1. Introduction

The rapid rise of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is recognized as one of the greatest threats to global health in the 21st century. Traditional antibiotics are increasingly ineffective against multidrug-resistant pathogens, necessitating the development of alternative strategies to combat infections. Nanotechnology offers innovative solutions, particularly through the design and application of metal and metal oxide nanoparticles with intrinsic antimicrobial activity.

Nickel oxide (NiO) nanoparticles represent one of the less-explored yet highly promising nanomaterials in this regard. NiO is a p-type semiconductor with a wide band gap (~3.6–4.0 eV), notable redox activity, and strong catalytic properties. Beyond traditional applications in catalysis, fuel cells, and sensors, NiO has demonstrated antimicrobial efficacy against a wide spectrum of Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, positioning it as a potential agent in biomedical and pharmaceutical applications.

This review consolidates current knowledge on NiO nanoparticles, with emphasis on synthesis methods, structural and morphological characterization, antibacterial activity, mechanistic insights, and future biomedical applications.

2. Overview of Nickel Oxide Nanoparticles

2.1 General Properties

- Rock-salt cubic structure

- Band gap ~3.6–4.0 eV

- p-type semiconducting nature

2.2 Comparison with Other MONPs

Table 1. Comparison of selected properties of common metal oxide nanoparticles

| Nanoparticle | Band gap (eV) | Antimicrobial Mechanism | Relative Cost | Biomedical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NiO | 3.6–4.0 | ROS generation, Ni²⁺ release, membrane disruption | Low | Antibacterial coatings, biosensors |

| ZnO | 3.3 | ROS + Zn²⁺ release | Moderate | Sunscreens, wound healing |

| TiO₂ | 3.0–3.2 | Photocatalysis (UV) | Low | Photodynamic therapy, implants |

| Ag₂O/AgNPs | — | Ag⁺ release, membrane binding | High | Strong antibacterial, wound healing |

3. Synthesis Methods of NiO Nanoparticles

3.1 Thermal Decomposition

- Simple and reproducible [Santhoshkumar et al., 2017].

3.2 Sol–Gel

- Produces uniform nanoparticles; widely reported [Yan et al., 1996].

3.3 Hydrothermal / Solvothermal

- Can yield unique morphologies (flowers, rods) [Wang et al., 2002].

3.4 Precipitation

- Economical but agglomeration-prone [Che et al., 1999].

3.5 Electrospinning

- Produces nanofibers for biomedical coatings [Xiang et al., 2002].

3.6 Green Synthesis

- Plant-based reducing agents reduce environmental impact [Suresh et al., 2018].

Table 2. Synthesis techniques and typical NiO nanoparticle features

| Method | Morphology Obtained | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thermal decomposition | Nanocrystals (40–80 nm) | Simple, low cost | Agglomeration |

| Sol–gel | Uniform spheres/rods | High purity, control | Longer processing time |

| Hydrothermal | Nanorods, nanoflowers | High crystallinity | Requires high pressure |

| Electrospinning | Nanofibers | Good for coatings | Limited scalability |

| Green synthesis | Variable (depends on extract) | Eco-friendly, biocompatible | Reproducibility issues |

4. Characterization of NiO Nanoparticles

Table 3. Summary of key characterization techniques for NiO nanoparticles

| Technique | Information Provided | Example Observations |

|---|---|---|

| XRD | Phase purity, crystallite size | Rock-salt NiO, ~42 nm crystallites [Santhoshkumar et al., 2017] |

| FTIR | Functional groups, bonding | Ni–O stretching ~1499 cm⁻¹ |

| SEM/TEM | Morphology, size | Agglomerated nanoparticles, 80–130 nm |

| EDS | Elemental composition | Ni:O ratio ~1:1 |

| UV–Vis | Band gap energy | ~3.8 eV |

| BET | Surface area, porosity | 20–80 m²/g depending on synthesis |

5. Mechanisms of Antimicrobial Action

- ROS production (hydroxyl radicals, superoxide anions) damages DNA and proteins [Sawai et al., 1996].

- Membrane interaction leads to cell lysis [Li et al., 2016].

- Ni²⁺ ion release contributes to toxicity.

- Synergy with antibiotics: NiO + tetracycline shows enhanced activity [Gurunathan et al., 2019].

6. Comparative Antibacterial Activity

Table 4. Antibacterial performance of NiO nanoparticles

| Study | Pathogen Tested | Method | Zone of Inhibition (mm) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Santhoshkumar et al., 2017 | B. subtilis, S. aureus, E. coli, P. vulgaris | Agar well diffusion | 19–22 mm | Thermal decomposition NiO |

| Davar et al., 2009 | E. coli | Disk diffusion | 18 mm | Sol–gel NiO |

| Li et al., 2016 | S. aureus, P. aeruginosa | MIC assay | MIC = 25–50 µg/mL | Dose-dependent activity |

| Singh et al., 2012 | B. subtilis | Sonochemical method | 20 mm | ROS-driven inhibition |

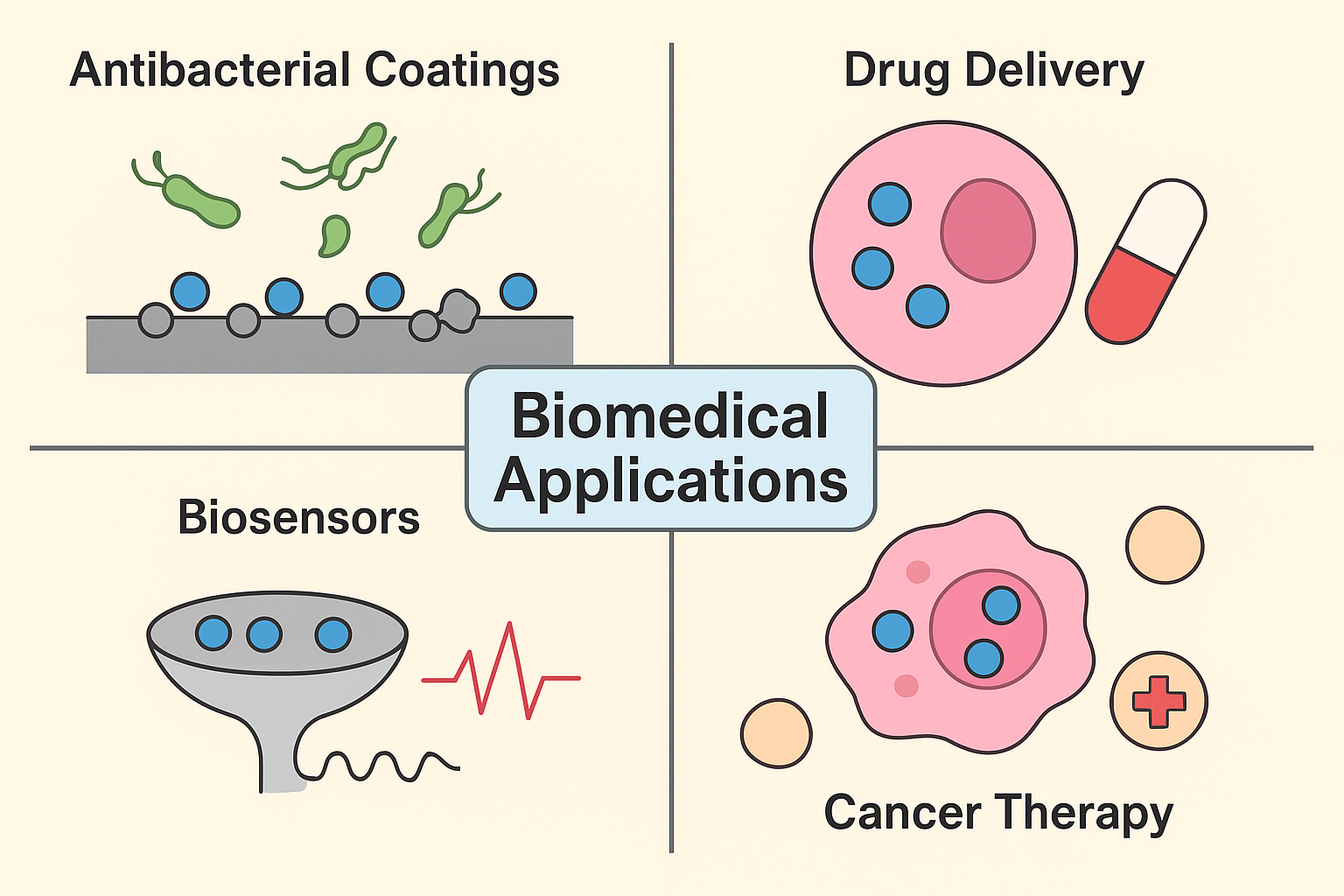

7. Biomedical Applications

- Antibacterial coatings: NiO coatings on surgical steel show reduced biofilm formation.

- Drug delivery: NiO as nanocarriers for anticancer drugs [Al-Salami et al., 2020].

- Cancer therapy: ROS-mediated apoptosis in tumor cells [Sharma et al., 2019].

- Sensors: NiO-based glucose and DNA biosensors [Umar & Hahn, 2006].

Application schematic – coatings, drug delivery, biosensors, cancer therapy.

8. Toxicity and Biocompatibility

- Cytotoxicity reported in mammalian cells at concentrations >50 µg/mL [Boyanova et al., 2005].

- Inhalation exposure linked with pulmonary inflammation [EPA Report, 2015].

- Strategies for reducing toxicity:

- Surface coating with PEG/chitosan,

- Embedding in biopolymers,

- Using green synthesis to avoid harmful residues.

Table 5. Reported toxicity studies of NiO nanoparticles

| Study | Model | Dose | Observed Effects |

|---|---|---|---|

| Li et al., 2016 | Plant cells | 50 mg/L | Oxidative stress, membrane leakage |

| Gurunathan et al., 2019 | Human cell lines | 10–100 µg/mL | Dose-dependent cytotoxicity |

| Sharma et al., 2019 | Mice (in vivo) | 5–20 mg/kg | Inflammation, ROS accumulation |

9. Future Prospects and Challenges

- Scaling up green synthesis.

- NiO-based hybrid nanomaterials with graphene, polymers, silver.

- Clinical testing against multi-drug resistant (MDR) pathogens.

- Regulatory frameworks for nanotoxicology.

10. Conclusion

Nickel oxide nanoparticles are emerging as powerful multifunctional nanomaterials with significant antimicrobial potential. The versatility in synthesis methods allows tailoring of their physicochemical properties for diverse applications. While challenges regarding toxicity and clinical translation remain, continuous research is expected to expand their role in nanomedicine, particularly in combating antimicrobial resistance. NiO nanoparticles, with their cost-effectiveness and potent biological activity, could soon join the forefront of nano-enabled healthcare technologies.

References

- S.M. Dizaj, F. Lotfipour, M. Barzegar-Jalali, M.H. Zarrintan and K. Adibkia, Mater. Sci. Eng., 44, 278 (2014).

- M. Guziewicz, W. Jung, J. Grochowski, M. Borysiewicz, K. Golaszewska,R. Kruszka, B.S. Witkowski, J. Domagala, M. Gryzinski, K. Tyminska,

P. Tulik and A. Piotrowska, Process. Eng., 25, 367 (2011). - A. Azens, L. Kullman, G. Vaivars, H. Nordborg and C.G. Granqvist, Solid State Ion., 113-115, 449 (1998).

- W. Shin and N. Murayama, Mater. Lett., 45, 302 (2000).

- A. Yan, Z. Chen, X. Song and X. Wang, Mater. Res. Bull., 31, 1171 (1996).

- S.L. Che, K. Takada, K. Takashima, O. Sakurai, K. Shinozaki and N. Mizutani, J. Mater. Sci., 34, 1313 (1999).

- W. Wang, Y. Liu, C. Xu, C. Zheng and G. Wang, Chem. Phys. Lett., 362, 119 (2002).

- L. Xiang, X.Y. Deng and Y. Jin, Scr. Mater., 47, 219 (2002).

- L. Boyanova, G. Gergova, R. Nikolov, S. Derejian, E. Lazarova, N. Katsarov, I. Mitov and Z. Krastev, J. Med. Microbiol., 54, 481 (2005).

- A. Umar and Y.B. Hahn, Nanotechnology, 17, 2174 (2006).

- F. Davar, Z. Fereshteh and M. Salavati-Niasari, J. Alloys Comp., 476, 797 (2009).

- G. Singh, E.M. Joyce, J. Beddow and T.J. Mason, J. Microbiol. Biotechnol.,2, 106 (2012).

- J. Sawai, H. Igarashi, A. Hashimoto, T. Kokugan and M. Shimizu,J. Chem. Eng. Data, 29, 251 (1996).

- Y. Li, H. Lu, Q. Cheng, R. Li, S. He and B. Li, Sci. Hortic., 199, 81 (2016).