Introduction: Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) are ubiquitous environmental pollutants, primarily generated during the incomplete combustion of organic materials such as coal, oil, petrol, and wood. These compounds are mostly colorless, white, or pale yellow solids [1]. PAHs can be categorized into two groups: low molecular weight PAHs, containing fewer than four aromatic rings (e.g., naphthalene, acenaphthene, fluorene, phenanthrene, and anthracene), and high molecular weight PAHs, with four or more rings (e.g., pyrene, chrysene, benzo(a)pyrene, benzo(a)anthracene, indeno(1,2,3-cd)pyrene, benzo(k)fluoranthene). The chemical stability, low solubility, and high sorption capacity of high molecular weight PAHs contribute significantly to their environmental persistence [2].

Major industries that rely on fossil fuels in the production of goods or energy generate PAHs, with higher concentrations typically found near heavy industries. Natural sources of PAHs include forest fires, volcanic eruptions, and decaying organic matter [3]. PAHs are introduced into the environment primarily through pyrogenic, petrogenic, and biological pathways [1]. Pyrogenic PAHs form when organic substances are exposed to high temperatures (350–1200 °C) under low or no oxygen conditions [4]. Petrogenic PAHs are generated during crude oil maturation and similar processes, while biological PAHs are synthesized by certain plants or formed during the degradation of vegetative matter [5].

The occurrence of PAHs in foods and the environment is influenced by their physicochemical properties, including relative solubility in water and organic solvents [6]. Their lipophilic nature and low aqueous solubility [7] make soils the primary environmental sink, as PAHs readily adsorb to organic matter and are resistant to degradation [8,9]. Due to their persistence and hydrophobicity, PAHs accumulate in the soil matrix [10]. Certain PAHs are considered environmentally hazardous because of their toxic nature and tendency to bioaccumulate in humans [8].

PAHs are associated with mutagenic, carcinogenic, and persistent effects, raising global concerns about their impact on human health and the environment [11]. Experimental studies have shown embryotoxic effects of PAHs such as benzo(a)anthracene, benzo(a)pyrene, and naphthalene in animals [1]. Laboratory studies in mice indicated that maternal exposure to high levels of benzo(a)pyrene can lead to birth defects and reduced offspring body weight [12]. Exposure to PAHs during pregnancy has also been linked to adverse outcomes, including low birth weight, premature delivery, congenital heart defects, reduced IQ at age three, childhood asthma, and DNA damage [12].

Several studies have investigated soil PAH pollution and associated health risks near petrol stations in Nigeria and globally [13,14]. However, data on PAH levels in soils around fuel stations in Nibo, a fast-developing semi-urban area in Awka South Local Government Area of Anambra State, is lacking. Such assessments are crucial in agrarian communities like Nibo, where the rapid development of fuel stations may expose residents to PAHs. Baseline environmental data would provide valuable insight into potential risks and inform public health interventions in Anambra State, South-Eastern Nigeria.

Materials and Methods

Sample Collection

Five soil samples each were collected from three locations labeled P1, P2, and Control. P1 and P2 represented soils from fuel stations located near intensive farming and residential areas, while the control samples were obtained from areas far from economic activities, including fuel stations. Soil samples were collected at a depth of 0–20 cm using a stainless-steel handheld auger, wrapped in labeled aluminum foil, and transported to the laboratory for analysis.

Preparation and Analysis

Soil samples were prepared according to the procedure described by [15]. Samples were sieved, oven-dried, and 10 g portions were extracted for 72 h using 100 mL of a hexane-acetone mixture (1:1) in a Soxhlet apparatus. The extract was decanted into a clean, dried round-bottom flask and concentrated to 5 mL using a rotary evaporator. The extract was fractionated on a silica gel column to isolate the aromatic portion using dichloromethane. This fraction was again concentrated to 5 mL and transferred to gas chromatography (GC) vials for analysis. Levels of anthracene, acenaphthene, phenanthrene, chrysene, pyrene, benzo(a)anthracene, and fluoranthene were determined using a GC 6890 Series.

Recovery tests for PAHs were performed in triplicate, yielding mean recoveries of 82–97%, which is considered acceptable [16].

Statistical Analysis

Data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation and analyzed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) at a 5% confidence level with IBM SPSS version 22.0.

Results and Discussion

Mean levels of the investigated PAHs in soils situated around fuel stations in Nibo, Awka South L.G.A., Anambra State.

| Sample site | Soil Depth (cm) | Mean levels of the PAHs (mg/kg) | Ftest p value | ||||||

| Anthracen e | Acenapthene | Phenanthrene | Chrysen e | Pyrene | Benzo( a)anthr acene | Flouran thene | |||

| P1 | 0-20 | 0.18 + 0.06 | – | 0.11 + 0.02 | 0.27 + 0.03 | 0.40 + 0.17 | 0.20 + 0.06 | – | 0.02 |

| P2 | 0-20 | 0.49 + 0.06 | 0.16 + 0.01 | 0.22 + 0.04 | 0.02+ 0.01 | 0.27 + 0.06 | 0.39 + 0.05 | – | 0.01 |

| Control | 0-20 | – | – | 0.04 + 0.02 | 0.02 + 0.01 | 0.07 + 0.02 | 0.06 + 0.01 | – | 0.02 |

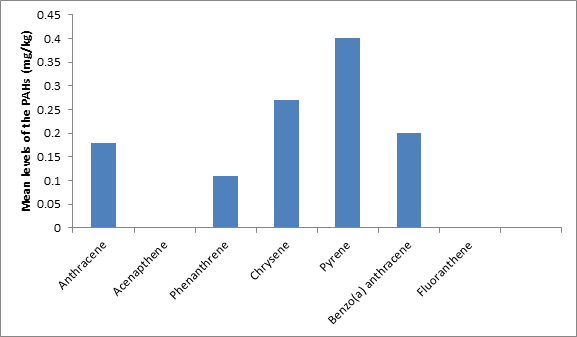

Result of Table shows that at soil depth 0-20cm of soil samples P1, the mean levels of anthracene , phenanthrene , chrysene , pyrene , benzo(a) anthracene and fluoranthene were 0.18±0.06, 0.11±0.02, 0.27±0.03, 0.40±0.17 and 0.20±0.06 mg/kg respectively. The mean levels of the investigated PAHs decreased in the soil samples P1 in the following order; pyrene> chrysene> benzo(a) anthracene > anthracene > phenanthrene as shown in Figure 1.

Fig 1 : Bar chart representation of the mean levels of the PAHs in the soil samples at P1 situated around fuel stations in Nibo,Awka South L.G.A., Anambra State.

This result therefore indicates that there was a higher contamination of the soils at P1 with the investigated high molecular weight PAHs than the low molecular weight PAHs. This observation is therefore a worrisome development considering the toxicities associated with exposure to high molecular weight PAHs. However, the mean levels of the investigated PAHs in the soil samples at P1 were within the recommended permissible of 1.5mg/kg set by [17, 18]. The mean levels of the PAHs at soil samples P1 were statistically significant

From the result of Table 1, the mean levels of anthracene , phenanthrene, chrysene, pyrene and benzo(a) anthracene in the soil samples at P2 were 0.49±0.06, 0.16±0.01 , 0.22±0.04, 0.02±0.01, 0.27±0.06 and 0.39±0.05mg/kg respectively. The order of decrease of the PAHs in the samples at P2 were anthracene> benzo(a) anthracene>pyrene>phenanthrene>acenapthene>chrysene as shown in Figure 2.

Fig. 2: Bar chart representation of the mean levels of the investigated PAHs in the soil samples at P2 situated around fuel stations in Nibo, Awka South L.G.A., Anambra State.

This result indicates that a comparable levels of contamination of the soil samples with the investigated high molecular weight and low molecular weight PAHs. Both sites P1 and P2 had economic crops grown on them and therefore the possibility of the uptake of these PAHs by the plants through their roots remains very high. The mean levels of the PAHs in soil samples at P2 were within the recommended threshold limits and equally differed significantly at p <0.05. Result of Table 1 shows that the mean levels of phenanthrene , chrysene , pyrene and benzo(a) anthracene in the control soil samples were 0.04±0.02 ,0.02± 0.01 ,0.07±0.02 and 0.06±0.01mg/kg respectively. The investigated PAHs decreased in the control soil samples in the following order; pyrene> benzo(a) anthracene> phenanthrene> chrysene as shown in Figure 3.

Fig.3: Bar chart representation of the mean levels of the PAHs in the control soil samples in Nibo, Awka South L.G.A., Anambra State.

The result indicated a higher contamination of the control soil samples with the investigated high molecular weight PAHs compared to the low molecular weight PAHs. The control soil samples contained the determined PAHs within the recommended permissible limits and the mean levels of the PAHs in the soil samples were statistically significant.

The mean levels of 0.98±0.25 and 0.62±0.11mg/kg reported for acenapthene and benzo(a)anthracene respectively by [19] in soil samples from auto-mechanic workshops at Alaoji Aba and Elekhia, Port Harcourt, was higher than what was obtained for the PAHs in the soils at the investigated sites P1 , P2 and control in Nibo. [20] reported a lower mean values of 0.06±0.02 and 0.02±0.01 mg/kg for benzo(a) anthracene and pyrene respectively in soils around the vicinity of petrol stations in Kogi State, than what was gotten for the PAHs in the soil samples of this study.

According to [6], when LMW/HMW is greater than 1, phenanthrene/anthracene is greater than 15 , anthracene/228 is less than 0.2 ,chrysene/benzo(a)anthracene is less than 0.4, anthracene/ anthracene+phenanthrene is less than 0.1 and benzo(a) anthracene/ benzo(a) anthracene+chrysene is less than 0.2, then the sources of the contamination within such an environment would be petrogenic , otherwise pyrolytic source of contamination would be confirmed.

Table 2: The investigated PAHs diagnostic ratio for the soil samples at P1, P2 and control in Nibo, Awka South L.G.A., Anambra State.

| PAH Site | Ant/Ant+phen | LMW/HMW | Phen/Ant | B(a)A/ 288 | Chry/B(a)A | Ant/ 178 | B(a)A/B(a)+Chry |

| P1 | 062 | 0.33 | 0.62 | 0.00 | 1.35 | 0.00 | 0.43 |

| P2 | 0.56 | 1.14 | – | 0.00 | 0.26 | 0.00 | 0.80 |

| Control | – | 0.26 | – | 0.00 | 0.29 | – | 0.75 |

Ant denotes anthracene ; Phen denotes phenanthrene ; LMW denotes low molecular weight PAHs; HMW denotes high molecular weight PAHs; B(a)A denotes benzo(a) anthracene; Chry denotes chrysene.

Based on the findings of [6], it can be inferred from Table 2 that the contamination sources of the soil samples at site P1 were predominantly pyrolytic rather than petrogenic. This observation aligns well with the results reported by [21]. Similar patterns of PAH sources were observed in the soil samples from site P2 and the control site. This suggests that the soils around P1 and P2 experienced minimal or no hydrocarbon (fuel) spillage during discharge or dispensing. Consequently, evaporated hydrocarbons contributed negligibly to soil contamination, with most PAHs arising from the combustion and degradation of organic materials in the study environments.

Conclusion

The majority of the investigated PAHs were detected in soils surrounding fuel stations in Nibo, Awka South L.G.A., Anambra State. The mean concentrations of PAHs in soil samples from sites P1, P2, and the control site were significant, yet all values remained within the recommended permissible limits. The soils were predominantly contaminated with high molecular weight PAHs compared to low molecular weight PAHs. Furthermore, contamination at P1, P2, and the control site was mainly attributed to pyrolytic sources rather than petrogenic sources.

It is therefore important to discourage indiscriminate burning of organic and inorganic materials on soils intended for agricultural use. Additionally, unplanned siting of petrol stations near residential areas and farmlands should be avoided to reduce human exposure to PAHs through food and non-food sources.

Conflict of interest

The authors bears no conflict of interest in the publication of this paper.

References

- Abdel-Shafy H.I. and Mansoor M.S.M (2016). A review on polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons: source , environmental impact, effect on human health and remediation. Egyptian Journal of Petroleum , 25: 107-123.

- Kanaly R.A. and Harayama S.( 2000). Biodegradation of high molecular weight polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons by bacteria. Journal of Bacteriology , 182 (8): 2059-2067.

- Ogoko E.C.(2014). Evaluation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, total petroleum hydrocarbons and some heavy metals in soils of NNPC oil depot Aba metropolis, Abia State, Nigeria. IOSR Journal of Environmental Science , Toxicology and Food Technology, 8(5): 21-27.

- Igwo-Ezikpe M.N., Gbenhe O.G., Ilori M.O., Okpuzor J. and Osuntoki A.A. ( 2010). High molecular weight polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons biodegradation by bacteria isolated from contaminated soils in Nigeria. Research Journal of Environmental Sciences, 4:127-137.

- Aralu C.C., Okoye P.A.C., Akpomie K.G., Okorie H.O. and Abugu H.O. (2022). Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in soils situated around solid waste dumpsite in Awka, Nigeria. Toxin Reviews, 22:349-357.

- Itodo A.U., Akeju T.T. and Itodo H. U.(2019). Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in crude oil contaminated water from Ese-Odo offshore, Nigeria. Annals of Ecology and Environmental Science , 3:12-19.

- Osuji C. and Nwoye I.(2007). An appraisal of the impact of petroleum hydrocarbons on soil fertility: The Onaza experience . African Journal of agricultural Research, 2: 318-324.

- Nam J.J., Song B.H., Eom K.C., Lee S.H. and Smith A. (2003). Distribution of polyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in agricultural soils in South Korea. Chermosphere, 50:1281-1289.

- Odoh B.I., Egboka B.C.E. and Aghamelu P.O. (2012). The status of soil at the permanent site of the Nnamdi Azikiwe University, Awka, South Eastern Nigeria. The Canadian Journal of Pure and Applied Sciences, 6(1): 1837-1845.

- Shitandayi A., Orata F., and Lisouza F.(2019). Assessment of environmental sources, levels and distribution of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons within Neola catchment area in Kenya. Journal of Environmental Protection, 10 (6): 772-790.

- Gammon M.D. and Santella R.M. ( 2008). PAH, genetic susceptibility and breast cancer: An update from the long island breast cancer study project. European Journal of Cancer,44:636-640.

- National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (2001). Hazard review; health effects of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in the soil of Tokushima, Japan. Water, Air and Soil Pollution, 139:51-60.

- Ameh E. G. (2014). A preliminary assessment of soil samples around filling station in Diobu,Port Harcourt, Rivers State, Nigeria. Research Journal of Environmental and earth Sciences , 6:57-65.

- Mschella A.M., John A. and Emmanuel D.D. (2015). Environmental effects of petrol stations at proximity to residential buildings in Maiduguri and Jere, Borno State, Nigeria. IOSR Journal of Humanities and Social sciences, 20:1-8.

- Associatio of Official Analytical Chemists (2016). Official method of analysis of AOAC. 20th edn. Washington D.C. 770-776.

- Mirza P., Faghiri I. and Abedi E. (2012). Contamination of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in surface sediments of Khure-Musa Estuarine, Parsian Gulf. Worl Hournal of Fish and Marine Sciences, 4(2): 136-141.

- Polish Environmental Protection Agency (2002). Quality standards of sois due to PAHs. D.Z.U.No 165: 135-163.

- World Health Organization (2002). Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons .In: Air quality guidelines for Europe. 105-107.

- Muzie N.E., Opara A.I., Ibe F.C. and Njoku O.C. (2020). Assessment of the geo-environmental effects of ctivities of auto-mechanic workshops at Alaoji Aba and Elekahlia , Port Harcourt, Niger-Delta, Nigeria. Environmental Analysis of Health and Toxicology, 35(2) : 1-12.

- Kadili J.A., Eneji I.S., Itodo A.U. and Ado R.S. ( 2021). Concentration and risk evaluation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in soils from the vicinity of selected petrol stations in Kogi State , Nigeria. Open Access Library Journal, 8:106-124.

- Adeniji A.O., Okoh O.O. and Okoh A.I. (2018). Analytical methods for polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and their global trend of distribution in water and sediment: A review. Recent Insights in Petroleum Science and Engineering , 76(4) : 657-669.