Introduction: Coconut sap is obtained by tapping the unopened spadix, or young inflorescence, of a coconut tree (Cocos nucifera L.)¹. In Indonesia, particularly in Banyumas Regency, coconut sap is commonly used as the raw material for coconut sugar. Due to its nutritional content, coconut sap undergoes spontaneous fermentation, becoming alcoholic and acidic as a result of microbial activity². Granulated coconut sugar is produced from coconut sap through an extended heating process. A characteristic feature of coconut sugar is its brown color, which develops during heating due to the Maillard reaction. This reaction is crucial in sugar production, affecting flavor, color, and aroma³.

The intensity of the Maillard reaction is influenced by the composition of reactants, namely the reducing sugars and amino acids in the sap⁴, as well as the heating temperature⁵. According to Ho et al.⁶, free amino acids serve as a source of amino groups, free ammonia, or nitrogen atoms through deamination and retro-aldol reactions, while monosaccharides such as glucose and fructose initiate the Maillard reaction by generating highly reactive C2 and C4 dicarbonyl compounds.

The addition of lysine increases the availability of basic amino groups, facilitating the Maillard reaction under alkaline conditions via the 2,3-enolization pathway through 1-deoxy-2,3-dicarbonyl intermediates. This pathway produces reductone compounds with antioxidant activity. Therefore, it is important to investigate how lysine addition affects the chemical and antioxidant properties of coconut sap, generating Maillard reaction products (MRPs) and melanoidins in granulated coconut sugar. These MRPs and melanoidins contribute significantly to the antioxidant activity of the sugar.

Wijewickreme et al.⁷ reported that amino acids and reducing sugars in the Maillard reaction influence food color, flavor, and antioxidant properties. In vitro studies have shown that MRPs may act as antioxidants by functioning as metal chelators and radical scavengers⁸. Yan et al.⁹ observed that MRPs derived from a chitooligosaccharide-glycine model system exhibited strong antioxidant activity, and their addition to fruit juices enhanced antioxidant capacity. Karseno et al.¹⁰ found a significant correlation between browning intensity and DPPH radical scavenging activity (r = 0.93).

The objective of this study was to evaluate the chemical properties and antioxidant activity of granulated coconut sugar supplemented with lysine before the heating process.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials and Chemicals

Coconut sap was collected from the inflorescences of tall coconut trees (Cocos nucifera L.) grown in Sikapat Village, Sumbang District, Banyumas Regency, Central Java, Indonesia, at altitudes of 500–1000 m above sea level. Sap was tapped during daytime (06:00–15:00) in fine weather (24–27 °C) with relative humidity of 91–92%.

Chemicals used included potassium hydrogen tartrate, phenol, sodium sulfite, sodium hydroxide, hydrochloric acid, D-glucose, ninhydrin, dipotassium hydrogen phosphate, potassium dihydrogen phosphate, stannous chloride, L-glutamic acid, ethanol, Folin–Ciocalteu reagent, sodium carbonate, ammonium thiocyanate, ferrous chloride, and hydrochloric acid (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany). Ferrozine was obtained from Fluka Chemical Co. (Buchs, Switzerland), while 3,5-dinitrosalicylic acid and 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) were procured from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO, USA).

Collection of Coconut Sap

Sap was collected from 15 coconut trees. It was accumulated in plastic containers pre-washed with hot water to reduce microbial contamination. Preservatives added were 1.7 g/L lime and 0.56 g/L mangosteen peel powder. The tip of the inflorescence was cut with a sterilized stainless steel knife, and the prepared containers were attached to collect sap. The pH and total soluble solids of the collected sap were immediately measured using a portable refractometer (Atago, Japan). Only sap meeting chemical property requirements for granulated coconut sugar production was processed.

Processing of Granulated Coconut Sugar

Ten liters of sap were filtered through a cloth and divided into four portions: three were supplemented with lysine at 0.25, 0.5, and 0.75 mM, while one remained untreated as a control. Each portion was heated in an aluminum pan over a gas stove for approximately 50 minutes, with continuous agitation until the sap reached 118 °C. The viscous sap was further agitated at room temperature until crystallization occurred, producing granulated sugar. Fifty grams of each sample were collected for chemical and antioxidant analyses.

Chemical Analysis

The granulated coconut sugar samples were analyzed for water content, ash content, reducing sugar, sucrose, total sugar, total free amino acids, total phenolics, browning intensity, DPPH radical scavenging activity, and chelating activity.

Water Content – Measured using a thermogravimetric-based method¹¹.

Ash Content – Determined according to AOAC¹¹ by combusting organic matter at 500–600 °C and weighing the residue.

Reducing Sugar, Total Sugar, and Sucrose – Reducing sugar was determined following Miller¹². One gram of sap was dissolved in 5 mL distilled water; 3 mL of this solution was mixed with 3 mL 1% 3,5-dinitrosalicylic acid reagent, heated at 90 °C for 15 minutes, then stabilized with 1 mL 40% potassium tartrate. Absorbance was measured at 540 nm. Total sugar was determined by hydrolyzing 3 mL of sap with 3 mL 25% HCl at 70 °C for 10 minutes, neutralized with 45% NaOH, and analyzed as reducing sugar. Sucrose content was calculated by subtracting reducing sugar from total sugar.

Free Amino Acids – Determined using Yao et al.’s method¹³. One gram of sap was placed in a 25 mL volumetric flask with 0.5 mL buffer and 0.5 mL ninhydrin, boiled for 15 minutes, cooled, diluted to 25 mL, and absorbance measured at 570 nm. Glutamic acid was used for the standard curve.

Total Phenolics – Estimated using the Folin–Ciocalteu method¹⁴. Thirty microliters of sample were mixed with 150 µL 10% Folin–Ciocalteu reagent and 120 µL 7.5% Na₂CO₃, incubated for 1 hour at 30 °C, and absorbance measured at 765 nm. Results were expressed as mg gallic acid equivalents per 100 g sample (mg GAE/100 g).

Browning Intensity – Measured following Ajandouz et al.¹⁵. Sap was diluted 1:25 w/v, centrifuged at 1006 g for 15 minutes, and absorbance measured at 420 nm.

DPPH Radical Scavenging Activity – Measured according to Payet et al.¹⁴. A 280 µL solution of 0.1 mM DPPH in methanol was mixed with 20 µL of sample or blank, incubated 30 minutes at room temperature, and absorbance measured at 515 nm.

The antioxidant activity was evaluated as a percentage of the radical scavenging activity (RSA) using the following equation:

RSA (%) = (Ao-As)/Ao x 100 ……………………………………………………….. (1)

where Ao is absorbance of the blank and As is absorbance of the sample at 515 nm after 30 minutes.

Chelating Activity

The chelating ability of sap samples toward Fe²⁺ ions was evaluated following the method of Kim¹⁶. One gram of sap sample was diluted fivefold and filtered to obtain a sap solution. Then, 100 μL of the sap solution was mixed with 600 μL of distilled water and 100 μL of 0.2 mM FeCl₂•4H₂O, and the mixture was allowed to stand at room temperature for 30 s. A control was prepared by replacing the sap sample with 100 μL of distilled water. Subsequently, 200 μL of 1 mM ferrozine was added to the reaction mixture, and the color change was monitored at 562 nm using a UV-1900 UV-VIS spectrophotometer (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) after 10 min at room temperature. Chelating activity was calculated using the equation:

Chelation activity

where A0 is the absorbance of the control, and As is the absorbance of the sample after 10 min of incubation.

Spectroscopic Analysis

Sugar solutions (25 mg/mL) were prepared by dissolving 250 mg of granulated coconut sugar in 10 mL of filtered demineralized water. The absorption spectra of the sugar solutions were recorded over a wavelength range of 200–700 nm using a UV-1900 UV-VIS spectrophotometer (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan)¹⁷.

Statistical Analysis

All data were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics 20 and are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Statistical significance was set at P<0.05P < 0.05P<0.05. The effect of varying lysine concentration was assessed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Duncan’s multiple range test at a significance level of P<0.05P < 0.05P<0.05.

RESULTS

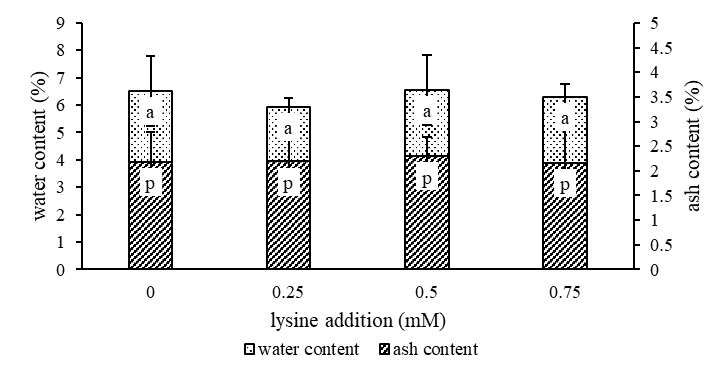

Water content and ash content

The water and ash content of granulated coconut sugar produced with different addition of lysine on coconut sap before heating is revealed in Figure 1. The addition of variation concentration of lysine were not significantly different on water content and ash content (p>0,05).

Note: Bars carrying same letters at the same parameter indicate means no significantly different at P>0.05

Fig 1. Water content and ash content of granulated coconut sugar. The results are representative of one independent experiments and values are expressed as mean ± SD from six experiments.

Reducing sugar, total sugar and sucrose content: The reducing sugar, total sugar and sucrose content of granulated coconut sugar produced with different addition of lysine on coconut sap before heating is depicted in Figure 2. The addition of variation concentration of lysine were not significantly different on reducing sugar, total sugar and sucrose content (p>0,05).

Note: Bars carrying same letters at the same parameter indicate means no significantly different at P>0.05

Fig 2. Reducing sugar, total sugar and sucrose content of granulated coconut sugar. The results are representative of one independent experiments and values are expressed as mean ± SD from six experiments.

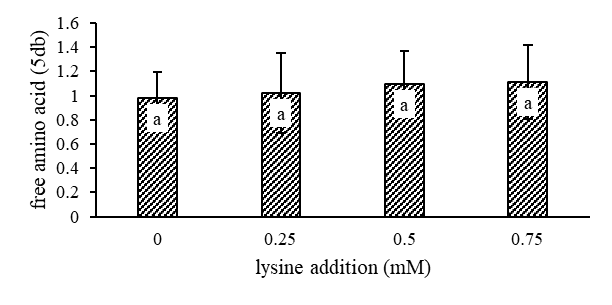

Total free amino acid: The free amino acid content of granulated coconut sugar produced with different addition of lysine on coconut sap before heating is showed in Figure 3. The addition of variation concentration of lysine were not significantly different on free amino acid content (p>0.05).

Note: Bars carrying same letters at the same parameter indicate means no significantly different at P>0.05

Fig 3. Free amino acid content of granulated coconut sugar. The results are representative of one independent experiments and values are expressed as mean ± SD from six experiments.

Total phenolic content and browning intensity: Total phenolic and browning intensity of granulated coconut sugar added with variation concentration of lysine on sap before heating is revealed in Figure 4.

Note: Bars carrying different letters at the same parameter indicate means significantly different (P<0.05)

Fig 4. Total phenolic content and browning intensity of granulated coconut sugar. The results are representative of one independent experiments and values are expressed as mean ± SD from six experiments.

Radical scavenging activity and chelating activity: The radical scavenging activity (RSA) and chelating activity of granulated coconut sugar added with variation concentration of lysine on sap before heating is depicted in Figure 5.

Note: Bars carrying different letters at the same parameter indicate means significantly different (P<0.05)

Fig 5. Radical scavenging activity and chelating activity of granulated coconut sugar. The results are representative of one independent experiments and values are expressed as mean ± SD from six experiments.

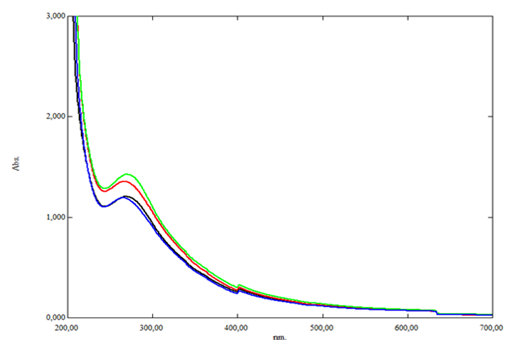

Spectroscopic Analysis. The absorption spectra of granulated coconut sugar added with variation concentration of lysine on sap before heating were recorded at Figure 6.

Fig 6. Absorption spectra of 25 mg/mL granulated coconut sugar produced added with 0 (black line); 0.25 (red line); 0.5 (blue line) and 0.75 mM (green line) lysine on sap before heating process line).

DISCUSSION

The addition of varying concentrations of lysine to coconut sap prior to the heating process did not significantly affect the chemical properties of the resulting granulated coconut sugar, including water content, ash content, sugar content (reducing sugar, total sugar, sucrose), and free amino acid content. Water and ash contents ranged from 5.94–6.57% and 2.17–2.30%, respectively. Reducing sugar, total sugar, and sucrose contents in the lysine-supplemented sugar ranged from 2.93–3.07% db, 90.21–94.37% db, and 87.24–94.37% db, respectively. Free amino acid content remained consistent across all samples, ranging from 0.98–1.11% db.

Total phenolic content of granulated coconut sugar with different lysine concentrations added before heating did not differ significantly, ranging from 0.94–1.22% db. In contrast, browning intensity was significantly affected by lysine addition. Increasing lysine concentration led to a more intense brown color, with 0.5 mM lysine producing the highest browning intensity. Higher lysine concentrations beyond this did not further increase browning, which is likely due to the Maillard reaction.

Coconut sap, the raw material for granulated coconut sugar, is rich in nutrients such as reducing sugars and amino acids, which undergo the carbonyl–amino reaction—the initial stage of the Maillard reaction. The neutral to alkaline pH of coconut sap facilitates the formation of reactive C2 and C3 sugar degradation fragments. These degradation products subsequently polymerize and bind with amino compounds, forming brown-colored melanoidin.

The radical scavenging activity (RSA) of granulated coconut sugar from sap supplemented with 0.5 mM lysine was significantly higher (73.96%) than sugar without lysine (67.45%). The RSA of a 10% sugar solution with 0.5 mM lysine was comparable to 100 ppm BHT (74.95%). Lysine, with its polar charged side chain, may enhance the Maillard reaction by providing nitrogen atoms. Its two reactive amino groups, including the ɛ-amino group, contribute to Maillard reaction products (MRPs), which possess antioxidant properties. For example, MRPs from a lactose-lysine model system heated at 100 ºC for 8.5 minutes demonstrated 50% RSA.

Chelating activity was highest in sugar produced with 0.25 mM lysine (7.01%), though this is considerably lower than the activity of 20 ppm EDTA (61.79%). Chelating activity likely arises from melanoidin, formed in the final stage of the Maillard reaction. MRPs are known to exhibit metal-chelating properties, which play a key role in antioxidant mechanisms. Melanoidin contains anionic compounds capable of chelating transition metals, preventing oxidation.

Granulated coconut sugar exhibited two absorption maxima: 264.5–268.5 nm and 401.5 nm. The first range corresponds to proteins, sucrose, reducing sugars, and MRPs such as reductones, while 401.5 nm is specific for melanoidin. Across all lysine concentrations, sugar was dominated by compounds absorbing at 264.5–268.5 nm (absorbance 1.193–1.426), compared to melanoidin at 401.5 nm (absorbance 0.287–0.303).

CONCLUSION

Varying lysine concentrations had no significant effect on water content, ash content, reducing sugar, total sugar, sucrose, free amino acid, or total phenolic content of granulated coconut sugar. However, lysine addition significantly influenced browning intensity, RSA, and chelating activity. Sugar with 0.5 mM lysine showed the highest DPPH radical scavenging activity, while 0.25 mM lysine produced sugar with the highest chelating activity (7.01%). Across all samples, compounds absorbing at 264.5–268.5 nm—proteins, reducing sugars, sucrose, and MRPs such as reductones—dominated over melanoidin.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

All authors in this article declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- Borse, B.B.; Rao, L.J.M.; Ramalakshmi, K.; Raghavan, B. Antioxidant properties of caramelized sugars. Food Chem. 2007, 101, 877–880.

- Hariharan, B.; Singaravadivel, K.; Alagusundaram, K. Effect of amino acid addition on sugar browning. J. Nutr. Food Sci. 2014, 4(5), 1–5.

- Asikin, Y.; Kamiya, A.; Mizu, M.; Takara, K.; Tamaki, H.; Wada, K. Maillard reaction products in sugar processing. Food Chem. 2014, 149, 170–177.

- Nagai, T.; Kai, N.; Tanoue, Y.; Suzuki, N. Browning and antioxidant activity in sugar products. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 55(2), 586–597.

- Carciochi, R.A.; Dimitrov, K.; Galván D´Alessandro, L. Influence of amino acids on sugar browning and antioxidant activity. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 53, 1–9.

- Ho, C.W.; Wan Aida, W.M.; Maskat, M.Y.; Osman, H. Chemical composition and antioxidant activity of sugars. Pak. J. Biol. Sci. 2008, 11(7), 989–995.

- Wijewickreme, A.N.; Krejpcio, Z.; Kitts, D.D. Effect of amino acids on radical scavenging activity of sugars. J. Food Sci. 1999, 64(3), 457–461.

- Kim, J.S. Influence of Maillard reaction on antioxidant properties of sugar. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2013, 22(1), 39–46.

- Yan, F.; Yu, X.; Jing, Y. Browning intensity and antioxidant activity in sugar with lysine addition. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 55(2), 712–720.

- Karseno; Erminawati; Tri Yanto; Setyowati, R.; Haryanti, P. Chemical and antioxidant characterization of coconut sugar. Food Res. 2018, 2(1), 32–38.

- AOAC. Official Methods of Analysis, 15th ed.; Helrich, K., Ed.; Association of Official Analytical Chemists: Virginia, 1990; Vol. 1.

- Miller, G.L. Use of dinitrosalicylic acid for sugar determination. Anal. Chem. 1959, 31(3), 426–428.

- Yao, L.; Liu, X.; Jiang, Y.; Caffin, N.; D’Arcy, B.; Singanusong, R.; Datta, N.; Xu, Y. Phenolic compounds and antioxidant activity in sugar. Food Chem. 2006, 94, 115–122.

- Payet, B.P.; Sing, A.S.C.; Smadja, J. Antioxidant and Maillard reaction products in processed foods. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2005, 53, 10074–10079.

- Ajandouz, E.H.; Tchiakpe, L.S.; Ore, F.D.; Benajiba, A.; Puigserver, A. Kinetics of Maillard reaction in sugar-amino acid systems. J. Food Sci. 2001, 66(7), 926–931.

- Bekedam, E.K.; Schols, H.A.; Van Boekel, M.A.J.S.; Smit, G. Formation of melanoidins in food systems. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2006, 54, 7658–7666.

- Delgado-Andrade, C.; Rufian-Henares, J. Assessing the Generation and Bioactivity of Neo-Formed Compounds in Thermally Treated Food; Editorial Atrio: Granada, 2009.

- Eskin, N.A.M.; Shahidi, F. Biochemistry of Foods, 3rd ed.; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2013.

- Morales, F.J.; Jimenez-Perez, S. Formation and activity of Maillard reaction products in foods. Food Chem. 2001, 72, 119–125.

- Delgado-Andrade, C.; Seiquer, I.; Nieto, R.; Navarro, M.P. Antioxidant and chelating activity of Maillard reaction products. Food Chem. 2004, 87, 329–337.

- Jing, H.; Kitts, D.D. Radical scavenging activity of Maillard reaction products. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2004, 429, 154–163.

- Verzelloni, E.; Tagliazucchi, D.; Conte, A. Melanoidin structure and antioxidant properties. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2010, 48, 2097–2102.

- Daglia, M.; Papetti, A.; Aceti, C.; Sordelli, B.; Gregotti, C.; Gazzani, G. Metal chelation by melanoidins in food systems. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2008, 56, 11653–11660.

- Rufian-Henares, J.A.; De La Cueva, S.P. Antioxidant and chelating properties of Maillard reaction products. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2009, 57, 432–438.

- Tagliazucchi, D.; Verzelloni, E.; Conte, A. Characterization of melanoidins from processed sugars. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2010, 58(4), 2513–2519.