Introduction: Microorganisms are capable of breaking down organic pollutants in natural water and soil environments through cometabolism (Prakash and Karthikeyan, 2013). Wastewater from the silk industry is a major source of aesthetic pollution, as the dyes it contains can contaminate soil. The salts and heavy metals present in this effluent are toxic to aquatic life, and certain dyes are carcinogenic, posing serious health risks (Alinsafi et al., 2005). Bacterial degradation of dyes often begins under static or anaerobic conditions via enzymatic transformation reactions (Carvalho et al., 2008).

Biodegradation refers to the biologically mediated breakdown of chemical compounds. When this process is complete, it results in mineralization—the total decomposition of organic molecules into water, carbon dioxide, and other inorganic end products. Such processes can convert dyes into harmless inorganic compounds like carbon dioxide and water, generating only minimal, relatively insignificant amounts of sludge. The advantages of biological treatment or biodegradation include low cost, renewable and regenerative activity, and the absence of secondary hazards (Andleeb et al., 2010).

Soil pH, which indicates acidity or alkalinity, and soil electrical conductivity (EC), which reflects soil properties, are key factors affecting crop productivity. Effluent contamination can alter soil composition and structure, leading to changes in material behavior and soil texture over time (Ann et al., 2005).

Calcium and nitrogen absorbed from soil are essential for plant growth, providing structural support to cell walls and other cellular components. When plants experience physical or biochemical stress, these nutrient levels can change (Larry, 2011). Phosphorus and potassium play vital roles in growth and metabolism, including storage and transfer of energy, forming critical cell components, promoting root development and tillering, and ensuring proper maturation (Channakeshava et al., 2006).

Iron is a major mineral in soil but is often unavailable for direct uptake by plants or microorganisms (Ahamed, 2007). Copper is an essential micronutrient for plants, humans, and animals, contributing to key biological functions and serving as a component of amino acids and proteins. Zinc is another critical micronutrient for plants and animals. Its uptake by plants is common, but excess zinc is phototoxic and can reduce crop yield and degrade soil fertility (Linus and Erik, 2007). Contamination of soil with silk dyeing effluent can lead to losses of iron, copper, and zinc, further impacting soil health and productivity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

3.1 Collection of silk dyeing effluent: The silk dyeing effluent was collected from the effluent disposal site of small scale silk dyeing industry in airtight plastic containers, located at Seelanaickenpatti in Salem district.

3.2 Collection of Biofertilizers: The Biofertilizer Pseudomonas fluorescens was collected from the Tamil Nadu Agricultural University, Coimbatore.

3.3 Soil preparation for the study

The red soil and the sand were mixed at the ratio of 3:1. Each pot was filled with 7 kg of soil. In Phase 1 and Phase 3, five GLVs were grown with four replicates. In phase 2, three pots for each of the four different concentrations (25%, 50%, 75% and 100%) were used. The biofertilizer, Pseudomonas fluorescens was mixed at the rate of 5 tonnes ha-1 with crude effluent and used in Phase 3. The bacterial concentration of the biofertilizer was 108 Colony forming units (CFU ml-1).

3.4 Soil analysis

The soil which was treated with freshwater for the growth of the GLVs served as the control soil. The crude effluent soil treated with 100% of the crude silk dyeing effluent without dilution and the effluent biotreated soil is the soil treated with the biotreated effluent. The analysis of control soil, crude effluent soil and effluent biotreated soil samples in the initial stages of treatment was carried out.

The reference for methodology and the appendix number for the measurement of soil pH and electrical conductivity are given in Table 1.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The soil analysis indicated that the pH of the soil used in this study was within the optimal range and that the soil had a sandy loamy texture. Electrical conductivity was also within the optimal range, indicating salt-free conditions. However, the calcium and nitrogen contents were below the recommended optimal levels. The soil’s phosphorus content was approximately 10 kg/ha, which corresponds to the minimum level of phosphorus suggested by Antonio et al. (2013) in the general guidelines for crop nutrients and limestone recommendations from Iowa University. Potassium levels, on the other hand, were within the optimal range.

4.1 Physical analysis of the control, silk dying effluent contaminated soil and Biotreated soil

Table 1 depicts the levels of physical parameters in the control soil,silk dying effluent contaminated soil and Biotreated soil.

Table 1

Physical analysis of the control, silk dying effluent contaminated soil and Biotreated soil

| Parameter | Optimal range in Normal soil* | Control soil (C) | Effluent soil (E) | Biotreated effluent soil ( by Pseudomonas fluorescens ) (EB) |

| pH | 6-7.5 | 7.1 | 8.1 | 7.5 |

| EC | <1.0 | 0.1(Good condition) | 1.2 | 0.2 |

| Texture | – | S1 –Type sandy loam (Red soil: sand) (3:1) | S1- Type sandy clay loam (Red soil: sand) (3:1) with Dyeing effluent | S1- type sandy clay loam (Red soil: sand) (3:1) with effluent and biofertilizer (Pseudomonas fluorescens) |

* The optimal range in normal soil was taken from ‘Soil Test Interpretation Guide’, EC 1478, Oregon State University, 2011.

4.1.1 Analysis of the soil contaminated with silk dyeing effluent

Table 1 presents the analysis of physical parameters in silk dyeing effluent–treated soil. The pH (8.1) and electrical conductivity (EC, 1.2 dS/m) observed in the effluent-contaminated soil exceeded standard limits. Similar findings were reported by Nidhi and Ashwani (2011) in soil samples collected from the Sanganer region during August.

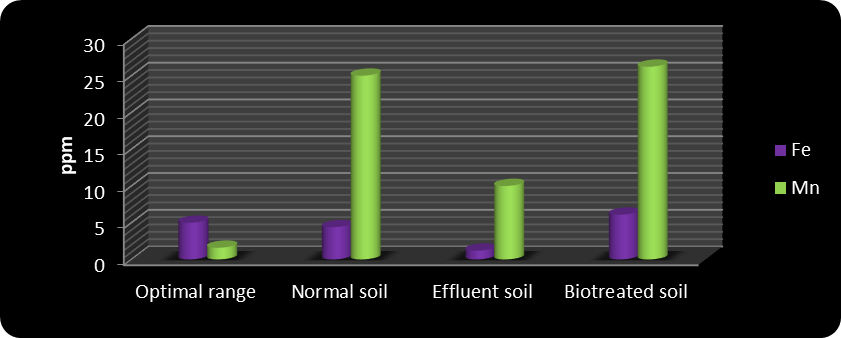

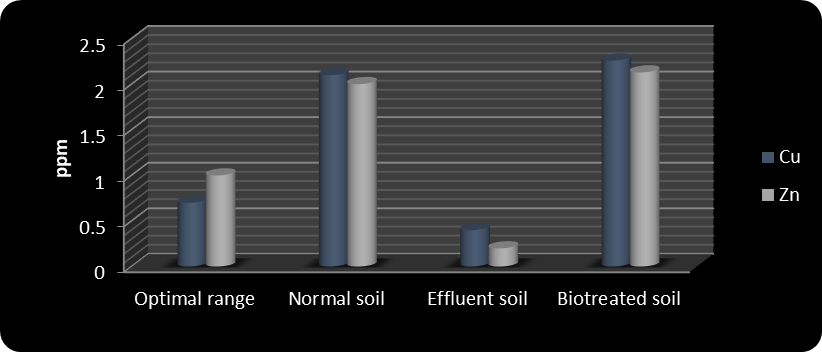

The soil texture was classified as sandy clay and loam (S1-type). All measured macronutrients (N, P, K, and Ca) and micronutrients (Fe, Cu, and Zn), except manganese, were below optimal levels in the effluent-treated soil. These results indicate that effluent contamination reduces both macro- and micronutrient availability. Calcium deficiency, caused by leaching in contaminated water, can result in symptoms such as death at the growing point, dark green foliage, weakened stems, and flower drop (Larry, 2011). Nitrogen deficiency negatively affects cellular metabolism, potentially leading to stunted growth, reduced chlorophyll content, and plant death (Raymond et al., 2004). Additionally, the alkaline pH of the effluent may contribute to low copper availability, as heavy metals tend to precipitate as salts and settle as sediments under high pH conditions (Rao and Manjula, 2000).

These findings suggest that effluent-treated soil is unable to supply sufficient macro- and micronutrients for the growth of green leafy vegetables (GLVs). Rena and Kanika (2013) similarly reported that industrial effluent adversely affects soil physico-chemical properties and fertility.

4.1.2 Physico-Chemical Analysis of Biotreated Effluent Soil

Biofertilizers, which contain living microorganisms, enhance soil nutrient quality. Nutrient availability for plants is regulated by rhizospheric microbial activity (Herrmann et al., 2005). Table 3 shows the macronutrient and micronutrient levels in soil treated with Pseudomonas fluorescens.

In biotreated soil, pH and EC remained within standard limits, similar to control soil. Soil texture also remained consistent throughout the study. Results indicated that biotreatment improved micronutrient levels to within optimal ranges. The application of biofertilizer increased macronutrient concentrations from 105, 76, 4, and 137 ppm in effluent-treated soil to 110, 200, 14.5, and 390 ppm in biotreated effluent soil for Ca, N, P, and K, respectively. Das et al. (2009) reported similar improvements in soil and plant N, P, and K levels following biofertilizer application. Micronutrients also increased: Fe, Mn, Cu, and Zn rose from 1.2, 10, 0.4, and 0.2 ppm in effluent-treated soil to 6.1, 26.22, 2.26, and 2.13 ppm in biotreated soil.

These results demonstrate that biofertilization effectively mitigates the negative impact of effluent on soil nutrients.

4.1.2.1 Effect of Fresh Water, Crude Effluent, and Biotreated Effluent on Soil Nutrients

Macronutrient and micronutrient levels under different treatments are shown in Figures 1–4. The data clearly indicate that biotreated effluent soil had higher levels of calcium, nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium, iron, manganese, copper, and zinc compared to effluent-contaminated soil.

Figure 1 Calcium in the soil of different treatments

Figure 2 Nitrogen, phosphorus and potassium in the soil of different treatments

Figure 3 Iron and manganese in the soil of different treatments

Figure 4 Copper and zinc in the soil of different treatments

Conclusion

The present study demonstrated that biotreatment enhanced the macro- and micronutrient content of effluent-contaminated soil, making it a cost-effective and eco-friendly approach to sustaining the productivity of green leafy vegetable (GLV) crops.

In this study, the iron content was measured at 4.4, slightly below the optimal range, while other micronutrients—manganese, copper, and zinc—were within their optimal concentrations.

Overall, the experimental soil used for cultivating the selected GLVs was rich in macro- and micronutrients, providing a supportive environment for plant growth. Fertile soil with a balanced composition of macro- and micronutrients is capable of meeting the complete dietary requirements of developing plants.

REFERENCES

Ahamed, I.H. (2007), Efficacy of rhizobacteria for growth promotion and biocontrol of Pythium ultimum and Fusarium oxysporum on sorghum in Ethiopia and South Africa, Ph.D Thesis, Department of Microbiology and Plant Pathology, University of Pretoria, 6.

Alinsafi, A., Khemis, M., Pons, M.N., Leclerc, J.P., Yaacoubi, A., Benthammou, A. and Nejmeddine, A. (2005), Electro-coagulation of reactive textile dyes and textile wastewater, Chemical Engineering and Processing, Process Intensification, 44: 461-470.

Andleeb, S., Atiq, N., Ali, M.I., Hussain, R.R., Shafique, M., Ahmad, B., Ghumro, P.B., Hussain, M., Hameed, A. and Ahmad, S. (2010), Biological treatment of textile effluent in stirred tank bioreactor, International Journal of Agricultural Biology, 12: 256-260.

Antonio, P.M., John, E.S. and Stephen, K.B. (2013), General guide for crop nutrient and

limestone, Department of Agronomy, Lowa State UniversityExtension and Outreach, 1-14.

Ann, M., Clain, J. and Jeff, J. (2005), Basic soil properties, Soil and water management module I, 1-12.

Das, P., Choudhari, A.R., Dhawan, A. and Singh, R. (2009), Role of ascorbic acid in Human seminal plasma against the oxidative damage to the sperms, Indian Journal of Clinical Biochemistry, 24: 312-315.

Carvalho, M.C., Pereira, C., Goncalves, I.C., Pinheiro, H.M., Santos, A.R., Lopes, A. and Ferra, M.I. (2008), Assessment of the biodegradability of a monosulfonated azo dye and aromatic amines, International Biodeterioration and Biodegradation, 62: 96-103.

Channakeshava, S., Sarangamath P.A. and Anand, N. (2006), Effect of different phosphate sources on leaching and re-distribution of fluorine in submerged acid soils of utter Kannada, Journal of Ecotoxicology and Environmental Monitoring, 16: 437-442.

Herrmann, A., Witter, E. and Katterer, T. (2005), A method to assess whether ‘preferential use’ occurs after 15N ammonium addition; implication for the 15N isotope dilution technique, Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 37: 183-186.

Larry, O. (2011), Secondary Plant Nutrients: Calcium, Magnesium, and Sulfur, Mississippi State University, 1-4.

Linus, H. and Erik, L. (2007), Soil and plant contamination by textile industries at ZFILM, Managua Project work in Aquatic and Environmental Engineering, 10 ECTS, Uppsala University,1-65.

Nidhi, J. and Ashwani, K. (2011), Physio-chemical Analysis of Industrial effluents of Sanganer region of Jaipur Rajasthan, Research Journal of Agricultural Science, 2: 354-356.

Prakash, P. and Karthikeyan, B. (2013),Isolation and purification of Plant Growth Promoting Rhizobacteria (PGPR) from the rhizosphere of Acorus Calamus grown soil, Indian Streams Research Journal, 3: 1-13.

Rao, L.M. and Manjula, S.P.R. (2000), Heavy metal accumulation in the cat fish Mystus vittatus (Bloch) from Mehadrigedda stream of Visakhapatnam, India, Pollution Research, 19: 325-329.

Raymond, J., Siefert, J.L., Staples, C.R. and Blankenship, R.E. (2004), The Natural history of nitrogen fixation, Molecular Biology and Evolution, 21: 541-554.