CSA was shown to be effective and necessary and the investigation of CSA effect on the long run strength of cement paste by determining of the pozzolanic reaction is too important to study [32-36]. Hence, the pozzolanic reactions comprise heat release, bound water, and/or portlandite consumption serves as a reliable indicator [29-33]. Relation among heat release and Ca (OH)2 consumption depends on the chemical composition of the pozzolan itself. The objective of the current research is to show the effect of the CSA waste material on the various properties of the OPC pastes. Results are confirmed by the free lime content, heat of hydration and scanning electron microscopy (SEM).

Test procedures

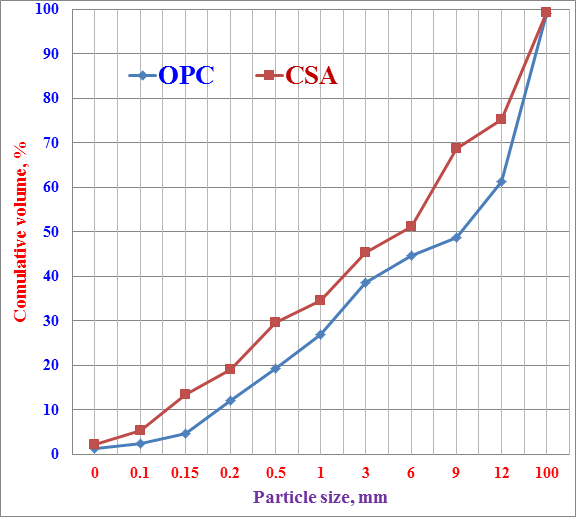

Used raw materials in the research article are Ordinary Portland cement (OPC) which was supplied from Sakkara cement factory, Egypt. Elementary phases of the OPC are tabulated in Table 1, while oxide ratios of OPC and ceramic sludge ash (CSA), as analyzed by an X-ray fluorescence (XRF) are summarized in Table 2. Basically physical features of the OPC cement and CSA waste material are shown in Table 3. At first, CSA was dried and kept at 100 °C for two days. CSA waste was calcined in a furnace up to 800 ℃ for 2 hours. Then, it was put into a ball mill for 2 minutes to obtain CSA [24-26]. Particle size distribution of both OPC and SSA are shown in Fig. 1, where the CSA is the higher fineness, whereas the OPC is the lower. Table 4 shows the constitutions of the various cement mixtures. The CSA was substituted for cement to prepare cement mixtures.

Table 1- Phase constituents of Cement spacemen, %.

| Phase Material | C3S | β-C2S | C3A | C4AF |

| OPC | 49.47 | 29.19 | 4.83 | 11.85 |

Table 2- Chemical composition of materials (%)

| Oxides Materials | SiO2 | Al2O3 | Fe2O3 | CaO | MgO | Na2O | K2O | SO3 | LOI | Total |

| OPC | 21.24 | 4.68 | 2.87 | 63.32 | 2.01 | 1.23 | 0.68 | 2.06 | 1.76 | |

| CSA | 56.12 | 17.26 | 7.88 | 9.22 | 3.29 | .0.96 | 2.98 | 1.60 | 1.65 |

Table 3- Physical properties of raw materials, %

| Properties Materials | Spec. gravity | Density, g/cm3 | Fineness, cm2/g |

| OPC | 3.15 | 3.12 | 3564 |

| CSA | 2.66 | 2.87 | 5683 |

Table 4- Composition of cement mixtures, wt. %

| Mixtures Materials | S0 | S1 | S2 | S3 | S4 | S5 | S6 | S7 |

| OPC | 100 | 95 | 90 | 85 | 80 | 75 | 70 | 65 |

| CSA | 0 | 5 | 10 | 15 | 20 | 25 | 30 | 35 |

Fig. 1-Particle size distribution of raw OPC and CSA.

During the preparation of cement mixtures, different dosages of CSA (0, 5, 10, 15, 20, 25, 30 and 35 wt. %) were added to the OPC. These OPC/CSA mixtures were categorized into nine groups as C0, C1, C2, C3, C4, C5, C6 and C7, respectively. Mixing of the various cement blends has done in a porcelain ball mill containing 3-5 balls for one hour to assure the complete homogeneity of blends. Firstly, the w/c-ratio and setting time are measured using Vicat apparatus [37-39]. Pastes of the various blends were prepared with the determined w/c-ratio, i.e. the right w/c-ratio was added to the cement powder in the mixer. Then, the mixer was run for about 5 minutes at an average speed of 10 rpm to have a perfect homogenous mixture. Cement pastes were then molded into one inch cubic stainless steel molds (2.5 cm3) using about 500 g cement mix, vibrated manually for two min. and then on a mechanical vibrator for another two min. [32]. The surface of the molds was smoothed using a suitable spatula. The molds were kept in a humidity cabinet for 24 hrs. on 95±2 RH and R.T of 20 ± 1 ℃ for curing until the corresponding days. In the following day, the molds were demolded and the samples were immediately placed in water till the time of testing. Water absorption, bulk density and total porosity[40,41] of the hardened cement pastes could be calculated.

Flexural strength (FS) was calculated [42,43], whereas the samples were marked at three points adjusting to place them on the correct point of contact (Fig. 2). The compressive strength of the different cement pastes also was measured (44,45).

Fig. 2- Schematic diagram of bending strength, B: Beam or loading of rupture, S: Span, W: Width and T: Thickness.

Free lime (FLn) of the hydrated specimens pre-dried at 105°C for 24h was also measured [32,45-49]. Heat of hydration has been studied to assure the obtained results [50-53]. Ultra-sonic pulse velocity (UPV) was essentially done. Based on the measured free lime contents, the degree of cement hydration was explored the influence of CSA on the long-term strength of cement pastes.

The X-ray fluorescence (XRF) was analyzed the chemical and phase composition of OPC and CSA, identifying crystalline phases of OPC cement. Constituents of some samples were studied with scanning electron microscopy (SEM). The SEM images of the fractured surfaces, coated with a thin layer of gold, were obtained by JEOL-JXA-840 electron analyzer at accelerating voltage of 30 KV. The arithmetic mean for each group could be determined the corresponding strength values, noting that any abnormal data must be excluded.

Results and Discussion

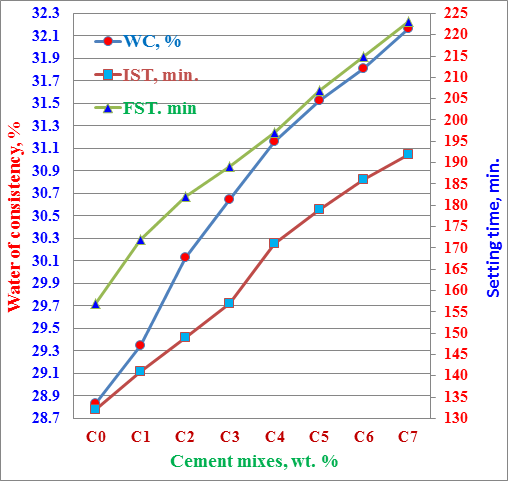

Water of consistency (WC) and setting times (ST) of OPC pastes (C0) blended with various percentages of CSA (C1-C7) are shown in Fig. 2. It is clear that WC of the control (S0) was 28.83 %. This value was increased as the content of CSA enhanced. Also, the ST (Initial and final) of the blank (C0) were 132 and 157 min. respectively. These values were enhanced as the CSA content enhanced. It is mainly contributed to the high fineness of CSA material [54-57]. Furthermore, the pozzolanicity of the CSA with the produced portlandite, which is in need to more water to occur [46,56-60].

Fig. 2- Water of consistency and setting time of OPC pastes mixed with CSA.

Physical characteristics

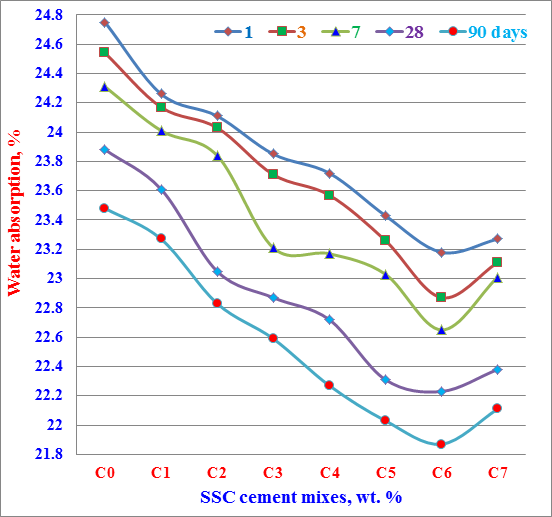

Water absorption (WA) of OPC cement pastes blended with various contents of CSA hydrated up to 90 days are represented in Fig. 3. Results illustrated that the WA of control (C0) decreased all over hydration times. It is surely attributed to the mechanism of hydration of cement phases [37,57,61]. As CSA content increased, the WA decreased. This firstly may be attributed to the increased compaction of the hardened cement pastes due to the decreased pore volume. Furthermore, the pozzolanic property of CSA with the producing portlandite that was coming from the hydration of silicates phases of the cement help to decrease the WA [45,46,62]. This was continued till 30 wt. % CSA (C6). But, with any further CSA addition, the water absorption tended to increase (C7). This is essentially contributed to that the higher content of CSA at the expense of the main binding material negatively reflected on the WA results [32,46,56-58,63-65]. Accordingly, the higher content of the additive material must be refused.

Fig. 3-Water absorption of OPC pastes mixed with CSA hydrated till 90 days.

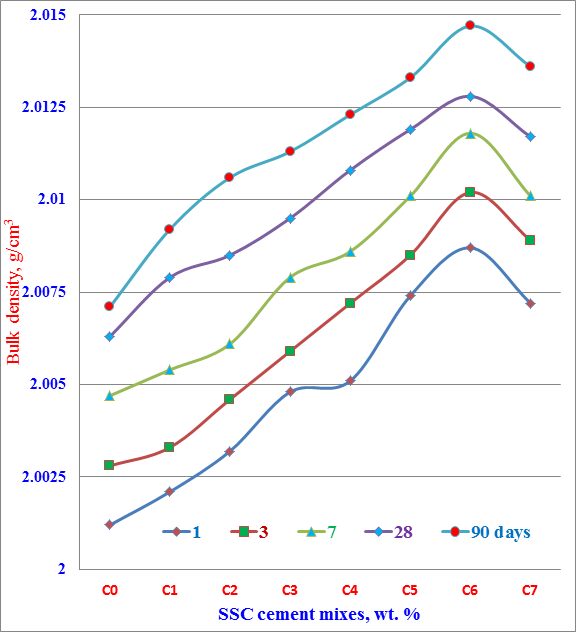

Figure 4 illustrates the bulk density (BD) of cement mixtures containing various ratios of CSA (C1-C7) compared to that of the control mixture (C0) hydrated up to 1, 7, 28 and 90 days. Results indicated that the BD increased as the content of CPSA increased [32,37,39,66]. This continued till the mix containing 30 wt. % (C6). With any increased addition of CSA › 30 wt. %, the BD tended to decrease. The increase of BD is due to the increased compaction by CSA which precipitated inside the pore volume of the specimens. This resulted to decrease the total porosity [45,46,56,67]. Therefore, the higher contents of CSA must be prevented.

Fig. 4-Bulk density of OPC pastes mixed with CSA hydrated till 90 days.

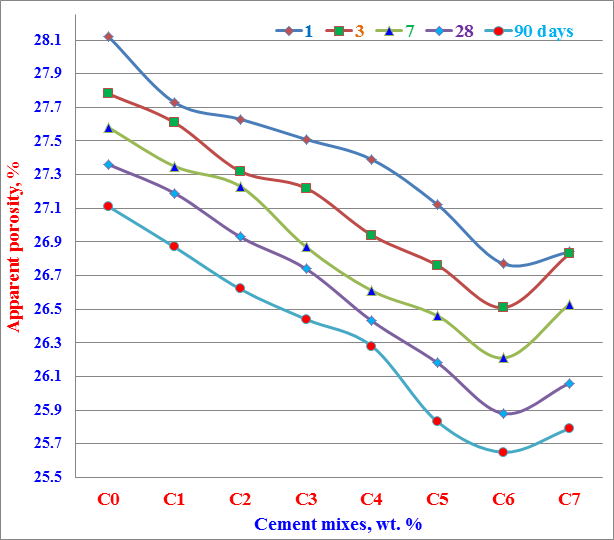

Total porosity (TP) of OPC cement pastes (C0) blended with various proportions of CSA (C1-C7) hydrated till 90 days are represented in Fig. 5. It is clearly that the TP decreased, while the hydration occurred till 90 days. Moreover, it also lowered with the increase of CSA content, but this continued merely up to 30 % (C6). Then, it enhanced with any other CSA addition. Decreasing of TP is mainly due to the pozzolanic properties of CSA with the produced portlanditethat is produced from the hydration of C3S and C2S phases of the cement [22,37,47]. But, the increased values of TP is mainly contributed to stopping of hydration that was resulting from the incorporation of larger amounts of CSA (C7), which decreased not only the normal hydration process, but also the pozzo;anic activity of CSA [68-70]. So, the higher quantities of CSA must be refused due to its adverse effect. Results of TP are in a good agreement with those of BD and WA to a large extent.

Fig. 5-Total porosity of OPC pastes mixed with CSA hydrated till 90 days.

Mechanical properties

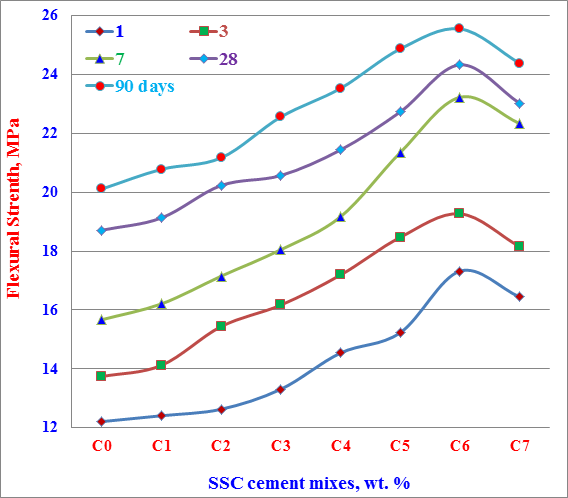

Results of flexural strength (FS) of OPC cement pastes (C0) mixed with various contents of CSA (C1-C7) hydrated till 90 days are demonstrated in Fig. 6. As shown from the figure, the FS increased as the hydration age increased up till 90 days. It is mainly due to the newly formed CSH products as a result of hydration, which improved FS of hardened cement pastes [37,69]. The FS also increased by the addition of CSA till 30 wt. % (C6), and then negatively influenced by any other addition of CSA (C7). The increased FS results with CSA addition are often attributed to the pozzolanic reactivity of CSA with the formed portlandite from the hydration of di- and tricalcium silicates phases (C3S and β-C2S) of the cement. Furthermore, unreacted CSA acted as a filler that closed the pore system of samples, i.e. the total porosity decreased [57,70,71]. The adverse results with the higher addition of CSA (C7) is principally due to that the high quantities of the additive material hindered and may be ceased the hydration of cement phases and helped to open the pore structure to a large extent [45-47]. Therefore, the higher amounts of the CSA must be removed.

Fig. 6-Flexural strength of OPC pastes mixed with CSA hydrated till 90 days.

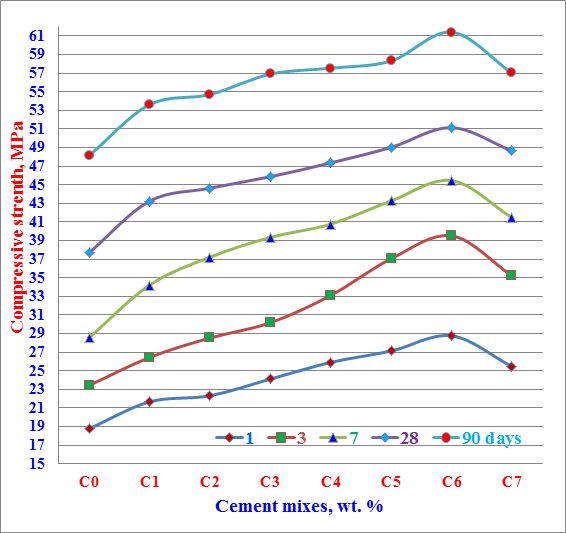

Compressive strength (CS) of hardened blank pastes (C0) mixed with different proportions of CSA (C1-C7) hydrated up 90 days is represented in Fig, 7. CS of hardened pastes enhanced with as the hydration age till 90 days. It is mainly due to the newly resulting CSH, which are precipitated into the pore volume, i.e. this decreased the TP and increased the BD. So, this could be inverted well on the CS of the cement pastes [37,45,67]. Also, crystal growth of the formed CSH was gradually improved and enhanced. The improvements of CS often enhanced with CSA addition, but merely till 30 wt. % (C6), and then adversely affected by any other addition of CSA (C7). Improved CS results with CSA addition are often due to the pozzolanic reactivity of CSA with the resuling portlandite from the normal hydration process of di- and tricalcium silicates (β-C2S and C3S) of cement, Furthermore, CSA improved the compaction of the constituents together, i.e. the pore structure was partially or completely closed. Unreacted CSA particles were acted as a filler that closed the pore system of samples [55,70,71]. The adverse results with the higher content of CSA (C7) were principally contributed to that the higher contents of the additive material largely stopped the hydration of cement phases. This helped to open more-pore structure to a large extent [32,45-47]. Therefore, the higher contents of CSA must be illuminated.

Fig, 7- Compressive strength of OPC pastes mixed with CSA hydrated till 90 days.

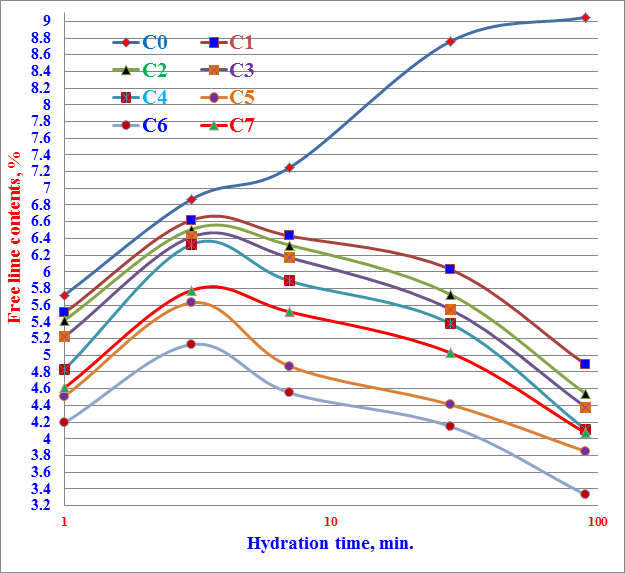

Free lime contents (FLn) or portlandite of blank cement pastes (C0) blended with various ratios of CSA (C1-C8) hydrated till 90 days are shown in Fig, 8. FLn of blank (C0) was enhanced little by little as the hydration period was going till 90 days. It is essentially contributed to the hydration of the main silicate phases of the cement [37,58,72-74]. Additionally, FLn of other blended cements incorporated different ratios of CSA increased till 7 days of hydration, but then it began to reduce down to 90 days. It is fundamentally contributed to the pozzolanic phenomenon which could be occurred among the resulting free line and CSA particles [64-66,73]. The consumption of FLn by its reaction with the constituents of CSA led to the formation of extra C-S-H phases which were precipitated in the pore system of cement pastes. This in turn had improved and supported the physical, chemical and mechanical properties. This was contributed to the improvements of the densification parameters and the microstructure due to the reduction of voids, porosity, and water permeability [32,45,46,72]. The FLn or portlandite of cement pastes incorporated CSA › 30 wt. % (C7) continued to decrease due to that the high content of CSA at the expense of the OPC hindered its hydration, i.e. the hydration process was completely ceased.

Fig.8- Free lime contents of OPC pastes mixed with CSA hydrated till 90 days.

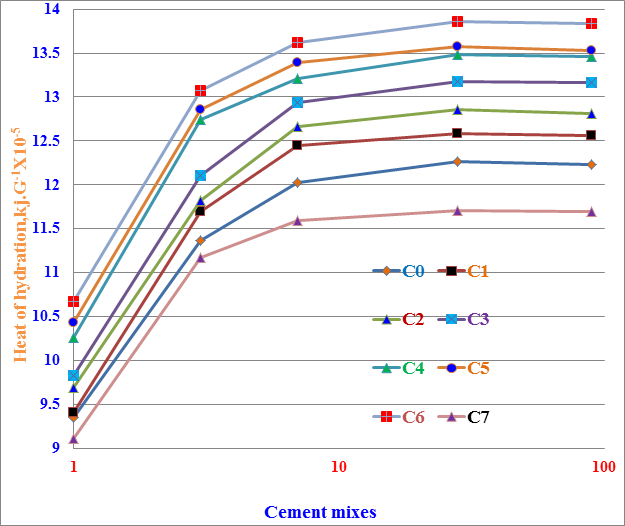

Figure 9 shows the heat of hydration (HH) of OPC pastes (C0) blended with different ratios of CSA (C1-C7) hydrated till 90 days. When water was poured on cement powder, heat due to hydration starts to generate at once. HH of cement pastes was generally increased with the hydration age till 28 days, but at later ages it was so slightly that it seemed to be constant. The same behavior was done by all cement pastes incorporated different ratios of CSA [75-78]. This is principally contributed to increasing the rate of hydration of cement phases that was coming from the pozzolanic reactions of CSA. This was accompanied by a gradual generation of heat [79-81]. Moreover, the rate of the produced HH was largely increased at early stages from 3 to 7 days. It is due to the initiation action on the hydration mechanism of C3S by the finer particles of CSA. During older periods (28-90 days), the rate of hydration and the released HH increased so little that it seemed to be unchanged or stable. This may be due to the non-activation action of C3S and the slight activation action mechanism of β-C2S at later ages. Also, the HH enhanced little as the CSA addition enhanced, but only till 30 % (C6). The increased values of HH are mainly attributed to two hydration mechanisms. The first is the hydration of cement phases and the second is the pozzolanic reactions of CSA with the evolving or formed free lime from the first process [75,76,79,80]. The HH was then unchanged with any further increase of CSA addition (C7). It is principally due to the dilution action of CSA on the cementitious compounds and the high SiO2 content of CSA. So, the high CSA content must be avoid due to its adverse action [77-81].

Fig. 9-Heat of hydration of OPC pastes mixed with CSA hydrated till 90 days.

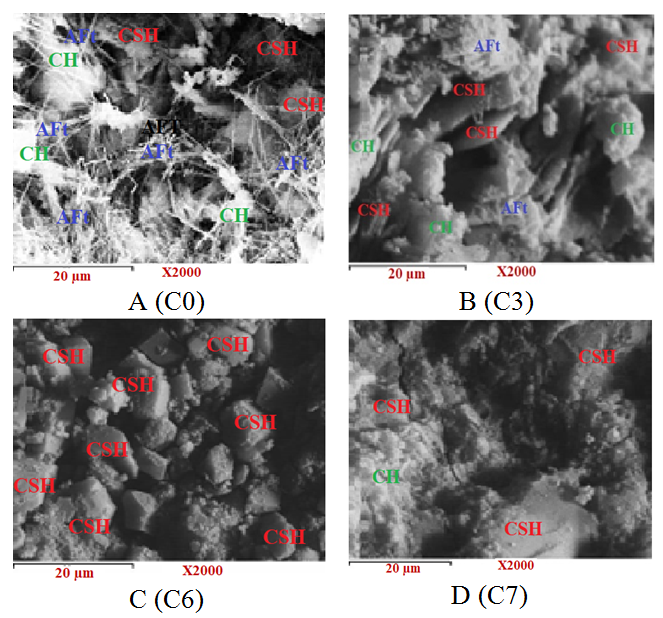

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) of OPC pastes blended with different ratios of CSA (A, B, C and D) or C0, C3, C6 and C7) hydrated till 90 days is demonstrated in Figure 10. In image A of the blank (C0), ettringite phase was clearly shown as needle-like crystals and also pits of free lime covered the surfaces of CSSA particles that were resulted from the normal hydration process. Also, crystals of CSH were formed. In image B (C3), the crystals of CSH and piles of free Ca (OH)2 were increased, but the ettringite phase was clearly decreased. In image C (C6), it was full of CSH and no pits of free lime, while the ettringite phase was completely disappeared. In the image D (C7), there are some internal cracks were noted and the reappearance of a very small amount of free lime which negatively reflected on the physical and mechanical properties. Moreover, the porosity was gradually decreased till C6 with the lowest degree of porosity. So, the cement batch (C6) could be considered the optimum one with well-developed crystal growth.

Fig. 10-SEM micrographs of OPC pastes (C0), C3, C6 and C7.

Conclusions

The pozzolanic performance and characteristics of the nanograin sized particles CSA were assessed. The CSA needs more water to form good cement pastes, i.e. the w/c- ratio continuously increased causes. Also, it causes a gradual retardation in both initial and final setting times, i.e. as CSA addition enhanced, the retardation time increased too. The resulting free lime in the cement paste with 0% CSA (C0) on 90 days was approximately 9.05%. This result significantly decreased with increasing of both curing time and CSA content. So, CSA is a pozzolanic material. As it is clear, the added CSA › 30 wt% (C7), the CH content starts to increase. It is principally contributed to the stopping or finishing of pozzolanic activity of the added material. The physical properties of cement pastes contained CSA material were improved and enhanced with curing time and CSA content, but only up to 30 wt%. Flexural and compressive strengths of the blended cement improved and enhanced with the increase of CSA content till 30 % (C6). Any further increase of CSA content › 30 wt. %, the physical and mechanical properties would be diminished. So, the optimum CSA addition to cement without adverse effects on its characteristics is 30 wt. %. SEM spectra revealed a higher quantity of CSHs in CSA paste forming a denser and more compact microstructure. Adding a large quantity of CSA caused the reduction of the heat of hydration and prolonged the time required to reach the silicate and aluminate reaction. This has led to a delay in hydration and resulted in excess setting times and reduced early and late strength development. The CSA powder contains SiO2 and Al2O3 › 90% of its total mass, and therefore it has a natural of pozzolanic materials. Blending CSA with OPC could be enhanced the pozzolanic performance forming additional CSH-gel because it improves the densification parameters of the OPC pastes, i.e. it reduced the voids, porosity, and water permeability.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by National Research Centre, Cairo, Egypt.

Declaration of competing interest

The author declares that there are no financial or competing conflicts of interest in this work.

Funding

The research article is self-sponsored.

References

[1] Y. Geng, Z. Wang, L. Shen, and J. Zhao (2019) Calculating of CO2 emission factors for Chinese cement production based on inorganic carbon and organic carbon,” Journal of Cleaner Production, 217, 503-509.

[2] L. Wang, L. Chen, J. L. Provis, D. C. W. Tsang, and C. S. Poon (2020) Accelerated carbonation of reactive MgO and Portland cement blends under flowing CO2 gas, Cement and Concrete Composites, 106, Journal Pre-proof 27 468.

[3] D. Coffetti, E. Crotti, G. Gazzaniga, M. Carrara, T. Pastore, and L. Coppola (2022) Pathways towards sustainable concrete, Cem. Conc. Res., 154.

[4] M. Shahbaz, D. Balsalobre-Lorente, and A. Sinha (2019) Foreign direct Investment–CO2 emissions nexus in Middle East and North African countries: Importance of biomass energy consumption, Journal of Cleaner Production, 217, 603-614.

[5] K.-H. Yang, Y.-B. Jung, M.-S. Cho, and S.-H. Tae (2015) Effect of supplementary cementitious materials on reduction of CO2 emissions from concrete, Journal of Cleaner Production, 103, 774-783.

[6] M. C. G. Juenger, and R. Siddique (2015) Recent advances in understanding the role of supplementary cementitious materials in concrete, Cement and Concrete Research, 78, 71-80.

[7] T. A. Fode, Y. A. Chande Jande, and T. Kivevele (2023) Effects of different supplementary cementitious materials on durability and mechanical properties of cement composite – Comprehensive review, Heliyon, 9, 7, e17924.

[8] C. Shi, B. Qu, and J. L. Provis (2019) Recent progress in low-carbon binders, Cement and Concrete Research, 122, 227-250.

[9] M. Cheng, L. Wu, Y. Huang, Y. Luo, and P. Christie (2014) Total concentrations of heavy metals and occurrence of antibiotics in sewage sludges from cities throughout China,” Journal of Soils and Sediments, 14, 6, 1123-1135.

[10] X. Lishan, L. Tao, W. Yin, Y. Zhilong, and L. Jiangfu (2018) Comparative life cycle assessment of sludge management: A case study of Xiamen, China, Journal of Cleaner Production, 192, 354- 489.

[11] J. Zhang, W. Niu, Y. Yang, D. Hou, and B. Dong (2022) Machine learning prediction models for compressive strength of calcined sludge-cement composites, Construction and Building Materials, 346.

[12] Y. Yang, H. Wang, Z. Li, M. Sun, and J. Zhang (2024) Research on mechanical and durability properties of sintered sludge cement, Developments in the Built Environment, 18, 100395, 2024/04/01/.

[13] HHM Darweesh (2018), Nanomaterials, classification and properties, Part I, Nanoscience,Vol. 1, 4-11. www.itspoa.com/journal/nano.

[14] A. Jamshidi, M. Jamshidi, N. Mehrdadi, A. Shasavandi, and F. Pacheco-Torgal (2012) Mechanical Performance of Concrete with Partial Replacement of Sand by Sewage Sludge Ash from Incineration, Materials Science Forum, vol. 730-732, 462-467.

[15] C. S. Karadumpa, and R. K. Pancharathi (2021) Influence of Particle Packing Theories on Strength and Microstructure Properties of Composite Cement–Based Mortars, Journal of Materials in Civil Engineering, 33, 10.

[16] C. J. Lynn, R. K. Dhir, G. S. Ghataora, and R. P. West (2015) Sewage sludge ash characteristics and potential for use in concrete, Construction and Building Materials, 98, 767-779.

[17] A. Tipraj, and T. Shanmugapriya (2022) A comprehensive analysis on optimization of Sewage sludge ash as a binding material for a sustainable construction practice: A state of the art review, Materials Today: Proceedings, 64, 1094-1101.

[18] L. Wang, F. Zou, X. Fang, D. C. W. Tsang, C. S. Poon, Z. Leng, and K. Baek (2018) A novel type of controlled low strength material derived from alum sludge and green materials, Construction and Building Materials, 165, 792-800.

[19] S.-C. Pan, D.-H. Tseng, C.-C. Lee, and C. Lee (2003) Influence of the fineness of sewage sludge ash on the mortar properties, Cement and Concrete Research, 33, 11, 1749-1754.

[20] Z. Chen, and C. S. Poon (2017) Comparative studies on the effects of sewage sludge ash and fly ash on cement hydration and properties of cement mortars, Construction and Building Materials, 154, 791-803.

[21] S. Vilakazi, E. Onyari, O. Nkwonta, and J. K. Bwapwa (2023) Reuse of domestic sewage sludge to achieve a zero waste strategy & improve concrete strength & durability – A review, South African Journal of Chemical Engineering, 43, 122-127.

[22] G. M. Rabie, H. A. El-Halim, and E. H. Rozaik (2019) Influence of using dry and wet wastewater sludge in concrete mix on its physical and mechanical properties, Ain Shams Engineering Journal, vol. 10, 4, 705-712.

[23] C. Gu, Y. Ji, Y. Zhang, Y. Yang, J. Liu, and T. Ni (2021) Recycling use of sulfate-rich sewage sludge ash (SR-SSA) in cement-based materials: Assessment on the basic properties, volume deformation and microstructure of SR-SSA blended cement pastes, Journal of Cleaner Production, 282.

[24] M. Cyr, M. Coutand, and P. Clastres (2007) Technological and environmental behavior of sewage sludge ash (SSA) in cement-based materials, Cement and Concrete Research, 37, 8, 1278-1289.

[25] P. de Azevedo Basto, H. Savastano Junior, and A. A. de Melo Neto (2019) Characterization and pozzolanic properties of sewage sludge ashes (SSA) by electrical conductivity, Cement and Concrete Composites, 104.

[26] P. Suraneni, and J. Weiss (2017) Examining the pozzolanicity of supplementary cementitious 542 materials using isothermal calorimetry and thermogravimetric analysis, Cement and Concrete Composites, 83, 273-278.

[27] M. Mejdi, M. Saillio, T. Chaussadent, L. Divet, and A. Tagnit-Hamou (2020) Hydration mechanisms of sewage sludge ashes used as cement replacement, Cement and Concrete Research, 135.

[28] K. L. Lin, K. Y. Chiang, and C. Y. Lin (2005) Hydration characteristics of waste sludge ash that is reused in eco-cement clinkers, Cement and Concrete Research, 35, 6, 1074-1081, 29 554.

[29] B. Krejcirikova, L. M. Ottosen, G. M. Kirkelund, C. Rode, and R. Peuhkuri (2019) Characterization of sewage sludge ash and its effect on moisture physics of mortar, Journal of Building Engineering, 21, 396-403.

[30] A. Bialowiec, W. Janczukowicz, and M. Krzemieniewski (2009) Possibilities of management of waste fly ashes from sewage sludge thermal treatment in the aspect of legal regulations, Rocznik Ochrona Srodowiska, 11, 959-971.

[31] P. Suraneni, A. Hajibabaee, S. Ramanathan, Y. Wang, and J. Weiss (2019) New insights from reactivity testing of supplementary cementitious materials, Cement and Concrete Composites, 103, 331-338

[32] H.H.M. Darweesh and H. Abu-El-Naga (2024) The Performance of Portland Cement Pastes (OPC) Incorporated with Ceramic Sanitary Ware Powder Waste (CSPW) at Ambient Temperature, Sustainable Materials Processing and Management, 4, 1, 56-70. https://publisher.uthm.edu.my/ojs/index.php/jsmpm.

[33] H.H.M. Darweesh and H. Abu-El-Naga (2024) Effect of curing temperatures on the hydration of cement pastes containing nanograin size particles of sanitary ware ceramic powder waste, International Journal of Materials Science, 5, 1 07-14. https://www.mechanicaljournals.com/materials-science.

[34] S. Naamane, Z. Rais, and M. Taleb (2016) The effectiveness of the incineration of sewage sludge on the evolution of physicochemical and mechanical properties of Portland cement, Construction and Building Materials, 112, 783-789.

[35] L. M. Ottosen, D. Thornberg, Y. Cohen, and S. Stiernström (2022) Utilization of acid-washed sewage sludge ash as sand or cement replacement in concrete, Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 176.

[36] K. Motisariya, G. Agrawal, M. Baria, V. Srivastava, and D. N. Dave (2023) Experimental analysis of strength and durability properties of cement binders and mortars with addition of microfine sewage sludge ash (SSA) particles, Materials Today: Proceedings, 85, 24-28.

[37] P. C. Hewlett and M. Liska (2019), Pozzolanas and pozzolanic materials, in: Lea’s chemistry of cement and concrete (5th ed.), Butterworth-Heinemann, 363-467.

[38] ASTM C187 (1998) Test method for amount of water required for normal consistency of hydraulic cement paste. American Society for Testing and Materials.. https://doi.org/10.1520/c0187-98.

[39] ASTM C191-21 (1998) Standard test methods for time of setting of Hydraulic cement by Vicat Needle. West Conshohocken, PA, USA: ASTM International; c2021. p. 8-10. https://doi.org/10.1520/c0191-01.

[40] ASTM C642-21 (2021) Standard test method for density, absorption, and voids in hardened concrete. West Conshohocken, PA, USA: ASTM International, p. 3.

[41] H.H.M. Darweesh (2020) Specific characteristics and microstructure of Portland cement pastes containing wheat straw ash (WSA). Indian Journal of Engineering;17(48):569-583.

[42] ASTM C293-02 (2002) Standard test method for flexural strength of concrete (using simple beam with centerpoint loading). American Society for Testing and Materials. https://doi.org/10.1520/c0293-02

[43] ASTM C348-21 (2021) Standard Test Method for Flexural Strength of Hydraulic-Cement Mortars, ASTM International, West Conshohocken, PA,.

[44] ASTM C109-20 (2020) Standard Test Method for Compressive Strength of Hydraulic Cement Mortars. ASTM International, West Conshohocken, PA; c2020. https://doi.org/10.1520/c0109_c0109m-07 527.

[45] H.H.M. Darweesh (2024) Performance of brick demolition waste in Geopolymer cement pastes, International Journal of Civil Engineering and Architecture Engineering; 5(1): 34-44. https://www.civilengineeringjournals.com/ijceae.

[46] H.H.M. Darweesh (2024) Reactive magnesia Portland blended cement pastes, Journal of Civil Engineering and Applications 2024; 5(1): 23-32. http://www.civilengineeringjournals.com/jcea.

[47] H.H.M. Darweesh (2023) Utilization of Oyster Shell Powder for Hydration and Mechanical Properties Improvement of Portland Cement Pastes, JOURNAL OF SUSTAINABLE MATERIALS PROCESSING AND MANAGEMENT, 3, 1, 19-30. http://publisher.uthm.edu.my/ojs/index.php/jsmpm.

[48] H.H.M. Darweesh (2020) Characteristics of Portland cement Pastes Blended with Silica Nanoparticles, To Chemistry; 5:1- 14. http://purkh.com/index.php/tochem.

[49] H.H.M. Darweesh (2020) Physico-mechanical properties and microstructure of Portland cement pastes replaced by corn stalk ash (CSA), International Journal of Chemical Research and Development, Volume 2; Issue 1; 24-33. www.chemicaljournal.in.

[50] ASTM- Standards C186-80, (1980) Standard Test Method for Heat of Hydration of Hydraulic Cement.

[51] M. Elmaghraby, H.S. Mekky and M.A. Serry, Light weight insulating concrete based on natural pumice aggregate, InterCeram: International Ceramic Review, 61(2012) 354-357.

[52] T. D. Garrett, H.E. Cardenas, J.G. Lynam, Sugarcane bagasse and rice husk ash pozzolans: Cement strength and corrosion effects when using saltwater, Current Research in Green and Sustainable Chemistry 1-2(2020) 7-13.

[53] H. H. M. Darweesh (2021) Physical and Chemo/Mechanical behaviors of fly ash and silica

fume belite cement pastes- Part I, NanoNEXT, 2, 2, 1-15. https://doi.org/10.34256/nnxt2121.

[54] D. Coffetti, E. Crotti , G. Gazzaniga, M. Carrara, T. Pastore, L. Coppola (2022) Pathways towards sustainable concrete. Cement Concr Res; 154:106718. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconres.2022.106718.

[55] J. Wang; Z. Che; K. Zhang; Y. Fan; D. Niu and X. Guan (2023) Performance of recycled aggregate concrete with supplementary cementitious materials (fly ash, GBFS, silica fume, and metakaolin): mechanical properties, pore structure, and water absorption. Constr. Build. Mater. 368, 130455.

[56] R. S. Fakhri and E. T. Dawood (2023) Influence of binary blended cement containing slag and limestone powder to produce sustainable mortar. AIP Conf Proc,; 2862(1): 020028. https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0171499.

[57] A. Sagade and M. Fall (2024) Study of fresh properties of cemented paste backfill material with ternary cement blends. Construct Build Mater, 411:134287. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2023.134287.

[58] O. Mahmoodi, H. Siad, M. Lachemi, S. Dadsetan and M. Sahmaran (2020) Development of ceramic tile waste geopolymer binders based on pre-targeted chemical ratios and ambient curing. Construction and Building Materials; 258: 120297. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2020.120297.

[59] H. Wu, J. Gao, C. Liu, Y. Zhao and S. Li (2024) Development of nano-silica modification to enhance the micro-macro properties of cement-based materials with recycled clay brick powder. Journal of Building Engineering; 86: 108854. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2024.108854.

[60] A. O. Tanash, K. Muthusamy, Y. F. Mat and M. A. Ismail (2023) Potential of recycled powder from clay brick, sanitary ware, and concrete waste as a cement substitute for concrete: An overview. Construction and Building Materials; 401: 132760. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2023.132760.

[61] B. Tian, W. Ma, X. Li, D. Jiang, C. Zhang, J. Xu J, et al. (2023) Effect of ceramic polishing waste on the properties of alkali-activated slag pastes: Shrinkage, hydration and mechanical property. Journal of Building Engineering. 63:105448. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2022.105448.

[62] G. Chen, S. Li, Y. Zhao, Z. Xu, X. Luo, J. Gao, et al. (2023) Hydration and microstructure evolution of a novel lowcarbon concrete containing recycled clay brick powder and ground granulated blast furnace slag. Construction and Building Materials, 386:131596. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2023.131596.

[63] L. Likes, A. Markandeya, M. M. Haider, D. Bollinger, J. S. McCloy, S. Nassiri, et al. (2022) Recycled concrete and brick powders as supplements to Portland cement for more sustainable concrete. Journal of Cleaner Production, 364:132651. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.132651.

[64] S. Li, G. Chen, Y. Zhao, Z. Xu, X. Luo, C. Liu, et al. (2023) Investigation on the reactivity of recycled brick powder. International Journal of Civil Engineering and Architecture Engineering https://www.civilengineeringjournals.com/ijceae ~ 44 ~ Cement and Concrete Composites, 139: 105042. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2023.105042.

[65] P. Jain, R. Gupta and S. Chaudhary (2022) Comprehensive assessment of ceramic ETP sludge waste as a SCM for the production of concrete. Journal of Building Engineering, 57:104973. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2022.104973.2.

[66] S. Al-Shmaisani, R. D. Kalina, R. D. Ferron and M. C. G.Juenger (2022) Critical assessment of rapid methods to qualify supplementary cementitious materials for use in concrete, Cem. Concr. Res. 153, 106709, https://doi.org/10.1016/j. cemconres.2021.106709.

[67] B. Tian, W. Ma, X. Li, D. Jiang, C. Zhang, J. Xu, et al. (2023) Effect of ceramic polishing waste on the properties of alkali-activated slag pastes: Shrinkage, hydration and mechanical property. Journal of Building Engineering. 63:105448. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2022.105448.

[68] P. Jain, R. Gupta and S. Chaudhary (2022) Comprehensive assessment of ceramic ETP sludge waste as a SCM for the production of concrete. Journal of Building Engineering, 57:104973. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2022.104973.2.

[69] H.H.M. Darweesh (2016) Ceramic Wall and Floor Tiles Containing Local Waste of Cement Kiln Dust- Part II: Dry and Firing Shrinkage as well as Mechanical Properties, American Journal of Civil Engineering and Architecture, Vol. 4, No. 2, 44-49. DOI:10.12691/ajcea-4-2-1.

[70] Y. Zhang and O. Çopuroglu˘ (2024) Correlation between slag reactivity and cement paste properties: the influence of slag chemistry. J Mater Civ Eng, , 36(3):04023618. https://doi.org/10.1061/JMCEE7.MTENG-16385.

[71] A. R. G. Azevedo, T. M. Marvila, W. Júnior Fernandes, J. Alexandre, G. C. Xavier, E. B. Zanelato, N. A. Cerqueira, L. G. Pedroti and B. C. Mendes. Assessing the potential of sludge generated by the pulp and paper industry in assembling locking blocks. J Build Eng, 2019, 23:334–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2019.02.012.

[72] Y. Zhang and O. Çopuroglu˘, 2024Correlation between slag reactivity and cement paste properties: the influence of slag chemistry. J Mater Civ Eng, , 36(3):04023618. https://doi.org/10.1061/JMCEE7.MTENG-16385.

[73] A. R. G. Azevedo, T. M. Marvila, W. Júnior Fernandes, J. Alexandre, G. C. Xavier, E. B. Zanelato, N. A. Cerqueira, L. G. Pedroti and B. C. Mendes BC (2019) Assessing the potential of sludge generated by the pulp and paper industry in assembling locking blocks. J Build Eng,, 23:334–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2019.02.012.

[74] P. Jain, R. Gupta and S. Chaudhary (2022) Comprehensive assessment of ceramic ETP sludge waste as a SCM for the production of concrete. Journal of Building Engineering, 57:104973. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2022.104973.2.

[75] A. S. El-Dieb and D. M. Kanaan (2018) Ceramic waste powder an alternative cement replacement – characterization and evaluation. Sustainable Materials and Technologies; 17:e00063. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.susmat.2018.e00063.

[76] A. Azevedo, P. de Matos, M. Marvila, R. Sakata, L. Silvestro, P. Gleize, J. D. Brito (2021), Rheology, Hydration, and microstructure of Portland cement pastes produced with ground Açaí fibers. Applied Sciences;. https://doi.org/10.3390/app11073036.

[77] H.H.M. Darweesh; M. A. El-Suoud (2019) Influence of Sugarcane Bagasse Ash Substitution on Portland cement Characteristics. Indian J. Eng., 16, 252-266.

[78] H.H.M. Darweesh; El-Suoud MA (2020) Palm Ash as a Pozzolanic Material for Portland cement Pastes.To Chemistry Journal, 4, 72-85.

[79] L. R. Steiner, A. M. Bernardin and F. Pelisser (2015), Effectiveness of ceramic tile polishing residues as supplementary cementitious materials for cement mortars. Sustainable Materials and Technologies; 4:30–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.susmat.2015.05.001.

[80] H.H.M. Darweesh (2020) Influence of Sun Flower Stalk Ash (SFSA) on the Behavior of Portland cement Pastes. Results in Engineering, 100171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rineng.2020.100171.

[81] H.H.M. Darweesh (2021) Low Heat Blended Cements Containing Nanosized Particles of Natural Pumice Alone or in Combination with Granulated Blast Furnace Slag, Nano Prog., 3(5), 38-46. DOI:10.36686/Ariviyal.NP.2021.03.05.025.