Introduction: Over the past three decades, synthetic chemists have been striving to improve human life by minimizing chemical pollution. Significant research efforts have focused on designing chemicals and synthetic processes that are less harmful to human health and the environment by employing environmentally benign methodologies of chemical synthesis. Techniques such as microwave-assisted syntheses, catalyst-mediated reactions, and solvent-free or green-solvent-based syntheses for coordination compounds have emerged as particularly important eco-friendly approaches.

A review of the literature reveals that azomethine compounds, i.e., Schiff bases, exhibit excellent complexation ability toward transition metal ions and possess a wide range of applications across various fields, making them highly significant in the development of coordination chemistry. Current research trends on azomethine complexes have increasingly focused on exploring their antimicrobial and other therapeutic activities. Given the numerous applications of Schiff bases, there has been growing interest among chemists in developing efficient and sustainable methods for their synthesis, as well as the synthesis of their transition metal complexes. In this context, microwave-assisted reactions have proven to be a facile, efficient, and eco-friendly approach for the preparation of various Schiff bases and their metal complexes.

As part of our ongoing efforts to synthesize and characterize transition metal complexes using azomethine ligands under environmentally benign conditions, the present study reports the microwave-assisted synthesis, characterization, and antimicrobial evaluation of Ni(II) complexes of the NOO′N donor ligand o-phenylene-bis(o-hydroxy acetophenone) diamine as the primary ligand, along with quinoline, pyridine, and various monodentate secondary ligands. This research includes a comparative study of the Schiff base and Ni(II) complexes synthesized via conventional and eco-friendly methods. Although single crystals of the investigated compounds could not be obtained from any solution, analytical data, magnetic measurements, and spectroscopic studies have enabled us to propose plausible geometries for the synthesized complexes.

EXPERIMENTAL

Materials & Methods

All chemicals used for the synthesis of the ligand and its complexes were of analytical grade. The solvents employed were purified according to previously established standard procedures. Melting points of the synthesized compounds were determined using an Electro-thermal 9100 apparatus and are reported as uncorrected. Conductivity measurements of the complexes were performed in DMF using a Philips PW 9515/10 conductivity cell with a PW 9501 bridge model. Magnetic susceptibility measurements were carried out by Gouy’s method, using Hg[Co(NCS)₄] (χg = 16.44 × 10⁻⁶) as a reference standard. Elemental analyses were conducted on a Carlo-Erba EA1110 CHNO-S analyzer.

Electronic spectra of the ligand and complexes were recorded in both solid state and solution using a Shimadzu UV-Visible spectrophotometer. Infrared spectra were obtained in the range 4000–400 cm⁻¹ using KBr discs on a Shimadzu IR spectrophotometer. Microwave-assisted syntheses were performed in a modified common microwave oven (model 2001 ETB) equipped with a rotating tray, operating at 230 V, 800 W output power, and a frequency of 2450 MHz. Temperature control during microwave reactions was maintained using an on/off cycling method. The reaction progress and product purity were monitored by thin-layer chromatography (TLC) on pre-coated silica gel GF254 plates (E-Merck) using suitable solvent systems.

The antimicrobial activities of the ligand and the synthesized complexes were evaluated using the disc diffusion method, with nutrient agar as the medium for antibacterial testing and Sabouraud dextrose agar for antifungal activity.

Microwave assisted synthesis of Ligand

The eco-friendly, cost-effective approach, combined with faster reaction rates, reduced use of hazardous chemicals, low cost, higher yields, and simplicity in processing and handling, motivated us to synthesize the ligand using a green solvent, specifically a 1:1 mixture of ethanol and water, in a modified microwave oven. A 1:2 molar mixture of o-hydroxy acetophenone and o-phenylenediamine in the aqueous-ethanolic mixture was refluxed at ambient temperature in the microwave oven for six minutes and then allowed to cool, yielding a yellowish solid. The resulting solid was washed with ethyl alcohol, recrystallized from acetone, and finally dried under reduced pressure over anhydrous CaCl₂ in a desiccator. The reaction was completed in a short time, producing a better yield (approximately 77%) compared to that obtained using the conventional method (Scheme-1). A comparison of the yield and reaction time for both the conventional and green synthesis approaches is presented in Table-1.

Scheme-1:Microwave assisted synthesis of ligand

Synthesis of Metal Complexes

The Ni(II) complexes under investigation were synthesized by refluxing a stoichiometric mixture (1:1:2, metal: primary ligand (L): secondary ligand (L′)) of NiCl₂·6H₂O, primary ligand (L), and secondary ligands (L′) in an aqueous-ethanolic medium using a microwave oven, with a few drops of triethylamine added as a catalyst. The reactions were completed rapidly, within 5–12 minutes, and yielded better results compared to conventional methods (Scheme 2). The resulting colored solid products were isolated by filtration, recrystallized from DMF, washed with ethanol, and finally dried under reduced pressure over anhydrous CaCl₂ in a desiccator. The progress of the microwave-assisted reactions and the purity of the products were monitored using TLC on silica gel G, with yields ranging from 56 to 70%.

Scheme-2: Microwave assisted synthesis of Ni(II)-complexes

(where, L’ = H2O, NH3, Quinoline, phenyl isocyanide, pyridine, picolines etc. and M=Ni)

Antimicrobial Activity

The antibacterial and antifungal activities of the studied ligand and its Ni(II) complexes were evaluated using the disc diffusion method. The in vitro antibacterial activity was tested against two Gram-positive bacteria, Staphylococcus aureus (SA) and Enterococcus faecalis (EF), and two Gram-negative bacteria, Escherichia coli (EC) and Staphylococcus mutans (SM). Antifungal activity was assessed against Candida albicans (CA) and Aspergillus niger (AN). Chloramphenicol and griseofulvin were used as standard reference drugs for bacteria and fungi, respectively, at the same concentrations under identical conditions.

The test compounds were dissolved in DMSO, which showed no inhibition activity, to prepare a concentration of 1 mg/mL. Sterile discs were then soaked in the test solutions and carefully placed on the surface of inoculated agar plates. The plates were incubated for 24 hours at 37 °C for bacterial strains and 48 hours at 37 °C for fungal strains. After incubation, the zones of inhibition were measured precisely. Each experiment was performed in triplicate, and the average values are reported in Table 4.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

All the complexes synthesized using microwave-assisted methods are colored, solid, and stable to air and moisture at room temperature. They do not exhibit sharp melting points and decompose upon heating at temperatures higher than their respective melting ranges. The investigated complexes are insoluble in common organic solvents. Spectral and microanalytical data confirm that the composition of all the synthesized metal complexes corresponds to a [NiL(L′)₂] stoichiometry. The observed molar conductance values (12–22 Ω⁻¹ cm² mol⁻¹) are very low, indicating negligible dissociation of the complexes in DMF at room temperature, and confirming their non-electrolytic nature. Experimental results further demonstrate that the microwave-assisted synthesis allows the reactions to reach completion in a shorter time and with higher yields compared to conventional thermal methods. A comparison of the results from conventional and microwave-assisted procedures, including analytical data and physical properties of the complexes—which are consistent with the proposed molecular formula—is presented in Table 1

Table-1: Comparison of conventional and microwave assisted method, analytical and physical data of the compounds under investigation

| Compounds (Colour) | Reaction Time CM (MM) | Yield (%) CM (MM) | Mol. Weight | Melting point (in K) | Elemental analysis Calculated (Found) % | μeff (BM) | Conductance (ohm-1 cm2 mol-1) | |||

| C | H | N | Ni | |||||||

| C22H20N2O2 (pale yellow) | 2 hrs. (6 min.) | 60 (77) | 344 | 512 | 76.74 (76.70) | 5.81 (5.80) | 8.13 (8.10) | — | — | 20 |

| [Ni(C22H18N2O2)(H2O)2] (green) | 2.5 hrs. (5min.) | 57 (70) | 436.69 | 565 | 60.45 (60.40) | 5.03 (5.08) | 6.41 (6.40) | 13.44 (13.50) | 3.20 | 22 |

| [Ni(C22H18N2O2)(NH3)2] (light green) | 2.5 hrs. (6 min.) | 40 (65) | 434.69 | 579 | 60.73 (60.70) | 5.52 (5.50) | 12.89 (12.90) | 13.50 (13.50) | 3.24 | 15 |

| [Ni(C22H18N2O2)(C5H5N)2] (faint green) | 2.5 hrs. (8 min.) | 41 (66) | 558.69 | 623 | 68.73 (68.70) | 5.01 (5.05) | 10.04 (10.00) | 10.51 (10.50) | 3.26 | 12 |

| [Ni(C22H18N2O2)(C9H7N)2] (greenish white) | 2.5 hrs. (10 min.) | 44 (67) | 658.69 | 589 | 72.86 (72.80) | 4.87 (4.84) | 8.50 (8.50) | 8.91 (8.90) | 3.28 | 16 |

| [Ni(C22H18N2O2)(C6H5NC)2] (light green) | 2.5 hrs. (10 min.) | 53 (68) | 606.69 | 594 | 67.24 (67.20) | 4.62 (4.60) | 9.24 (9.20) | 9.67 (9.70) | 3.32 | 13 |

| [Ni(C22H18N2O2)(C5H4NCH3)2] (faint green) α-picoline | 2.5 hrs. (12 min.) | 41 (70) | 586.69 | 584 | 69.53 (69.50) | 5.46 (5.40) | 9.55 (9.50) | 10.00 (10.00) | 3.20 | 12 |

| [Ni(C22H18N2O2)( C5H4NCH3)2] (faint green) β-picoline | 2.5 hrs. (12 min.) | 33 (56) | 586.69 | 605 | 69.53 (69.50) | 5.46 (5.40) | 9.55 (9.50) | 10.00 (10.00) | 3.18 | 18 |

| [Ni(C22H18N2O2)( C5H4NCH3)2] (faint green) λ-picoline | 2.5 hrs. (12 min.) | 41 (70) | 586.69 | 595 | 69.53 (69.50) | 5.46 (5.40) | 9.55 (9.50) | 10.00 (10.00) | 3.20 | 14 |

CM = Conventional Method; MM = Microwave Method

IR Spectral Studies

The IR spectral data of the investigated Schiff base ligand (L) and its eight Ni(II) complexes synthesized via microwave-assisted methods are presented in Table 2. The IR spectra of the complexes were compared with that of the free ligand to identify the involvement of specific coordination sites. The spectra of the complexes retained most of the characteristic absorption bands of the ligand, with some new bands and shifts observed, indicating coordination of the ligand to the metal ion through nitrogen and oxygen atoms.

Comparison of the IR spectra of the ligand precursor, o-hydroxy acetophenone, and the Schiff base ligand itself reveals the disappearance of the characteristic ketonic carbonyl stretching band near 1750 cm⁻¹ and the appearance of the azomethine (–C=N) stretching band at 1630 cm⁻¹, confirming the formation of the Schiff base.

Upon complexation, significant shifts were observed in the frequencies corresponding to the (O–H), (C=N), and (C–N) groups of the ligand. In all complexes, the hydroxyl band at 3360 cm⁻¹ in the ligand disappears, indicating deprotonation and coordination of the phenolic oxygen to the metal center. This deprotonation is further supported by the shift of the phenolic (C–O) stretching from 1420–1430 cm⁻¹ in the ligand to 1450–1460 cm⁻¹ in the complexes. The decrease in the azomethine (C=N) frequency from 1630 cm⁻¹ to 1580 cm⁻¹ suggests involvement of the nitrogen atom in coordination, while the reduction in the C–N frequency from 1240 cm⁻¹ to 1220 cm⁻¹ indicates coordination through the aldimino nitrogen. Overall, these observations confirm that the ligand functions as a bi-anionic tetradentate (NOO′N) donor.

In aqua complexes, the ν(OH) and ν(NH) vibrations overlap, making it difficult to observe a distinct band for coordinated water; however, a band at 750 cm⁻¹ is attributed to the rocking mode of coordinated H₂O. In the amino complex, a broad band around 3460 cm⁻¹ corresponds to the (NH) stretching vibration of coordinated NH₃. In the phenyl isocyanide complex, an increase in the ν(C≡N) stretching from 2170 cm⁻¹ (ligand) to 2220 cm⁻¹ (complex) confirms the involvement of the isocyanide (N≡C) group in coordination. In the quinoline complex, a medium broad band around 1680 cm⁻¹ indicates coordination through the nitrogen atom of quinoline. Pyridine and picoline complexes show characteristic bands in the fingerprint and far-infrared regions; coordinated pyridine exhibits bands at 1000–1100 cm⁻¹, whereas different picoline molecules display bands at 790, 770, and 750 cm⁻¹.

Furthermore, sharp to medium bands in the range of 420–435 cm⁻¹ in the complexes are assigned to ν(M–N) vibrations, confirming coordination of the aldimino nitrogen atoms to the metal. Bands observed at 450–475 cm⁻¹ correspond to ν(M–O) vibrations, confirming the coordination of the phenolic oxygen. The higher frequency of the M–O vibration compared to M–N reflects the more ionic nature of the metal–oxygen bond relative to the metal–nitrogen bond.

Table-2: Observed IR bands (cm-1) of Ligand and their Ni-complexes

| Bands (cm-1) of Ligand | Bands of complexes | Probable assignment |

| — | 3480 | ν(N-H) |

| 3360 | ν(O-H) | |

| 1630 | 1580 | ν(C=N) |

| 1420 | 1450 | ν(O-H) phenolic |

| 1240 | 1220 | ν(C-N) |

| 1680 | ν(C=N)Quinoline | |

| 2220 | ν(-NC) | |

| 1050 | Due to pyridine ring | |

| 790 | α-picoline | |

| 750 | β-picoline | |

| 760 | λ-picoline | |

| 450-475 | ν(M-O) | |

| 420-435 | ν(M-N) |

Electronic Spectral Studies & Magnetic Properties

The electronic spectra of ligand and its investigated nickel complexes were recorded in order to assign the plausible geometry around the central metal ion in the complexes. The electronic spectra of the ligand and its nickel complexes in DMF were scanned in the region 200-1000 nm and their tentative assignments are presented in table-3.

Table-3: Data of electronic spectra of the ligand (L) and its Ni(II) complexes

| Complexes | ν1 (cm-1) | ν2 (cm-1) | ν3 (cm-1) | Charge Transfer Band |

| C22H20N2O2 | 13850 | — | — | 28300 |

| [Ni(C22H18N2O2)(H2O)2] | 8210 | 16400 | 22640 | 29600 |

| [Ni(C22H18N2O2)(NH3)2] | 8150 | 16200 | 21750 | 31300 |

| [Ni(C22H18N2O2)(C5H5N)2] | 8090 | 16200 | 21420 | 32700 |

| [Ni(C22H18N2O2)(C9H7N)2] | 8100 | 21250 | 21250 | 33100 |

| [Ni(C22H18N2O2)(C6H5NC)2] | 8130 | 15700 | 21930 | 33900 |

| [Ni(C22H18N2O2)(C5H4NCH3)2] | 8110 | 16000 | 21840 | 33500 |

| [Ni(C22H18N2O2)( C5H4NCH3)2] | 8130 | 15600 | 22630 | 33200 |

| [Ni(C22H18N2O2)( C5H4NCH3)2] | 8100 | 16000 | 21610 | 34100 |

All the investigated Ni(II) complexes, [Ni(L)(L’)₂], exhibit a strong absorption band in the range of 28,300–34,100 cm⁻¹, which is attributed to a ligand-to-metal charge transfer (LMCT). In addition, three d–d transition bands were observed: the first, broad and asymmetric band appears between 8,090–8,210 cm⁻¹ and is assigned to the ³A₂g(F) → ³T₂g(F) transition, influenced by Jahn–Teller distortion. The second band, sharp and symmetric, occurs in the range of 15,400–16,400 cm⁻¹ and corresponds to the ³A₂g(F) → ³T₁g(F) transition, which is both spin- and symmetry-allowed. The third sharp and symmetric band appears between 21,250–22,640 cm⁻¹, attributed to the ³A₂g(F) → ³T₁g(P) transition, also spin- and symmetry-allowed. These electronic transitions are consistent with a spin-allowed octahedral geometry for all the investigated Ni(II) complexes.

The magnetic moment values of the complexes, ranging from 3.18 to 3.32 B.M., further support their octahedral geometry.

Proposed Geometry of Ni(II) Complexes

Based on the spectral and magnetic data, the investigated Ni(II) complexes are tentatively proposed to adopt an octahedral geometry [Figure 1], where the primary ligand (L) functions as a dibasic tetradentate donor (NOO′N). Elemental analysis and molecular weight determinations confirm the monomeric nature of these complexes.

Figure-1: Proposed octahedral geometry of investigated Ni-complexes

Studies of Antimicrobial Activities

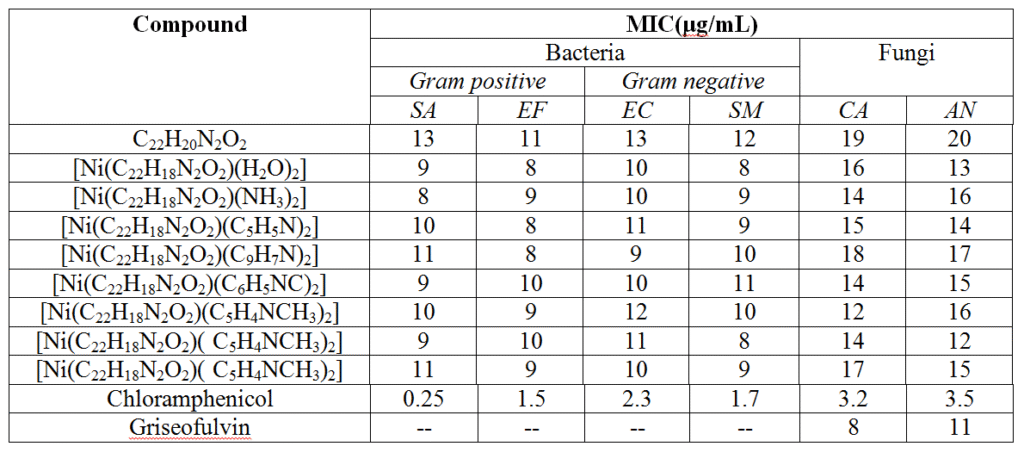

The difference in the antimicrobial activities of the ligand and its investigated Ni(II) complexes were studied and the results are presented in table-4. The comparison of MIC (minimum inhibitory concentration) values of investigated ligand and its nickel complexes indicates that generally all complexes have a better activity than the free ligand which may be probably due to their lipophilic nature and it can be explained on the basis of chelation theory22. Further, the antimicrobial results show that the activity of ligand has increased on coordination to the central metal ion of the investigated Ni(II)-complexes.

Table-4:In vitro Antimicrobial Activity of the ligands and their Co-complexes (in μgmL-1)

CONCLUSIONS

A new biologically active ligand was efficiently and conveniently synthesized in a single step by reacting o-hydroxyacetophenone with o-phenylenediamine in an aqueous-ethanol medium, serving as a green solvent. Its Ni(II) complexes, containing potential pharmacophoric sites, were prepared using an environmentally benign microwave-assisted protocol. The microwave method yielded higher product amounts and required significantly less reaction time compared to conventional methods.

The synthesized ligand coordinated to the Ni(II) ion in a tetradentate (NO O′N) fashion. Based on elemental analysis, molar conductance, magnetic susceptibility, and electronic and IR spectral data, an octahedral geometry was proposed for the Ni(II) complexes. Antimicrobial studies indicated that the metal complexes exhibited enhanced antibacterial and antifungal activities compared to the free ligand.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- Chohan, Z. H.; Arif, M.; Akhtar, M. A.; Supuran, C.T.; Bioinorganic Chemistry and Applications, 2006, 1-11.

- Anastas, P.; Heine, L. G.; Williamson, T. C.; Green Chemical Synthesis & Process, 2000, Oxford University, Press, N Y.

- Sheldon, R. A.; “Matrices of Green Chemistry and Sustainability: Past, Present and Future”, ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng., 2018, 6, 32-48.

- Leadbeater, N.E.; Microwave Heating as a tool for Sustainable Chemistry, 2010, CRC Press, Boca Raton, Florida, USA.

- Polshettiwar, V.; Aqueous Microwave Assisted Chemistry: Synthesis and Catalysis, 2010, RSC, Cambridge, UK.

- Vigato, P. A.; Tamburini, S.; Coord.Chem. Rev., 2004 ,248, 1717-2128.

- Radecka-Paryzek, W.; Patroniak, V.; Lisowski, J.; Coord.Chem. Rev., 2005, 249, 2156-2175.

- Gupta, K. C.; Sutar, A. K.; Coord.Chem. Rev., 2008, 52 (12-14), 1420-1450.

- Srivastava, K.P.; Anuradha Singh; Suresh Kumar Singh; IOSR Journal of Applied Chemistry, 2014, 7(4), 16-23.

- Srivastava, K.P.; Sunil Kumar Singh; Bir Prakash Mishra; Der Pharma Chemica, 2015, 7 (1), 121-127.

- Srivastava, K.P.; Anuradha Singh; IOSR-Journal of Applied Chemistry, 2016, 9, 11 (III), 01-06.

- Srivastava, K.P.; Putul, O.P.; Nagendra Kumar; Der Pharma Chemica, 2016, 8(3):105-116.

- Srivastava, K.P.; Anuradha Singh; Journal of Applicable Chemistry, 2017, 6 (4), 599-606.

- Greenwood, D.; Snack, R.; Peurtherer, J.; Medical microbiology: A guide to microbial infections: Pathogenesis, immunity, laboratory diagnosis and control, 15th edn. 1997.

- Geary, W. J.; Coord. Chem. Rev., 1971, 7, 81.

- K. Nakamoto; Infrared spectra of Inorganic and Coordination Compounds; 1970, 2nd edn. Wiley-Intersciences, New York.

- Bellamy, L. J.; The Infrared Spectra of complex molecules; 1975, 3rd edn. Chapman and Hall, London, Vol. 233.

- Adams, D. M.; Metal-ligand and related vibrations, Edward Arnold, London, 1967, 248 & 284.

- Sathynarayana, D. N.; Electronic absorption spectroscopy and Related Techniques, 2001, Universities Press Ltd., India.

- Ballhausen C. J.; An Introduction to Ligand Field Theory, 1962, Mc Grew-Hill, NY.

- Dutta, R. L.; Syamal, A.; Elements of Magnetochemistry, 1993, Affiliated East West Press, New Delhi ().

- Tweedy, B. G.; Phytopatholo., 1964, 55, 910.